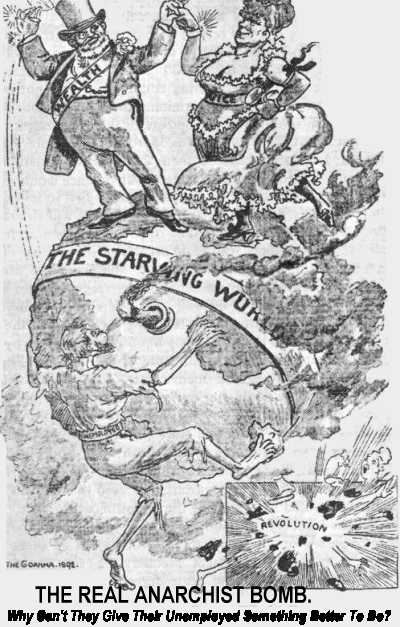

Civilisation of our day very much resembles a group of selfish children scrambling for sweets at a school picnic. The inventive genius of mechanical man has far outstripped his knowledge and love of equitable principles, so that today we see untold wealth on every hand, increasing facilities for the creation of more wealth, every where a promise of future abundance and plenty for all, and a mad endeavour on the part of human beings to monopolise as much as possible to the exclusion of their fellows. In the grand march of industrialism men are constantly being electrified and dazzled by some new method of making the fruits of labor, the bounties of nature descend in grateful showers into the top of society, and like short-sighted, selfish children they elbow and push each other in order to monopolise as much as possible of the results. The old barbaric selfishness which led them to believe that might is the only right, still clouds their reason, and prevents thern from seeing that higher selfishness which prompts the civilised ego to act socially even for its own best interests, and so they continue to act unsocially and prey upon each other. Growing abundance opens our eyes but slowly, and though our storehouses are creaking full of food and clothing men still continue to scramble as though a certain famine stared them in the face. Their love of conquest and distinctions founded thereon, still sway them, and though within what they call their own country they may not proceed to rob their neighbours accompanied by hosts of hired cut-throats, they nevertheless rob them still. As of old man spends much of his time in concocting schemes for the robbery of his fellows, the sources of wealth being his favourite means. No doubt, if one half the cuteness and energy at present displayed in monopolising and checking production, were thrown into aiding production, the world would be one vast paradise. Real good men never grow rich, those who become distinguished by great wealth, are for the most part the warlike, the avaricious and least civilised of all humankind - men who make politics a business, a means of exploitation, and of securing privilege and distinction. Low cunning tells them that the display of great wealth in pomp, ceremony and equipage, will secure them the homage of the unthinking, so they plot always to amass wealth, to create inequality, to lord it over their fellows and impose upon them as influential and great members of society. Observe the highest officials in any country, the governors, premiers and politicians, say of Australia. See how their little minds are excited by a military display, a jubilee meeting, a horse race or boat race, a pugilistic encounter or a vote of condolence to her majesty. These are great events to them, for they enable them to 'come out' in style and show off to advantage.

Militancy, conquest, love of distinctions and inequality have no doubt contributed towards civilisation and progress. Perhaps a state of inequality is necessary, in order that we may pass though it and be prepared for the goal of civilisation - liberty and equality. Perhaps the best security we can have for the future equality of conditions will be a general persuasion of the inequity of accumulation, monopolies and inequalities founded thereon, and a knowledge of the uselessness of wealth in the purchase of happiness. But this persuasion could not be established in a savage state; nor could it be maintained if we fell back to barbarism. The spectacle of inequality and distinction first excited the grossness of barbarians to persevering exertion, which first gave the reality, and the sense of that leisure which has served the purposes of literature and art. But though militancy, love of conquest, and aristocratic distinction may have been necessary as a prelude to civilisation, they are not necessary to its support. We may take away the scaffolding when the structure is complete.

