IntroductionW.R. Winspear was a pivotal figure in the radical labour movement of the 1880s and 1890s. His newspaper, The Radical, later called The Australian Radical, has been called the first regular socialist newspaper in Australia. He was also active in the socialist movement, and anti-conscription campaigns of the first World War. In 1936 he was honoured for his role in the anti-conscription campaign during the First World War. He died at the age of 84 in 1945.This essay examines how several historians have interpreted Winspear's politics. Bob James has gone back to primary sources to question Winspear's politics and motivations. His research clears the path for a fuller biographical appraisal of Winspear and his contribution to the radical tradition in Australia.

Takver, February 2000

|

Available Writings of W.R. Winspear

Only a full-blown biography could attempt to provide all the detail, all the ups and downs in the life of William Robert Winspear. This pamphlet will not claim to be a comprehensive account of the major peaks and troughs. Too much piecing together of the scattered fragments of an idealist's existence still remains to be done even for that.

In this partial tribute to the editor of what has been called 'the first regular socialist paper in Australia' I have focused on his politics and on the way historians have so far referred to his politics, in order to clear some of the briars on the path to that necessary and appropriate fuller appraisal.

For if we bring together references to Winspear in the so-called sympathetic literature we find anomalies so large and so strange as must force us to seriously question what has passed for labor history so far in Australia. The flaw is not merely in the eyes of individual historians, there is also an accumulated sloppiness, superficiality and, more importantly, a bye and large general attempt to gloss over and bury basic truths. Supposedly in the interests of bolstering the chances of radical social change against the conservatives, some historians have done great damage to their own credibility and to the transmission of the anti- establishment message by pretending among other things that only the centralised, hierarchical form of socialism is valid, indeed the only one that existed in substantial form in Australia. This latter claim is factually wrong, and shows, if it is seriously believed, a combination of wishful thinking and poor methodology, but the whole approach reduces to the point of absurdity the lives of the people its practitioners claim to be remembering. It does this by ignoring the context which is much more diverse and complex than the glossy version implies.

If we start with the account provided by G. D. H. Cole, a respected British author and historian the beginnings of the problem, the sloppiness, begins to emerge.

Then in 1887, 'a group of immigrants from Great Britain founded at Sydney the Australian Socialist league. There were only six of them; but they started a journal, The Australial Radical. Then they quarreled. The proprietor of The Radical became an anarchist and the league repudiated him and started a new journal, The Socialist. Neither had a long life.

- G. Cole, History of Socialist Thought, Vol 3, pt 2, p 869.

Cole was here writing about a very minor series of items in his broader canvas which was concerned with the other side of the world, nevertheless his 'research' was probably based on letters written to him some years afterwards. Certainly within the ASL which began in Sydney in 1887 there was a quarrel between Winspear, the proprietor of The Radical and others over his advocacy of anarchism. But they weren't all immigrants from Britain, the ASL didn't start The Radical and neither did they start The Socialist.

This is just one example. A number of Australian historians writing in the 60's and 70's didn't get much closer to the real ASL.

But the overwhelming sense which has lingered from the Cole account, corrected or not, has been that anarchists and socialists, necessarily do not get on and must separate. Again Cole is only one example. But what can one conclude from putting this account alongside the claim that The Radical was the first regular socialist paper in Australia and/or next to Nairn's claim in Civilising Capitalism that Winspear was 'an anarcho-socialist'.

The usual spectrum of union and radical opinion was reflected at the [1892 PIP] conference, single taxers and the rest, including an anarcho-socialist, W. R. Winspear who was opposed to trade-unions; but they were all members of, labor leagues and the changes they made to the [PIP] platform were chiefly trade union demands.

- B. Nairn, Civilising Capitalism, ANUP, 1973.

One could at least fairly deduce from the two quotes that Winspear's anarchism was of importance to him. Nairn is no radical and we might deduce from his own politics and from the fact that this is his only reference to Winspear that the 'anarcho- socialist' label is simply a mistake based on ignorance and the sort of thinking that has left radicals and minorities of many kinds out of 'official' history.

