Firstly, authors of the 1997 Bicentenary Research Project's essays were asked to write them in an innovative way so that they would be interesting and attractive to as many general readers as possible. Authors were also asked to keep in mind. the possibility that the research might be adapted for the stage or made a basis for poetry or song.

Thinking about these suggestions and about the need to cover a long period of time in a comparatively short number of words, I came up with the idea of 'snapshots', that is, detailed word pictures illustrating a key event. In this way, the chain of snapshots develops an immediacy not always found in the usual extended narrative. These snapshots, called in this work 'Datelines', should be read as though the words were being spoken by a George Negus-type reporter standing on location, microphone in hand. It is as though this 'everyman' is speaking history directly to you, the audience, as the events are acted out behind him, or her.

The style of language in these 'Datelines' changes as the time line advances and one could envisage the costume of the reporter changing also, from one period to the next.

The major problem to be overcome with regards to the essay's content was that most people likely to read this would already have firm ideas about what the words 'labour movement' mean. They would expect, I think, a chronologically-organised account of 'trade unions', major industrial conflicts and the establishment of the Australian Labour Party (ALP).

Whilst these cannot be totally ignored, it is my belief that this essay has to be about something quite different - namely, the social conditions in which working people found themselves and as a response to which they produced 'solutions'.

The bodies we call 'trade unions', and the ALP, were initiatives that did not drop suddenly out of the sky. They grew over a long period along with a whole lot of other responses in a rich social stew. It is that stew wherein lies 'the origins' and it is all that came out that collectively makes up 'the labour movement'. We cannot pick just the bits that agree with our point of view and pretend that they were the only responses working people made.

I have used capital letters for 'Labour History' at times in the text to distinguish a certain, 'official' record from 'labour history'. 'Labour History' is the selective account fiercely guarded by selfappointed Labour Historians who do not like their assumptions, or their methods, questioned. What I call 'labour history' is the story that emerges when we let working people speak for themselves and when we let the historical evidence lead us where it wants to go.

At this section something else that is a little different. It is a fake note prepared to look like a message provided to the authorities by a police spy or 'fizz-gigg'. The use of police informers is common enough in history and continues today, especially where industrial conflicts are likely. But this note is an invention, introduced for reasons of theatrical effect and also to suggest that such strategies were probably in play, even though no evidence of them has yet come to light.

One reads:

With Messrs J Hicks, R Ramsay, W Perry and J Mason, Mr WH Jefferson was instrumental in having the labour movement launched in the Newcastle district. It was Mr Jefferson who wrote to the late Mr Alfred Edden, requesting him to stand for Parliament. Mr Edden agreed and was the first Labour member for the Newcastle district. 1

Another claim2 credits a group of men meeting on Sunday mornings in Wallsend Park - David Watkins, John Estell, Henry Rushton, Harry Tildesley, David Broadfoot and AW Stuart, the last of whom takes the credit for the entry of Arthur Griffith into politics. Stuart says he was Griffith's organiser and after a successful campaign, '... we returned to power the first Labour Government in New South Wales'3.

Stuart recalls the district organiser at the time, 'Billy' Hughes, also referred to by GW Batey for work in establishing Greta's first Labour League. 4 Now, WM Hughes was an active organiser in the early to mid 1890s. Alfred Edden was first elected in 1891, and Arthur Griffiths in 1894.

Thus, while they differ quite significantly in details, all these recollections locate the beginnings of the labour movement in the 1890s. Most importantly, they all see 'the movement' as being principally about parliamentary campaigns.

Yet another newspaper memoir places the beginnings at or around 1883. Dated 1943, it claims that this was the sixtieth year of continuous existence of the Wickham Branch of the Australian Labour Party (ALP). The item reads in part:

(The) first Labour League to be formed in Newcastle was at Carrington. It had then been called the Bullock Island Political Labour League and mostly comprised miners from the ... colliery ... and railway workers from the workshops near Honeysuckle. 5

Though differing by a decade, the emphasis remains on parliamentary politics as the essence of 'the labour movement'. A longer series of newspaper articles, entitled 'The Labour Party - Its Early History', and centred on the 1890s, assumes that the Party was the labour movement but recalls the importance of theoretical ideas: 6

The labour movement arose during a period of industrial conflict and unrest. It was ushered in by a chaos of social theories, such as Anarchy, Communism, Socialism, Republicanism, Land Nationalism, Single Tax and Fiscalism.

Later, the author, disguised behind a pseudonym but clearly a first-hand, participant, contradicts himself and a good many others by noting the existence of 'labour movement' people who did not want to go the parliamentary road:

In the early days of the organisation there were many members (of Labour Leagues) who were opposed to the creation of a Parliamentary Party.

His own preference is clear in the title of his memoir. He appears to know a great deal about the parts played in national labour politics by Newcastle people, but those he mentions are different again:

New Lambton was the centre from which organising work was conducted, and the names of such men as Fergie Reid, Geordie Watson, Coomber and LP Vial still find a niche in the minds of the early pioneers of the labour movement7.

In an important sense, those who worked with their hands - given the limits set by their social and natural environments - were masters of their own labour and its products, and therefore of themselves.This relationship between the labourer and his labour power was transformed in the society which grew out of the Industrial Revolution. 8

In Turner's summary of his understanding of the origins of the labour movement, industrialisation caused the process of production to be broken up into its component parts. Workers were gathered into one location and the production processes were mechanised, thus separating workers from the object as a whole, from the process and also from the knowledge or the idea of what they were making.

Society, including workers' lives, was altered to fit in with and to support the new ways. Industrial cities replaced villages and countryside, workers bought rather than made what they actually needed, complex transport and communications developed and it was deemed necessary that the work-force be literate, mobile and regulated as part of a regulated production process. Workers found they had only their labour to sell, and were valued individually only as a marketable commodity.

The response of workers ….. was to form trade societies, or unions.'9

Turner's general idea is that workers needed to and began to act collectively through organisations they set up, initially within a single works, area or occupation, then over a broader area and across more occupational categories, until all were banded together as one unit with a centralised administration. 'Only in their earliest days', he claims, did societies limit themselves to the purely economic or industrial. They 'soon' moved to attempt influence on existing political parties, then to establish their own.