The problem of the future then, already presents itself to us. We know how man has progressed in the past; how will he progress in the future? War has assisted to bring us so far, will it be necessary to use it still further? Perhaps no revolutions in the past have been accomplished without bloodshed; will the revolution of the future be also a bloody one? Will we be able, without the shedding of blood, to revolutionise the present system, so that the most civilised will fill the positions of trust and the laborer be left in the enjoyment of the fruits of his labor? Will we be able to rid ourselves of the warriors and robbers without one last hand-to-hand encounter with them? These are questions which many are asking, and which all should ask themselves.

If the robbery of labor, which we may call the robbery of today, was a simple march upon the laborers' possessions and an open attack upon the produce of his labor and an attempt to carry off his productions by sheer force of arms, we might easily conclude that there would at an early date be a tremendous fight to a finish, for such a robbery would be easily comprehended by even the militant type of man. But the day of such a robbery is gone. It was expelled by militant man years ago. The robbery and injustice of today is involved, is intricate, and so hard to understand and hidden from view, that it is safe to say that few really do understand it. The militant type of man can never understand it, and as man progresses still further in the direction of industrailism his whole nature will be changed and his inclination to redress his wrongs by force of arms modified. Thus he must progress in philosophical study ere he will understand the nature of the evils to be removed is evident when we look around and see everywhere the victims and sufferers from these evils prepared to defend them and doing their best to perpetuate them. The average worker must increase his knowledge of what inequality and government are before he will be persuaded of their inequity, and be prepared to dwell under conditions of liberty and equality. Hence we are inclined to believe that any resort to arms will not bring the era of justice, that on the contrary a resort to arms will tend to check the progress of economic knowledge and perpetuate the reign of barbarism.

It is said that the unfortunate laborer, who, with unrequited labor, finds himself incapable adequately to feed and clothe his family, has a sense of injustice rankling in his heart which in time becomes unbearable. Now by observing this man and his class we may see what form his resentment is likely to take. On the Prince of Wales's Estate in Cornwall, the workers are left by the Prince to support their families on a shilling a day, while the prince robs them of £76,000 a year in royalties. Yet this same prince received quite an ovation the other day, on his estate, from these poor people whom he robs, and whom we may suppose have a feeling of injustice rankling in their hearts. A radical MP who refused to stand up at a banquet when the toast of the prince was being drunk, got himself hooted and hissed, and had to stand up to save himself from being thrown out of the window, yet the radical MP was more their friend than the prince was. In their case, the feeling of injustice, if they had it, was not allied with a knowledge of what the injustice was, hence they were likely to throw the wrong man out of the window. In Northumberland, NSW, the miners were so ground down by the landlords, capitalists and mineowners that the feeling of injustice prompted them to strike and look dangerous to their masters, the masters in their turn did everything they could to provoke a row in the way of persecution, by bringing them to court, coercing them with police, and military armed with gatling guns. When the strike ended and the men were virtually beaten, a general election came on and these same miners howled themselves hoarse in applause of the principles (!) the mineowners put before them and the protection they promised. Any opponent who wished to rake up old grievances was summarily silenced. The mineowners were voted into Parliament and into the municipal councils to make laws to remedy existing evils. Fancy a revolution by bloodshed taking place here. Their best friends would have been butchered no doubt, while the humbugs and imposters who parasitically fleeced them would have been hoisted into power. The writer has met men who came from Arnerica, and who maintain that Parsons threw the bomb at the Hay market meeting in Chicago, and that he and his comrades were well hanged and out of the road, because they irritated the capitalists and made them hard with the men who worked for them. Yet we at this distance know how erroneous this is. But it serves to show that the feeling of injustice unless accompanied by philosophic insight into the nature of the injustice leads directly to nothing. If a revolution took place today or within the next few years, many of the best socialists would be killed off by mistake while the humbugs and imposters would be carefully preserved. On the morrow of the revolution we would want to go peacefully to work and would desire to live in liberty and equality, without government or authority, but it is safe to say that new governments would be formed and new standards erected and robbery and inequality would commence afresh, from the simple fact that mankind do not yet possess a knowledge of the evils to be wiped out. Does it not then appear that we have all to lose by a resort to force, and all to gain by postponing it and relying upon reason and education to bring mankind to a knowledge of the evils of monopoly and privilege and a love of equality and liberty.