Despite the ready availability of source materials to those prepared to look and the significance of the stigmatisation of anarchism to the loss of radical vigour, many, certainly the older Australian political historians give the impression of being politically illiterate and historically blind. Overall, a similar myopia prevails here as in other historiographies, namely. theories of self-management, descriptions of rank-and-file struggles and attempted solutions, and studies of institutional or status-quo repression have all been neglected.

There has been a considerable resurgence of academic interest in anarchism in the Northern Hemisphere in the past 10 to 15 years but the mistakes of the past have by no means all been rectified. It is still possible to find, among so-called 'left-leaning' accounts, State- terror and coercion described in far less emotive terms than that of the anti-authoritarians. It is still possible to find so-called social analysts confusing wealth with power, the most irritating being that of Marxist historians and anarcho- capitalists. Chomsky points out that it is still the norm to find both leninist and liberal ideology justifying the selective reporting and distorting of facts in order to denigrate "mass movements and ... social change that escapes the control of privileged elites".

The attempt by people who see themselves as Marxists to portray anarchism and decentralised socialism as an irrelevance must be seen as just another blow in the struggle between Marx and Bakunin, now continued posthumously. It is a struggle with elements of pettiness but it is also of central importance to everything these writers referred to are considering - no less than a fight for the body and blood of socialism (not the corpse as some might have it). The question of the need or otherwise to centralise decision-making power, before, during and after a revolutionary event, remains the question.

In cooler terms, the struggle is over the definition of socialism as legitimating factor, the property deeds of the revolution and just as the debate went on in the times described by historians, so it continues in 'the history' itself.

Historians writing today, in failing to comprehend the significance of this for themselves, have failed to suitably assess their sources and have, at least when it has suited them, taken the accounts provided by past writers literally. Thus, at its extreme in the present context, anti-anarchist historians have used definitions of anarchism by non-anarchists to explain anarchism and thus to justify their discounting of anarchism. This is like misogynists using male definitions of the female experience to justify misogyny.

This sort of approach is particularly exposed when applied to the likes of Winspear who was a key player in the actual debates between the centralised and the decentralised views.

When he, his newly-married wife Alice and her father began producing what he incidentally also called a socialist paper in March 1887, Winspear espoused a list of demands ranging from Australia for Australians, neutrality of Australia, adult suffrage, payment of MP's, direct taxation, colonial federation and local government to election of an Australian Governor or President.

While he held that 'Government as it is at present is simply a comedy which is not even well played' he did not in the beginning agree with the view of the editors of 'Honesty' the Melbourne Anarchist Club paper begun the same year that 'all Government is evil and that because present governments are bad, a good Government is impossible'.

The Australian Socialist league had held its first meeting in May 1887 but it was not until after it had a second birth in August that it and The Radical staff found one another and joined forces. The ASL's first manifesto was almost exactly the same as that for the Melbourne Anarchist Club which had begun the year before. One reason for the close similarity was that David Andrade and his brother William Andrade were founder members of the MAC, and William had come to Sydney in 1886 and had begun looking around for people to join him in producing a Sydney Anarchist Club. Discussions produced the ASL which was undoubtedly more anarchist than centralist in its early years, but the one important difference between the two manifestoes shows the beginnings of a movement away from the anarchism of David Andrade, the dominant theoretician of the time. His anarchism was derived from Proudhon via Benjamin Tucker, while that prevalent in the ASL tended towards the communist form. However when Winspear debated these matters he succumbed to the Andradean-version, so that when the ASL group in Sydney repudiated him it was not because of a socialist-anarchist hostility but because of a collectivist-co-operativist split.

The MAC split at about the same time and also between the Andradeans and a more communist-oriented anarchism brought forward by Jack Andrews who became, incidentally, one of the founder members of a Melbourne branch of the ASL. Despite the difference in their views or perhaps because of it, Andrews and Winspear provide extremely interesting material in the pages of the Australian Radical during 1888-1889 as they debate with each other and some others such issues as revolutionary violence, co-operatives, contraception, credit notes, education and of course socialism.