His own long-term response was the socialist wish-projection, that the required extension of all this activity has to be the transformation of society, having as its heart, 'common or public, rather than individual or private, ownership of the means of production'. 10

When applying his generalisations to Australia, Turner accepted that convicts could be regarded as workers but they could not. be seen as part of 'the labour movement', as their use was 'a continuing threat' to the bargaining power of free workers on the labour market. Again, free workers were heavily involved in agitation before 1851, for example against transportation, precisely because of its threat to their living conditions, yet neither their names nor their efforts apparently deserve or require recording in Labour History. 11

Turner wrote that the decades 1850 to 1890 were the years of trade union consolidation and that an employer reaction to their growing strength set the stage 'for the dramatic confrontations of the 1890s'. Since the Australian Labour Party was established during those conflicts, Labour Historians have argued, as Turner does, that the period 1890 to 1894 was 'a turning point'. This mimics the chronology and the emphasis provided for the United Kingdom by the Webbs12 and by Eric Hobsbawm's Labor's Turning Point, 1880-1900:

This volume covers the years in which the British Labour movement, as we now know it, took shape. 13

Without connecting his earlier theory to southern hemisphere realities, Ian Turner summarised the decade of the 1890s as follows. Though suffering major defeats, the

unions regrouped their forces and turned towards a new field - politics - in which they scored considerable initial success . ... By the turn of the century ... the unions had succeeded in recovering the ground that they had lost. 14

This perhaps explains why 'movement' people have been so keen to equate their activities and themselves with this period and its 'heroic' turnaround. One hundred years on, Bob Carr has claimed that 'It is the Australian Labour Party that in large measure created modern Australia'. 15

Because these claims have been widespread, readers will no doubt expect, in what follows, an emphasis on the 1890s. Research has shown, however, that there is a lot that is unsatisfactory about the prevailing wisdom. 16 Some of the evidence of this is provided here. But let me begin with a generalisation of my own.

Bob Carr's 'modern Australia', and Turner's argument about industrialisation, are part of a view which sees 'history' like a huge locomotive, moving society inevitably forward, always in one direction and unstoppable. As it gathers speed, all obstacles to its progress must be removed from the track and passengers given a clear, one-sided view: The labour movement has, in addition, seen itself as being in opposition, not to the forward movement of 'progress', but to the fruits of that advance not being equitably distributed. In its History, the labour movement has also used the idea of scattered, not-very-efficient localised groups becoming powerful only when they were locked in to supporting the centralised authority of peak bodies which became the engine in socialist theory.

Two flaws in this approach are, firstly, that the original idea of inevitable, forward progress was a wishful idea - and historians, of labour or otherwise, should never have encouraged its disguise as a fact. Secondly, though ostensibly at the centre of labour movement rhetoric and historical claims, 'the workers' have actually been invisible in Labour History. Rhetorical generalisations and theoretical requirements, largely for debating purposes, have driven Labour History, rather than honest research. As examples relevant to the Hunter. River District, historical comparative studies of settlements such as Cessnock, Bulli and Broken Hill have yet to be done. Smaller elements such as Weston, Kurri and Greta or Burwood, Borehole and Stockton have been photographed and mythologised, but have not been understood. 17

There are various ways of seeing the patterns of history. I here focus on the last 200 years by using the symbol of the station, not the train. In my vision, I can see that I am clearly in a major terminus, since the buildings are constantly renovated, are painted different colours, the platforms are extended, windows get cleaned, facilities get their names changed, pieces are added and ticket prices go up. On the track, pulsating with life, stands the centre of attention, constantly being shined and polished, repainted, but also constantly being replaced. The track out of the station is forever being swept and cleared, but no train ever actually goes anywhere. In this view, what becomes visible and crucial to understanding is the process of change and renewal, within which the cycles of life and death, of blood, sweat and tears, play themselves out.

When looking at the past, historians have a choice. In telling the story of 'the labour movement', they could do as Ian Turner and Labour Historians generally have done, which is to include just those events, practices or organisations which match in aims or in timing the pre-determined outcome as set out in the socialist formula. Or, historians could choose to include everything that has happened, without asking whether it fits the requirements of the formula or not.

A third option is to fall somewhere between these two by choosing some other limitation, some other way of deciding what to include and what to exclude. Those personal memoirs, above, have done this.

Rather than chose an option, I have tried to let the evidence lead, and tried not to have a pre-determined outcome in mind. In the present case, I would have liked time to draw on all information which could be fitted into Turner's definition that 'the labour movement' was the 'response of working people to industrialised society'. This essay can only scratch the surface, but in my view, more than just trade unions and political parties must be included, even some happenings roundly condemned by socialists or ALP voters. What appears a 'wrong response' to one person will appear correct, or even the only response to someone else. In particular, working people have had to think of more than just 'the way forward'. They have had to survive.

What Macquarie saw prompted him to appoint an Engineer of Public Works, at a salary of five shillings per day, underlining the fact that virtually all 'employment' was then with government.

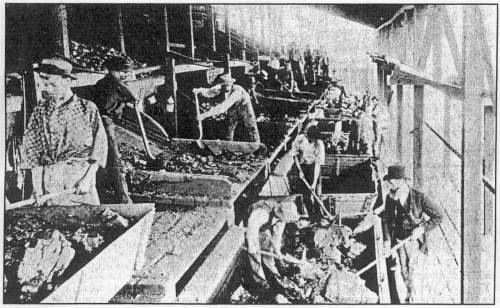

Organisational variations did exist. Convict cedar-cutters lived a month at a time up to eighty miles from Nobbys, erecting and leaving makeshift shelters as they went. Lime-burning gangs elected their own delegates daily to supervise rations and food preparation. Convicts put to hewing coal were expected to raise two and a half tons per day in drives that often lacked timber supports and were invaded constantly by water, but incentives by way of rewards for greater effort were tried as an alternative to punishment for less. Economic efficiency, and 'the public weal', were already in contention.

Commissioner Bigge, reporting on Macquarie's administration in 1821, determined that as many tons of timber were being used as tons of coal supplied. This no doubt reflected the unskilled nature of the workforce as much as its organisation. Bigge also noted that too much supervision was required and the accident rate was too high. So, it was decided that coal mining was best privatised, the Australian Agricultural (AA) Company taking over all government operations and digging its first shaft in 1827.

Already apparent by the time of Macquarie's last visit was the disadvantaged location of Newcastle in relation to Sydney. The Commandant was hard pressed to secure footwear for the lime-burners, constantly in water or walking on oyster shells. Similarly, while the burnt lime was sent to Sydney to construct imposing buildings designed to last a century or more, local construction was poor, collapsing and disappearing within a handful of years.