A bloody revolution is engendered by indignation against tyranny, yet is itself far more pregnant with tyranny. The tyranny which excites its indignation is not without its partisans; and the more sudden is the indignation excited and the fall of the oppressors, the deeper will be the resentment which fills the minds of the losing party. What is more unavoidable than that they should object to be dispossessed of their privdeges suddenly and violently? What is more natural than that they should feel attachment for the sentiments in which they were educated, and which only yesterday were the sentiments of the vast majority of men? If it is true that our own interests prevent us from clearly seeing arguments which tell against us, what is more natural than that they will be unable to see our reasons for the change? They have but remained at the point at which we all stood a few years ago and they are defending the opinions of a lifetime. Yet this is a crime which a bloody revolution watches with jealousy and punishes with severity. It would not tolerate the man who held to his principles and dared to vindicate them, yet such a man might not be the worst we could meet.

Revolution may be engendered by a horror of tyranny, yet its own tyranny is peculiarly aggravated. There is no period more at war with the existence of liberty. Government interferes with the communication of opinions, but such a period sees opinions doubly fettered. At other times men do not so much fear the consequences of free discussion, but during a period of turmoil and bloodshed the influence of a word is feared and the consequent slavery is complete. There never yet was a revolution accompanied by bloodshed in which a powerful vindication of what it was intended to abolish was permitted, or any species of argument which was not in harmony with the objects of the revolution. Anything which tends to check the flow of opinions, anything which tends to fetter men's minds and punish them for their views is to be deplored, yet this is characteristic of a period of such a revolution.

Numbers of men have the idea that it will be next to impossible to rid ourselves of our oppressors and prevent new ones from taking their places, unless we inflict memorable and severe retribution. But there will always be oppressors as long as there are individuals who will take sides with them and defend them. Thus we will have to terrify not only the tyrant but all those who take sides with him. We wish to make men free and the method we adopt is punishment. We say that government has encroached too much, yet we call into existence a machinery which enforces its will with ten times the rigour that it did. Before proceeding further, we may well ask whether we must enslave ourselves to make us free? and whether a display of terror is the readiest mode for making men wiser, fearless, equitable and independent?

Today improvement of mankind depends upon quiet speculation, but a fierce hand-to-hand conflict arrests enquiry and patient speculation. It drives humanity out of man and turns him into a beast, with military ardour in his breast and admiration only for such leading characteristics as bravery in battle, characteristics in which the Tasmanian Devil or the Game Cock are his superiors. The philosopher who preferred his study to the turmoil of war, during a bloody revolution would run great danger of being charged with cowardice or treachery and would very likely be hanged. Thoughtful people would be hourly under the strongest impressions of fear and hope, apprehension and desire, dejection and triumph, and with such a multitude of conflicting emotions, moral forces would exert but little sway, if any.

It is all very well to say that in any future revolution the revolters would be animated by the purest and tenderest motives, and would be ridding the earth as a matter of duty, of all tyrants and oppressors, in the hope that when once they were swept away the earth would see them no more. The purest and tenderest motives become very much tainted and corrupted when man has once shed the blood of his fellows, and as we may suppose the revolters will not be always wise and discriminating, huge blunders will be made, and real friends, valuable friends, will be slaughtered by mistake. We ought to be extremely careful of the lives of some men, whose usefulness may not be quite apparent to the mass, but during war the most valuable human beings are valued tightly and may have their career cut short through a mere madman's whim. Such a revolution would be decided by force, and not by discussion and expostulation. It would be a fight between two parties each persuaded of the justice of its cause, and would really be no settlement of the mutual animosities. The perpetration and the witnessing of the slaughter of the friends of both sides would generate a thousand fit passions in the breasts of those concerned. The perpetrator and the witnesses of murder become obdurate, inhuman and unrelenting. Those who lose their relations and friends are filled with indignation and revenge and come to such a state of feeling that they can rejoice at the most horrible cruelty perpetrated upon their foes. Distrust and ill feeling are transmitted from man to man and the ties which knit human society together are snapped asunder and destroyed. It would be impossible to think of a period more at war with liberty and justice than a period of forceful revolution.