During a strike by coal-miners in the Newcastle area, a strike which produced the ominous sign of military transporting cannon by railway flat-tops to intimidate mining camps, Winspear produced a substantial pamphlet called: The Crisis: An Open Letter to the Miners of Northumberland. After speaking of the current struggle he went on to argue that the miners set aside some of their wage each week to establish 'distributive' stores which could provide food, clothing and furniture at reduced rates because of the cutting out of 'middlemen and speculators'. Such co-operative outlets would be ultimately furnished with stock from co-operatively-run mines, farms, banks, newspapers, etc, etc, until, Winspear envisaged, Co-operative Villages would spring up all over the country spreading 'the glorious gospel of Universal Co-operation, Fraternity or Socialism'.

This was published in August, 1888. On 11 May, 1889, the paper reported that 'Co-operative distributive stores are now doing good business in Hamilton, Wallsend, Lambton, Stockton, Islington, Burwood, and others are said to be in process of formation in other places'.

At this point the ASL and The Radical are parting company even though each has less chance of survival on its own. McNamara and a rump of the ASL claim The Radical stands for values all true socialists oppose. A curious though perhaps expectable claim.

Verity Burgmannn, whose work I have some respect for, then makes 2 statements about the resulting 1890 situation, just one page apart which, if they were noticed and put together by contemporary readers must cause great consternation:

p. 169:- He [Winspear was determined he] would lay the foundation for a new idea - the supremacy of the Individual. The methods it has adopted are impartial and non-partizan criticism, fairplay to all, and reliance upon the survival of the fittest. p. 170:- In the years since the Labor Party's formation, however, socialist ideas and organisations had developed considerably, and he was able to find in the Australian Socialist Party [in 1910] the 'true socialist party he had longed for in 1890'.

I tend to think that these seemingly opposed statements overlap, but without explanation from Burgmannn and without indication that she has looked at the necessary anarchist materials, one wonders how the author sees them as co-existing. Jack Andrews developed the idea of a positive relationship between communism and individualism around 1889, and may well have influenced Winspear away from co-operatives. But Andrews would not have been at home in the ASP, I suspect.

Here, my point is simply that these ideas are far too basic, too important and too contentious to be simply stated and left.

The ASL as one might expect, was initially opposed to parliamentary politics but had been moved by 1891 to a more reformist position under pressure from an influx of careerists and opportunists who saw a chance for self-promotion in the formation of a labor party. The process of stigmatisation which followed the framing of Chicago anarchists, key labor leaders after the 1886 Haymarket explosion was also significant in undermining the anti-Parliamentary position. In combination, the worldwide repression directed at all labor radicals after May 1886 especially forced agitators to reconsider the more respectable, thus safer, parliamentary road to reform. In July 1891 the Sydney ASL purged itself of all self-avowed anarchists in the same resolution that excluded persons with a criminal record from its platforms and stopped ASL agitations on behalf of the unemployed. These measures were part of the larger realignment of labor forces with a trade-union movement that was allowed to continue only if it became the handmaiden of a parliamentary party. In the debate over tactics the direct actionists lost and the pragmatists won. Thus the centralisers necessarily achieved hegemony over the decentralisers. The struggle continued of course. Rose Summerfield, an anarchist, established a further branch of the ASL in 1892 in Broken Hill.

Both Winspear's public and private life were having to endure great changes. He topped the poll for Councillor to West Ward on Hamilton Council (Newcastle) in February 1891 and over the next 12 months attempted to influence local policy towards social welfare issues. There is almost no detail available of discussions within Council but Winspear appears to have made few waves. He then simply ceases to be a Councillor in 1892, perhaps to concentrate on his printing press as revenue raiser in an increasingly hostile environment.

The family, about the mid-1890's, moved to Sydney where apart from political work about which very little is known, he engaged in some doubtful business deals, became more desperate, tried burglary, was caught and jailed for 18 months. Alice, now burdened by a number of small children, unable to follow her budding writing career, or any other paid employment, perceived her one way out of poverty and starvation would also produce an improved situation for her children. She hanged herself.