In 1829, the settlement still did not extend beyond that first AA Company shaft which was in Brown Street. West of the pit mouth was sandy scrub. Much further west again were the future sites of villages and towns that would develop along the alluvial reaches of the Hunter River system. There were, in 1829, only about 400 people in Newcastle, and the same number of people at Carrington, the AA Company's establishment on Port Stephens.

However, despite its size and problems with its harbour entrance, Newcastle had been acknowledged as a place with commercial potential, causing, for example, a merchant, Boucher, to print his own bank-notes and set up the Bank of Newcastle. Potential was not reality and the Bank and the Boucher store in Watt Street closed in 1830.

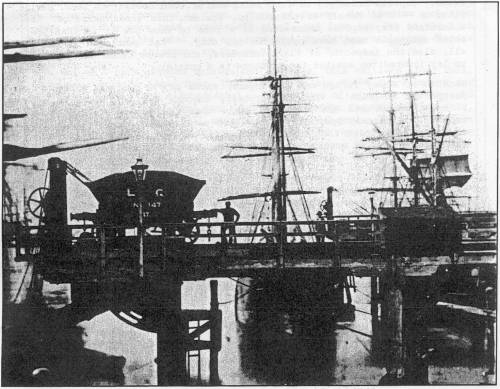

In 1850, it did appear that the Lower Hunter's promise was soon to be realised. In June that year, an exclusive dinner celebrated the first shipment of coal going directly to San Francisco. Gold was the immediate catalyst but coal was the chief driving force. Its availability and its usefulness to industrialisation meant that it became the life-blood of the Valley for the next 140 years. In 1850, the amount produced was 54,000 tons. By 1900, it was 3,492,000 tons.

These two facts do not, however, necessarily mean that industrialisation of work happened in the Valley at the same speed as the tonnage increase, or that industrialisation occurred at all. In practice, while Hunter coal was raised to drive industry elsewhere, local 'spin-off' usage was, until 1915, at a bare minimum. Its comparatively ready availability has meant that coal production and marketing have been extremely volatile and that hewers' wages and attitudes to work have always been contentious. Hewing methods have constantly changed but what was seen as important, and remains so to this day, was that the amount of 'throughput' must be constantly increased, and that the means of movement of product constantly 'upgraded'.

If steam is the necessary prior ingredient for industrialisation and thus the workers' response, then it has to be said that notable amounts of steam-driven machinery had not come to the Hunter River district before the mid 1850s. It also has to be asked whether what happened subsequently in the nineteenth century was the kind of industrialism commentators have had in mind. The importance of the Valley as a whole to the wealth and stability of nineteenth century Sydney is rarely acknowledged, but that importance was as bread-basket, quarry and site for land speculation, not as a competitor in manufactures.

The further point can be made with the help of the life of a pioneering 'industrialist', John Portus of Morpeth, whose death was announced in 186018. Arriving in the colony in 1825, he had erected machinery for the Surveyor-General, John Oxley, at Camden before moving to Segenhoe, and then Luskintyre. In 1831, he set up his own horse mill, manufacturing flour at Black Creek using the weight of cattle and horses to turn the mill wheel. In 1836, he established the Morpeth steam flour mill which produced the first bag of bakers' flour in the region and subsequently drove Sydney millers out of the Hunter market. After that time he made the Lower Hunter region a centre for the building of one-off machines and tools, mainly for the working and transportation of produce. The use of steam power is hardly what was described by Ian Turner as the set of circumstances which produced the labour movement. When, in the essay, we turn to the key 'coal' events of the 1850s we will see that steam engines had been introduced to pull coal wagons. Nevertheless rope ladders were still being used to get up and down from the pit-mouth.