Revolution by force is generally crude and premature, and is not the result of scientific investigation. There is a science of society capable of being understood, and the laws underlying human co-operation are explainable, but it is clearly the method of all science to be progressive. The science of astronomy made many steps and stages ere it was perfected as far as Newton perfected it. Biology progressed slowly till Darwin's time, and so it must be with sociology. The science of society is yet in its infancy. It is known and recognised by but few, just as the history of all sciences proves is the case with every new discovery.

It is given to but a very few to see the light at first, and if we are the few who see the light of the dawning social science, we should behave like true scientists, and appeal to the understanding of man by explaining our discovery. Any institutions we may build will be lasting only when we build them in accordance with the growing intelligence of humanity. We cannot force the new society into existence. It must grow. Politicians have long endeavoured to manufacture society, but it grows in its own way. Let us not fall into the error of the politicians. Let us rather devote ourselves to the task of showing the imperfections of political society, and rest assured that imperfect institutions cannot support themselves when they are generally condemned. When imperfect institutions are undermined by reason they decline and fall. Men feel their situation, and the restraints that once shackled them vanish like a deception. By the method of science the crisis is reached and passed, without the need of sword being lifted. The adversaries are too feeble and few to entertain the thought of resisting claims which are based on the universal sense of mankind. Does it not appear then, that our work is a work of education?

So long as we are allowed to reason upon theories and fight sophistry with truth we may look with tolerable assurance for the result but when reasoning is stopped and both sides arm themselves with sword and stratagem, error becomes organised and equipped in a way which was impossible before. Then amidst the barbarous rage of war it becomes very uncertain whether right or wrong will win, and if wrong wins as it sometimes does in war, the result will be a renewal of the chains of slavery, a new lease to tyranny.

"But", we may be told, "Ages may elapse before philosophic views of the evils of privilege and monopoly shall have spread so wide and be felt so deeply, as to cause man to banish these evils without violence and commotion. It is easy for the mere reasoner to sit in his closet and amuse himself with the beauty of the conception, but meantime men are perishing. Let us be up and doing, let us take the chances which war may throw in our way, for unless we do this, we may go off life's stage ere any benefit comes. Let us embrace a method which shall secure us a speedy deliverance, from evils too hateful to be endured."

In answer to this we may urge that to attempt to rescue a community from evils which are not commonly understood, is to court calamity and provoke defeat. Intelligence must grow, and moreover, it is a great mistake to suppose that men reap no benefit while intelligence is growing. Those who work towards reform enjoy their work, for every step they make, every error they overthrow, every addition they make to the structural beauty of their system, are triumphs which bring mental satisfaction and renewed vigor. We must remember that in altering mens' opinions we alter their institutions. The system which trusts to reason then, can be shown to bring the present generation some practical benefit. But what benefit can a forcible revolution bring? Does a forcible revolution not sacrifice one generation and leave it a wreck? It is a mistake to suppose that by trusting to reason alone, we place reform at an unreasonable distance. It is the nature of all improvement to be slow, and its results though long in preparation, are apt to appear suddenly and startling. It requires even now no extraordinary sagacity to perceive that the most enormous abuses are hastening to their end: and there is no enemy to this auspicious crisis more to be feared, than the well meaning but intemperate advocate of force.