In another paper sometimes produced in Newcastle, The People and Collectivist, some of this tragedy is recounted by Harry Holland who later became Labor Party leader in New Zealand. Alongside the article on Mrs Winspear the paper has some definitions of Socialism, none of which, I believe Mr Winspear would have opposed. Nevertheless, 'Otus' ie Holland says in the article:

Bob (Winspear) was always opposed to the socialists - he was a pronounced individualist ...

Even in responding to the distress of a 'respected' friend, Holland continues the struggle over the definition -'socialism' can only be of the kind he favors. Holland himself ran foul of the dog-in-the-manger attitudes a few years later when told by the ASL executive that The People was spending too much space on trade-union activities.

There are many gaps in the Winspear story. As his family has increased rapidly (his views about contraception appear to have been unformed, while those of his wife are equally unknown) emphasising the need for survival strategies, so with Alice's death and his need to re-establish himself after jail, even his efforts on behalf of 'labor' electoral candidates which Holland applauded up to 1898, appear to cease.

He re-emerges publicly in 1910. From this time when his material shows up in the International Socialist weekly paper until September 1916 when he resigns from the dual posts of treasurer and editor he worked long and hard, in many forms, for the Australian Socialist Party and the 'true' socialism he claimed to have been searching for from 1890. There is no doubt however that his views have changed and that his class-based rhetoric from 1910 bears little resemblance to his ideas about voluntary cooperation and survival of the fittest 20 years earlier. How much in substance they had changed is, I believe, still open to discussion however.

These are of course the years of the IWW and agitation for One Big Union and inevitably the same arguments about the definitions broke out as had split the ASL in 1888-89, and many groups since.

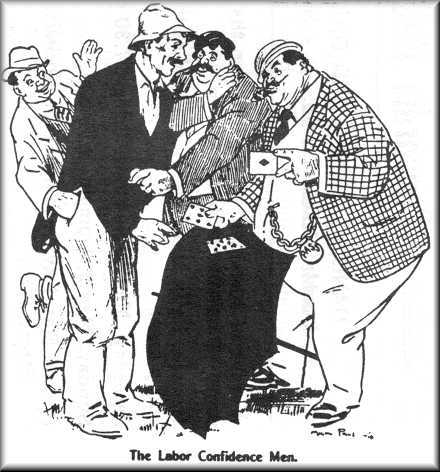

Cartoon from International Socialist. Feb 7, 1914 |

The IWW in the United States split into a Detroit-based group and a Chicago-based group, and while there is much loose usage of terms and much personal abuse obscuring the issues, it can be generally said that the Chicago group was more attuned to a decentralised approach than the other.

In Australia, splits, not as clearly geographically based, bubbled along producing unfortunate acrimony. Ian Turner wrote:

On the revolutionary political front, the IWW Club had fallen away by mid-1913 ... the SLP was complaining of 'apathy and indifference', . . . the membership of the VSP was down ... and the desperate efforts of the political socialists to meet the IWW challenge by uniting their declining strengths all foundered on sectarian bitterness.Meanwhile, the IWW (Chicago-style) flourished.

I. Turner, Industrial Labour and Politics, p. 66.

As editor Winspear was nominally most responsible for the anti-anarchist tone which developed in the I.S. paper.

There appear to be many elements in the debates. There is argument over the relative placing of unions viz-a-viz 'the Party', whether to have a Party, which candidates to support, whether to indulge in 'direct action', whether to strike now or later, and such seemingly unrelated areas as eugenics. Those people I'm grouping together as decentralisers are variously labelled by the I.S. as 'anarchist', 'direct action IWW', 'anti-political IWW' 'anti- socialist IWW' and 'syndicalist IWW'. Even within this paper though the traffic is not all one way.

No doubt some elements of this decentralised group, then as now, were a disorganised, destructive burden on their colleagues but there were other decentralisers whose worth simply could not be trivialised or denigrated. Some of the best cartoons used are by Robert Minor, a North American anarchist.

Particularly interesting in hindsight is the following quote the I.S. says comes from the Sydney Worker of 13 March 1913:

The suffragettes are once more demonstrating that the only way for the 'under' people of England to obtain political rights is by the continued destruction of property.

This is by (later Dame) Mary Gilmore. Winspear had to editorially acknowledge developments in WA in 1915 which apparently caused him to ban items of news from the Perth group. These developments included decisions by Annie Westbrook and Monty Miller, both founder members, to leave the WASP.