Dateline ... Working Men's Institute... 9.OOpm, 19 September 1857.Hello! - I'm speaking to you from the Reading and Lecture Room of the Working Men's Institute, opened this week in the classroom under the Congregational Church in Newcastle. It is, as you can see, quite commodious, thirty feet by thirty feet at least, and is still at this hour abuzz with keen conversation, inspired by the lecture of Dr Brookes on 'Electro-biology'. The appreciative audience, in whose number I note were cloth-capped colliers alongside members of the public and commercial classes, had expected to hear Mr Whyte of the AA Company on 'Geology', but that gentleman being 'indisposed', Dr Brookes agreed to stand-in. The lecturer began by pointing out that Electro-biology was nothing more than a phase of mesmerism. Explaining the differences between mesmerism and somnambulism, he proceeded to show the means by which patients were operated upon. He then pointed out the evils which resulted from people being deprived of their natural consciousness; their exposed state while under the mesmeric influence, and the evils which might result in after life, to persons so acted upon. He contended that electro-biology should not be countenanced. The attendance was good, the lecturer applauded throughout and a vote of thanks was carried by acclamation. These are fortnightly lectures and the charge for all the privileges of the Institute is only 3 shillings per quarter. Dr Brookes, local correspondent for the Empire and President of the Temperance Alliance, is also an enthusiastic agitator for his' working men. He attends many of their gatherings and enjoins them to follow sober lives for their health and their families' benefit. He seeks to represent them and their interests in the colony's legislature. What a conversation there could have been if Mr David Buchanan, of Morpeth, had attended this night! Mr Buchanan has just launched a Working Men's Political. Association, but he would appear to have little regard for sobriety. His own appearances before the bench for robust participation with the festive glass are well known, but his erudite utterances passionately delivered to audiences large and small on the subject of liberal principles have earned him grudging respect in certain circles. Arthur Hodgson Esquire, General Superintendent of the AA Company, is in the audience, and in spirited conversation, I see, with Mr. William Wright, engineer of the firm of Messrs Randall and Wright. No doubt, coal and steam would be topics touched upon. Mr Wright recently completed the earliest trials of the first working rail engine in Newcastle. I know Mr Hodgson complimented him on speeds attained from Hexham to Honeysuckle Point on Regatta Day pulling twenty loaded wagons of earth fill for ballasting this end of the line. They no doubt shared a laugh to think they had silenced those wise people who shook their sagacious heads whenever the opening of a rail line to Maitland was spoken of. Mr Hodgson also seeks a parliamentary billet. He works closely with his employees and, I understand, is well liked for his donations to hurry on repairs to the school at Pit-Town and the building of a mechanics institute. In May this year, he reminded the workmen of the Old Rows, Happy Flat, the Borehole and Pit-Town of their employer's generosity. He stood under the Company banner toasting success an prosperity to Mr Whyte's first pit with bumpers of best English porter, and invited the men to organise their own sick club, by putting aside one shilling a week. 'Should sickness or misfortune overtake you', he said, 'you would derive relief from such a fund, and it would assist to unite you in ties of friendship and good-will'. What his employees thought of his offer to have Mr Corlette, Company official, to act as the club's treasurer, or that they could confer an honour upon him, Mr Hodgson, by electing him president, is unknown, but a club is believed to be in operation. The men are in no doubt that Whyte 's pit is a duffer and will not be surprised that that gentleman is 'indisposed'! In line with practices at 'home', the colliers expected an increase in their hewing rate when the sale price per ton rose, which it did in July, from fourteen shillings to sixteen shillings per ton. They sought a meeting and at least one paper claimed a strike had begun.. Mr Hodgson went to the trouble of writing to the Chronicle denying the statement which, if left uncontradicted, must have injured the coal trade both here and at other colonial ports. So far from having left their employment, he said, they went to work like reasonable men upon receiving an assurance from him that their demands should have his attentive consideration. He explained that the rise in price was only temporary and a result of extravagant demands throughout the colony for hay and maize. The men seem to have the belief that there was a tacit understanding with the Company that the scale of wages should rise and fall in accordance with the market price charged at the wharf. Mr Hodgson has only assumed the generalship this year and may have been unaware of previous arrangements. But, having convinced the men to continue working, he was expected to return to them after consideration of their demands. This he has now done, with an offer of three pence per ton advance and an undertaking that he would keep in mind the principle of a sliding scale. Certain ships' captains have said to me that they thought this a most inopportune time to raise the asking price of coal, and that a small reduction would have been a wiser adjustment to make, in order to consolidate the rising faith in Newcastle as a steady supplier of coal at moderate prices. Especially as the arrangements for loading coal remain in such a parlous condition. They pointed out that the Chamber of Commerce has written to the Secretary to the Minister for Lands and Public Works, stating that the port had fallen into a state of decay and neglect. They were able to point out to me the ruinous state of Queen's Wharf , the front of the quay having fallen into the river. The so-called ballast wharf - the only one available for steamers - was fast falling into a similar state. The coal channel was filling up, ships of larger burden having to incur huge lighterage fees to complete their loading in the middle of the stream. There were only two Pilots and often neither were available when needed - I thought my complainants might ignite at this point, so I opined that an encouraging reply had been received from Sydney, and that it was believed that work of significance might soon change the unhappy situation. A dredge had been mentioned, as well as the introduction of large amounts of ballasting material as parts of a great scheme of harbour improvements emanating from the brain of Harbour Engineer, Mr Moriarty. This intelligence, and the arrival of further supplies for the inner man, brought a meditative quiet. However, refuelling only warmed the coals of disputation amongst my companions, and they urged that I note the dangers inherent upon any introduction of short hours into this art of the world. 'In Sydney, the stonemasons, bricklayers, carpenters and-joiners, they're all demanding eight hour days and they've established a Labour League to get it. They had a big march last year, and they're doing it again next week - what if it catches on here, and the miners only work eight hours, or the shops are only open during daylight?' Not wanting to arouse them further, I refrained from giving them the benefit of a document I had recently come across, in a by-way near the wharf. (It is reproduced in the following section). I know not whether it is genuine, but it seems to give details of a meeting of miners from the AA Company club and the same from the Tunnels on the 8-hour question. I turned the talk to the dreadful accident that day on the AA Company's tramway. A fourteen-year old lad, Joseph Newman, apparently fell under the wheels when he jumped down to get a drink at a house along the way. His job was to hitch an extra horse onto the train of coal wagons where it has to ascend a rise. This is not the first time a boy employed in this way has been smashed up by the wagons. It may be just as well that heavier rails are being laid for Manchester-built steam engines to do the work.

|

The Sydney Morning Herald in an 1854 article `The Faults and Follies of the Wage Movement', berated 'irresponsible and insolent clubs' and their 'self-nominated chiefs and agitators' on 'Committees of Delegates' in terms familiar to scholars of twentieth century industrial relations:

The matter at issue is ... whether (the Masters) shall admit the interference and control of a third, independent and unwarrantable party - whether they and their men shall in future be at liberty to make contracts and act together as they please .. 19

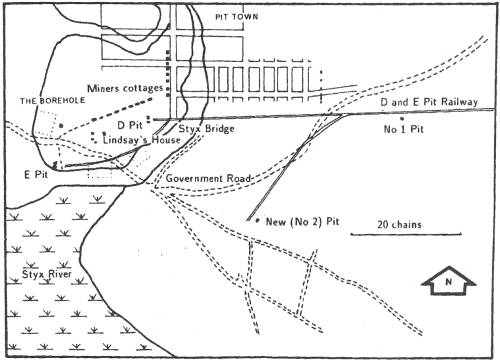

In May 1857, a speech by Superintendent Hodgson at the turning of the first sod at the new AA Company pit20, led to the setting up of a 'union-club' by colliers in an open-air meeting near the present Baptist Church in Laman Street, Newcastle. 21 Referred to by 20th century authors as 'Borehole Lodge', this is almost certainly the Hunter's first 'trade union, as has been claimed. 22

The ironies are two-fold. Firstly, it is the Company urging the miners into combination; secondly, Hodgson's speech was preceded by a great deal of Company hoopla for what was obviously seen as an exciting, new beginning. The Company's large banner led a procession from Newcastle proper along the rail line towards 'D' and 'E' pits and was used to mark the spot where Mr Whyte believed drilling would discover the Borehole seam. (See map p. 85) Whyte's credibility was destroyed when the hole, 'Borehole No 1', proved 'a duffer', as did the second, later attempt. In July, his 'indisposition' resulted in Hodgson giving his colliery manager an ultimatum - sign the pledge or take the sack.

Hodgson was already laying out the township of Pit-Town, part of present-day Hamilton, and privately revealed he believed 'nothing can give coal proprietors greater command over their men than having them located on the spot and rooted to the soil'. He also wrote:

The miners unfortunately have very little idea of assisting themselves; there is no combination amongst them save when a 'strike' is in contemplation. 23

On the day of the new pit, he told the crowd that Whyte had told him 'that you are the most industrious; well-conducted, and contented set of men he ever had to deal with'.

At the time, the word 'lodge' was used almost exclusively for Masonic and Friendly Societies and the name 'union club' was commonly used to distinguish a benefit society for colliers. It is only later, as political propaganda becomes allimportant, that these 'clubs' were seen as dangerous by employers while their advocates emphasised more of the trade protection function over the insurance functions. Logically, the two aspects cannot be separated. They are inter-related parts of the larger, mutual aid and self-help whole.

'Rules for the Mutual Benefit Society of the AA Company's Colliery Establishment at Newcastle, NSW' were published in 1858. They show that administration required a committee of twelve 'exclusive of the Treasurer, Sub-treasurer and Secretary'. Mr Corlette was 'requested to be Treasurer', his job was receiving and banking members' subscriptions and providing half-yearly accounts. Payment of the Lodge Doctor was to be done by Hodgson out of half of the funds set aside as the `Medical Fund'.

The 'Objects of the Society' show clearly how what are now called 'industrial' demands would grow from an initially generalised call for `provision ... for mutual comfort and support in the day of adversity'.

The changeable state of human nature and vicissitudes to which man is exposed in this world, the accidents to which he is liable, and the sickness and decay to which his perishable nature is constantly subjected, render it a necessary duty to make such a provision as reason and experience shall dictate for mutual comfort and support in the day of adversity. (My emphasis)

It had been AA Company recruiting and placement policy from at least 1850, that is, before Hodgson, to 'break up local loyalties and combinations'. The miners had resisted such attempts to determine who they lived and worked with, who they conversed with or sat next to in chapel, but now they were being urged into combination, because the Company suffered loss of continuity in production when its miners or their families were significantly upset. The fact that provision for 'the day of adversity' was to be interpreted differently by different peoples or that wages and security of work were inextricably part of the same context in which sickness and accident benefits were sought, cannot and has not altered that.

Whatever ideological use has been made of it since, this is a mutual benefit society. It was a straightforward response to shared living conditions. Needing protection from injury, loss of wages and sickness, families, through their male breadwinners who were agents of the whole group, helped themselves by banding together. There was no restriction on what issues could be brought to meeting, clause 5 and 6 simple referring to 'any purpose connected with the society' and 'general business'.

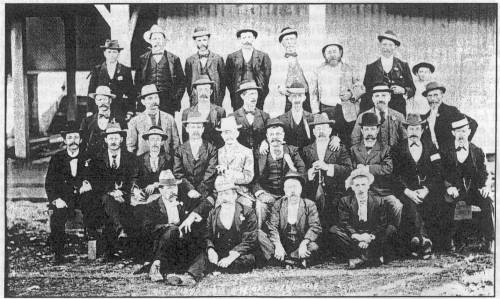

Within such a Society, and there are twenty three colliers actually named in the Rules, as Secretary, Trustees, and so on, there would have been many who could not read or write their names, and who would blush if addressed in meeting, and there would have been some similarly skilled as erudite and smooth George Curless whose speeches are recorded at length. There would have been scoundrels, drunks, visionaries, natural leaders and some just looking for a quiet, comfortable life, preferably on the surface. Nevertheless, all officials apart from Corlette and Hodgson were elected by the 'whole of the men and boys employed'. Thus was democracy in 'trade unions' instituted in the Hunter River district.

The period 1857 to 1861 was a time of great turbulence in Newcastle. Coal mining boomed, albeit from a very small handicraft base, and working people organised their first significant institutions.

Pit-top settlements are a neglected source with regard to the origins of 'the Australian labour movement'. If thought of at all, they have been treated similarly to other rapidly-expanding industrial towns, such as Manchester, but these Hunter settlements were mere clumps of existence on the furthest margins of industrialisation and all community infrastructure had to be built from scratch.

Much closer equivalents, the smaller and more 'primitive' coal villages in Northumberland or Wales, have been described by a pit man who lived in one, in the Durham area: 'each village (was) a sort of self-constructed, do-it-yourself environment. There was everything there'24. In themselves an extraordinary achievement, these village societies and their Hunter counterparts had numerous causes for celebration but were also rife with drunkenness, prostitution, and rowdy, violent behaviour. Both for Company administration and for family elders, this situation was a major problem.

Companies competed to assist the settlers into housing and the households and the economy thus created could not have functioned without the efforts of women and their close integration into pit processes. Prevailing British mores meant that it was men who conducted negotiations and had their names recorded on agreements. The small populations of the various pit villages also meant that 'Masters' were inevitably part of `their' people's games, prayers, fights and flirting and that pitpolitics included every kind of gossip and rumour.

Countering the chaos and achieving a stable and prosperous way of life took strenuous efforts on a number of fronts, including the 'union-clubs'25, temperance, co-operatives, volunteer militias and the building of township organisation and institutions - schools, churches, road and bridge systems, sanitation and water reticulation schemes, and representational democracy.

In general, village leaders used discipline and structure to build a sense of place. They were not always successful. Young men were counted ready 'to go on the coal' at eighteen, and could vote at meetings. Their emotional responses and instability were not always welcome, but then it was a time of extremes.

The existence of a union-club in itself did not necessarily change the way that management dealt with the men, nor, necessarily, the way that the miners approached negotiations. 26 However, the reports of an 1858 dispute at the Glebe tunnels indicate that a major change in relations had occurred in the preceding twelve months, and that another union-club had formed. No details are available of this at present. A third, a 'benefit society ... conducted on principles similar to those which have been adopted by the employees of the AA and the Coal and Copper Companies (that is, at the Glebe)', was first noted at Minmi in July, 1861. 27 That colliery had been operating for a number of years before the Browns took over at the end of 1859 and introduced their innovative programs. The Minmi Mutual Benefit Society with Mr William Charlton as Chairman, and Mr William Bower as Secretary, (both colliers), in August 1861, (its third half-year), numbered 200 members:

(Its) contributions for the past half-year amount to £240 2s 6d, nearly the whole of which, with the exception of a balance of £5 15s 6d remaining on hand, has been paid away for sick money, funeral expenses, and medical attendance. 28

Contracting a `lodge' doctor was by then an established practice with some 'Orders' of Friendly Societies, but not yet common with trade societies or colliers' clubs.