... Monty Miller has always stood for anarchism and should never have been in any Socialist Party. If Mrs Westbrook accepts Miller as a guide, philosopher and friend she should have been with him outside of any politico-industrial party. We congratulate our anti-Socialist fellow-workers on the acquisitions to their ranks.(I.S., 17 April, 1915, p.3)

Intriguingly, Eric Fry in his chapter on Miller in Rebels and Radicals, "Australian Worker" more fairly describes Miller as a socialist, but so that readers won't get the 'wrong' impression, simultaneously separates him from the anarchists of the MAC, of which he had been a member, back in the 1880's. Fry locates Miller within the anti-(Parliamentary) politics, direct-action IWW, which, in Fry's version, is the only IWW and thus suffers no splits and debates not at all the different paths to the OBU.

This juggling act, of course, allows Fry to gloss over Miller's relations with other socialist groupings such as the A.S.P. and to remark no incongruity at the use made of Miller by many socialist organisers in the 1916-1920 struggles, during which Miller himself was twice jailed for anti-conscription, anti-militarist activities.

W.R. Winspear, 1919 approx. |

Did Winspear resign only because of illness, or because of raids from the security police which occurred just as he was leaving the I.S.? Was there an ideological component?

His fables and his editorials when he succeeded Holland had been especially concerned with the dangers of patriotism and it is probable that he will be longest remembered for his scathing attacks on 'the leprosy of militarism' culminating in his poem The Blood Vote introduced into the conscription struggle just as he retired from active involvement in the I.S. He had been equally strongly opposed, back in 1888, to revolutionary violence when debating with Jack Andrews in The Radical.

His longer pamphlet Economic Warfare (1915) indicated that since 1890 he had certainly taken Marx on board but he was still exhorting his readers to freedom through self-activity, not emphasising co-ops as he had been, but emphasising workers' control of industry. While asserting economic production the dynamism for history and social change and the class war is the central motif. But in setting out his ideas about the way forward there is very little Marx.

He has 3 key ideas:

- (1) the propaganda so far has been haphazard and too theoretical;

- (2) State socialism must be opposed in every way by every means and

- (3) Party government must be overthrown and replaced with industrial self-government.

'So far our speakers and writers have fired at random taking no account of the economic conditions that so largely govern the views of those they seek to win'.

He argues for a high level of specialisation in both the content of propaganda and in the selection of people for particular tasks. Speakers should bone their arguments to their audiences and be relevant not theoretical. The specialisation should extend to creating handy reference books on strikes, and to sending people to Parliament just to harass the members of parties and to expose their failings. A third task in Parliament of equal significance would be the stalling of attempts at bailing out small businesses or particular industries with schemes of nationalisation as the class war intensified. No government is suited to be an employer and labor Governments are no exception in his argument:

Our railways and post office are excellent examples of the futility of endeavouring to gain freedom through governmental schemes of nationalisation ... Government was founded before the age of machine production was set in and it is unsuitable as a means of administering the resulting new organisation.

He appears to be critical of his colleagues as well as the know nothings and finishes: "These ideas may seem to require too high a level of organisation, but so far we've all been too haphazard to achieve 'the industrial republic we dream of'.

It's too early to know what to make of W. R. Winspear in toto. What we can be sure of are two things:- firstly, a certainty that W. R. Winspear should be honored for his long-term commitment to social change. He, his paper and his various projects are all important parts of our history. Secondly, this story, fragmentary though it is, poses questions which the Hunter Labor History Society and similar bodies should not ignore. For not only do we need to ask questions about the retrieval and maintenance of 'labor' history, but about the standards we're prepared to accept in its presentation and publicising. In particular I can no longer accept the notion of history as being about grand flows, or great clashes between generalised concepts eg class war, or Communism V the West, or equally simplistic lies. History is a result of people's actions and thoughts, fears and attempts to survive. History as it is transmitted must reflect diversity and complexity, tangles of emotions, plans and false starts, failure, disillusion and compromise, along with the glittering prizes, if any.