Around midday one Friday in March 1861, a Minmi miner was 'severely crushed':

Medical aid was immediately sent for to Maitland, but the messenger returned without being enabled to procure attendance of anyone. Subsequently, Dr Parsons was sent for and left Newcastle about 8.0 o'clock on Friday night to attend to the sufferer. 29

When lodge doctors did become the norm, 'sick visitors', that is members with the task of checking on people claiming benefits, were added to the list of elected officials. 30

In their coverage of the 'trade union/club/lodge' phenomenon in the United Kingdom, two wellregarded labour historians, Cole and Postgate, concluded:

Such trade clubs, in trades where there was not much displacement of labour or introduction of new machinery, were regarded with almost as much complacency by the masters as by the men. They were unlikely to be disturbed; but when they united together, nationally or over a smaller area, they became much more formidable and more likely to be repressed. 31

In 1860 and again in 1861, the above three 'clubs', and one at Tomago, attempted amalgamation, provoking different reactions from different coal owners. With a new colliery manager, JB Winship, reported as saying he 'simply would not have the clubs', the AA Company became quite belligerent, while Captain Williamson at Tomago continued as before. A changed employers' attitude is clear in the 1862 Director's Report of the Newcastle-Wallsend Coal Company, which began exporting in 1861:

(The major issue was) whether the unionclubs should be tolerated or put down.

The Browns, proprietors at Minmi, acted as feudal lords and, in 1860, evicted all 'their' miners from leased housing for refusing a wage reduction. Around 100 to 120 Minmi families moved, which probably means that out of the 200 Society members noted above, perhaps 120 were heads of households while eighty or so were single men living `at home'. 32

Incidentally, the 1861 Census disclosed populations comparatively swollen in the preceding four years but still quite small. At the port of Newcastle, there was a total of 3,719. At Burwood (consonant with the Glebe) there were 860, at Pit-Town (Borehole) 857, and at Wallsend, 461. The number of miners, that is `on coal', in total was 979, and in the same year company employee numbers were - Coal and Copper (Burwood) 500; AA Company, 270; Wallsend 105; Minmi 150; and Tomago 35, totalling 1,060. 33

The major disputes of 1861 and 1862 produced little joy for either side. These disputes did teach employees and employers that any contributory society was inherently vulnerable to a break in subscriptions, and that coerced payment or attendance to one's 'duty' was not as effective in the long-term as self-generated discipline.

The Rules of the 'Coal Miners Association of Newcastle, New South Wales', published in August 1861, clearly show that this amalgamation was a contributory benefit society as the 'lodges' were. The twenty-eight clauses do not separate so-called 'friendly society' functions from 'trade union' functions. They set a maximum and uniform day's wage and the weekly membership 'sick' contribution of three pence paid each Pay Saturday34 Strike pay was not yet listed among the benefits.

The Rules also show that those driving the idea forward were committed to a 'modernised' administrative and financial approach, emphasising sober and orderly behaviour, stability and representational democracy in the organisation. Specific biblical phrases do not occur but Christianity's contribution to this approach, and its insistence on workers' rights, is plain. What was moral righteousness for employees, however, was inevitably seen as attempted coercion and blackmail by employers.

Twelve months of disputes after August 1861 broke the subscription base of both this body and its constituent lodges, but since injury and medical insurance were so necessary, this is also the decade in which other kinds of benefit society extended their reach. There were local 'Yearly Societies'. There were commercial entities such as Mutual Life Provident companies. There were specific purpose schemes, for example, for homeloans35, and there were what are today called Friendly Societies.

It is not clear which `branch of the Oddfellows' Hodgson was referring to as having thirty AA Company employees as members in 1857, but it was probably the Loyal Union Lodge, Manchester Unity. 36 Societies such as the various Orders of Oddfellows, Druids and Foresters were already aware of the advantages of federating and centralising their organisation and of the need to live down their reputation for unrestrained conviviality.

Branches of new Orders emphasising sobriety and loyalty to external authority were also appearing as part of the mid-century search for stability and protection - abstinence Orders included the Rechabites and Sons of Temperance and there were the culturally sectarian Protestant Alliance and the Holy Catholic Guild. All of these `Orders' spread rapidly after 1861. 37

Lankshear and Sloggett, local Hunter historians, have emphasised the influence of organised religion on attitudes and expectations in the latter part of the nineteenth century, especially, in the Newcastle area, of Methodism38. Lankshear has provided a map of the connections between the spread of collieries and of congregations. There was a 'fit' between the percentages of the population attending the various denominations in Newcastle area and the rest of NSW39, up to approximately 1850, but from that point, the percentage of Presbyterians and Protestants, especially of Methodists and Primitive Methodists, rises to well beyond NSW percentages, while the Roman Catholic percentage declines in comparison. Between 1848 and 1861, twenty-three new congregations were created in the Newcastle region, and of these, ten were Methodist, five Wesleyan and five Primitive Methodists. Further, they were especially active: in 1861, Methodism with 13% of adherents had 45% of the congregations, of which 99% attended church regularly.40

The Primitive Methodists were fond of 'camp meetings', beginning with a 'singing and praying' procession around and between the one-roomed slab huts, lean-tos and tents that were the colliery 'townships', drawing people to a spot where the preacher would simply mount a tree stump41. These passionate worshippers held music and debating in high regard, but vilified exaggerated display, dishonourable behaviour or licentious living.

Significant temperance agitation came to the Lower Hunter settlements from Maitland in 1860. 42 A Presbyterian church was opened by Dr Lang at Pit-Town, in May 1860, Hodgson chairing the 'tea meeting' which was attended by around 500 people, mainly colliers and their families. At the end of the decade, the Seamen's Mission was an even more occupation-specific initiative to protect workers from alcoholic excess, exploitation and moral depravity. 43

Sloggett argues, from electoral and other statistics, that non-conformist religion 'cannot totally explain support for the temperance movement', but asserts that the noticeable reaction against the consumption of alcohol after 1860 and up to World War One was part of the working class response to poverty and the dangers associated with their work and living conditions. Drinking to excess was a threat to families, to the capacity of any individual or group to maintain continuity, let alone respect and dignity, and among workmates, it was a threat to life and limb:

Support for total abstinence in Newcastle and the South Maitland Coalfields was not an alien imposition upon the people. It was part of the cultural baggage brought from Britain by those who also brought trade unionism. 44

What is crucial to understand is that the momentum of 'modernism' was towards greater organisational formality, and that Methodists and Orders such as the Oddfellows initiated the first steps.

Representational politics were first experienced in this context and, like temperance, appeared up the Valley before coming to the port. On the coat-tails of the Working Men's Political Association at Morpeth, and a Liberal Political Association set up in Maitland in 185845, the Newcastle Chronicle, a paper devoted to 'liberal and reform principles', was established in August 1858. 46 The proprietors were Eurasian entrepreneurs who immediately enlisted the local expert on mesmerism and abstinence, Dr William Brookes.

Legislation extending suffrage to adult males was gazetted in 1858 and contrary to Ian Turner's assessment of 'labour movement' practice, the colliers' own representative, Thomas Lewis, was put into the NSW Parliament before their first attempt to combine 'sick-clubs' achieved success. For families sending their men off to labour in dark, stuffy and dangerous tunnels, an amalgamated association did not seem as necessary as a voice in the parliamentary process.

Lewis was not universally popular but, in any event, money was scarce. In December 1862, he resigned his seat and accepted an offer to be a superintendent of the Coal and Copper Company's mine at Glebe on the same day his former workmates went on strike. 47

In 1860, Dr Brookes was opposed to the Robertson Land Act, while Lewis supported it, and popular opinion was that free selection was the way to relieve urban poverty and unemployment reported on in 1860. After failing to carry campaign meetings held at the pits, Brookes undertook to nominate Lewis:

Though he might not be possessed of so much brilliancy, perhaps as others, still he was a religious and an intelligent man, and one possessed of strict integrity. 48

At the same election, Buchanan successfully stood for Morpeth. His advocacy of the Peoples' Charter in England had produced an experienced streetspeaker with a well-developed program: he wished to see the NSW Upper House abolished, compulsory universal and secular education, payment of members of parliament, an end to stateaid for religion and an abolition of Chinese immigration, but he favoured locally-elected magistrates and a railway for Morpeth. He was the only Protectionist in the House for two decades.

Lewis expressed himself against the Morpeth railway, being state-funded and Chinese immigration, and for the eight-hour system, payment of members, the Robertson Land Act and an elective Upper House. He was also reported as saying:

He wished to draw the attention of all, rich and poor, to one fact, and that was that he had never stood in such a position as he then did . ... He was a poor man and as yet had done nothing. (He wished his master fie his employer] to know that he) had had no hand in the late disturbances; he had never done anything to make a disturbance between man and man . ... If he was not well up in politics, there was one subject that he was well up in, and that was ventilation.

Dateline ... Newcastle Courthouse, 12.00 noon, 12 December 1860.What a year, and what an election I have just seen! This year, around seven hundred feet of new wharfing has been built, substantial success has been achieved by the steam-dredge and the excavation and transportation of coal has been transformed. We have had the Minmi, 124 feet of coal barge, built by Mr Thomas Adams at Honeysuckle for the Messrs Brown, and launched sideways into the harbour. The Dooribang steam-tug has also been bought by the Browns, and for the first time the weekly export of coal from the Minmi pit has exceeded that achieved by the AA Company. This year also, a new patent slip at Stockton has successfully taken up vessels of 300 tons, and the first trials of the steam crane constructed below Watt Street by the Government for the Wallsend Company are now anxiously awaited. Two Rochdale-style co-operatives49 have been started by working men of sober, industrious and frugal habits, one at Pit-Town and one in the western part of the port near Honeysuckle. The Bon Accord Co-operative, as the latter is known, intends to establish reading rooms, offices and a store entirely on the cash system, and to set aside monies for an educational fund and to assist the temperance struggle. A major boost to the abstinence cause was the opening in May of the commodious, brick Presbyterian church in Pit-Town, Dr Lang, Superintendent Hodgson and Mr Moffitt being much in evidence. 'The Heathenism of Popery Proved and Illustrated' was the title of a lecture by the Reverend William McIntyre in the Free Church, West Maitland in March. Dean Lynch appealed to Catholics not to allow themselves to be betrayed by any act of violence despite such offence to their creed, but he, alas, was unsuccessful. As the Reverend McIntyre's coach cue to the Free Church on the Sunday, he and his family were subjected to abuse and attempted blows, all making good their escape except Mr John McIntyre who was extensively bruised by the excited crowd. There followed a month of emotive addresses, visitations by special constables and numerous arrests. Eventually an uneasy peace was restored. The harbour remains difficult - an extraordinary weather situation on 11 July caused the death of a number of seamen and the wreck of numerous vessels. The coastal fleet setting south from here with a gentle north-easter found the wind freshening and swinging to the south so strongly they all returned to Newcastle and attempted to gain the inner harbour. At one stage, at least sixteen craft were crossing one another in the narrow channel between Nobbys and the Oyster Bank in what was by then a gale. Inevitably, there was a collision. The chaos resulted in two pilot boats putting out and the volunteer life-boat crew making its first ever outing. Despite breaking seas, Captain Lovett and his crew were able to rescue all hands of one vessel, the Phantom. In June, a Report on the Working Class in the Metropolis had sparked agitated discussion and fuelled movements for industrial organisation, partly in response to the Government's stated intention of relieving Sydney's unemployment by assisting labourers to travel to Maitland to work on cutting embankments for the northern rail line. Delegates from the Borehole, the Glebe Tunnels, Tomago, Minmi and the new 'F' Pit, met at monthly intervals after the great gathering on the 29 May this year, each man being levied three pence to cover costs of the intended Association. Meeting once at the house of Mr John Thomas at Hexham, and otherwise at the Ship Inn, delegates reported on a difficulty with an overseer at the Tunnels, as a result of which all miners had been iven fourteen days notice to quit in June. Other matters reported on include the Brown versus Alnwick litigation, during which Judge Owens brought miners, as a class, under the Masters and Servants Act; and the action of bailiffs at Minmi of taking from the pay table on a number of occasions the wages of four men who had lost cases against the Company and who had then been discharged when they objected to being left with only their workmates' charity to survive. The delegates resolved to call a public meeting on the 1 September to protest 'this merciless act' and to submit their petition, to the Governor, for approval. This was eventually achieved by a meeting on the 13 October, by which time the Minmi miners had been locked out for refusing a wage reduction of six pence per ton. After having marched into the town with music and a flag, around 200 orderly and sober miners met a large number of their colleagues from Minmi on the Maitland train, whereupon the whole marched up (Lake) Macquarie Road with no turbulence of any kind. On a temporary hustings outside St Johns Church, Mr J Lindsley chairing, Mr Harpur read the memorial50 and Mr George Curless moved that the deputation, accompanied by two miners from each colliery, consist of Dr Brookes, and Messrs Hodgson, Lang, Windeyer, Hoskins, Parkes and Pemell. In addition to the better ventilation of all mines, remedies suggested relate to the secure timbering of main roads to prevent collapse or falls from the roof, attention to old workings, the secure fencing of all pit tops and the supply of all winding pits with conductors and properly constructed cages, the use of proper signals from the bottom to the banksman and brakesman, and the adoption of precautionary measures generally. On the motion of Mr Hogg, seconded by Mr Cherry, it was decided:

That, as the masters of the Minmi colliery have resolved to make a reduction in the wages of their men, and as those men form a part of our association, and are now out in defence of their rights, it is the opinion of this meeting that they should be supported by the miners' association while they remain on strike, and in the maintenance of their rights. A further resolution was then passed, pledging the meeting to a certain regular contribution for the support of the men on strike, and a strike committee consisting of two or more men from each of the works was formed for the management and distribution of the funds. In November, on the same day that two Tomago colliers were remanded on charges of having 'murderously attacked' Mr William Young,, the manager at Tomago, colliers from the Borehole and the Tunnels hired a train to take them to Hexham so that they could 'visit' their colleagues at Minmi. It seems that a further attempt was being made to introduce men from outside this district, all previous attempts having failed due to the new miners walking out upon being appraised of the situation. On this occasion, a meeting of around 500 miners, again chaired by Mr Lindsley, passed resolutions of support to the men of Minmi and appeals to the newcomers. As the Minmi proprietors were forced to negotiate settlement, electors pinned the colour of their favourites to their hat and walked or rode to one of three polling places, here at Newcastle Court House, at Mr Smith's cottages opposite the Glebe Hotel, Burwood, or at Mr John Hannell's cottages at the Hexham Station. Defeating his opponents, land-owner Mr AW Scott and Mr Hodgson who came third, by a bare five votes out of 584, Mr Lewis was carried off on a sedan chair by his supporters towards the mines in triumph.

|

The most widely-supported demand among the miners was adequate mine ventilation and it was to obtain redress on this issue that Lewis was pushed forward. It was an issue as close as one can get to the reality of people's lives because it was about personal health and sanitation. The first speaker on the first resolution at the aggregate meeting of February 1861 was reported as follows:

He believed this question of ventilation to be of the first importance to the well-being of the miner, and its importance was manifest in a variety of forms. In that loathing of food, and the unsettled state of the stomach when food had been partaken, all arose from the effect produced on the weaker man, especially by the atmosphere he worked in. When it was considered that he had to contend with all the noxious gases which escaped from the masses of material around him, from the exhalations of his own body, and the exhaustion of the vital air consumed by the lights, it was no wonder that he suffered from inhaling an atmosphere fit only for a toad to five in. 51

The lack of toilet facilities and of fresh air were being exacerbated by the increased number of men expected to work underground for at least ten hours at a time in an increased number of pits. Lewis and others like him had been holding meetings and sending petitions or 'memorials' to the Parliament and the Governor since at least 1857, to get an inspector of mines appointed. At the May 1860 meeting, for which Lewis was the Chairman, the general aim was:

... for the purpose of initiating a complete organisation, having as its object the appointment of a government inspector of coal mines for New South Wales ... 52 (My emphasis)

In November, it was Hodgson who led the deputation to the Governor with the colliers' 'memorial' or petition, drawn up by Dr Brookes, for a mine inspection system.

The amalgamated Association was not a response, let alone an angry response, to the introduction of steam or significant industrialisation of their occupation. Neither were the colliers being separated from the production process or the object of their endeavours, nor from the idea of what they were doing. The gap between the range of their decision-making power and that determining the final destination of the coal was certainly widening, but only in backyard or 'rat hole' operations would hewers ever have had control of selling operations.

At a mass gathering in February 1861, with their Association holding together by a thread even before its strength was tested by the employers, three resolutions were presented and endorsed as a 'package'. The third caused the most dissension by seeking to set an upper limit of eleven shillings and four pence to the daily wages of 'an operative miner' averaged over a pay period. Supporters of this alternative to limiting the number of hours confronted 'the selfish and greedy' within their own ranks who were prepared to work up to eighteen hours a shift, 'two days work in each day', in order to skim the available cream, leaving the weaker, and/or steadier workers, to argue over what was left. The Borehole and the Minmi pits, which were the best and easiest seams to that point, were seen as the locations of most resistance:

The strong selfish man that could stand his fourteen or fifteen hours a day in such an atmosphere cared very little for those who were not so strong, and the weak man felt that the eight hours (principle) would not enable him to obtain the satisfaction of his desires ... 53

Three months later, in May, a majority had determined to go for time limitation by setting at ten the hours that the lifting machinery could operate. The third resolution again concerned ventilation but significantly the first argued for 'rules and discipline ... necessary for the regulating of any society'. Dissent was being silenced in the name of solidarity. A further three months later, the Rules were published showing a return by the committee to limitation by wagerestraint not by hours worked.

The old-heads, the 'unionists', sought limitation of output in order to spread the work and to make longer-term planning possible, while younger, healthier miners preferred to go for a quick nest egg to begin a family, a surface business or to gamble, fight and play as they thought fit. These are all working-class responses54, while other initiatives had implications for working people, too. Owners of self-operated businesses, such as grocers and drapers, often ex-miners and in the same benefit societies, church groups or sporting teams and needing support in seeking municipal office, also sought limits on work-time. A number of short-time, half-holiday and Saturday closing movements were initiated, involving employers and employees. Whether master tradesman, mechanic, shop-keeper or labourer, accountability, predicability and standardisation, the trappings of modernisation, were being demanded of all.

Christian fortitude and forbearance were to the fore at the pit-head and rather anxiously applauded by onlookers as the AA Company, from April to October 1862, purged its pits of all combinations and tried to force acceptance by the colliers of the Masters and Servants Act. Bent on refusing a perceived wage reduction, the Company miners were gradually replaced with 'new' men, including Cornish miners from South Australia, who only differed from the 'old' men in being in work and not out of it.

Debate raged over what money the new miners were achieving and over what the longer-term consequences might be. Thomas Alnwick, Association Secretary, pleaded for an agreement with the owners to prevent 'these pernicious strikes'. As the Minmi and Glebe men avoided temptations to join the AA Company men, James Fletcher asserted that 'the Union' was a broken reed compared to a co-operative venture then being established with the help of many of the displaced colliers. The Co-operative Colliery, Fletcher thought, would prove their hope for salvation, source of their redemption from tyranny and the only efficient method of putting down strikes.

It seems Dr William Brookes was a central player in all of these and subsequent events. When he stood, again, for Northumberland in 1862, he was soundly beaten. He had lost face with the bulk of the miners, one faction accusing him of having 'sold out' to the bosses and of having manipulated the co-operative to his advantage and that of James Fletcher, a co-trustee. But in 1869, he stood yet again and won easily over a field that included a working collier, Francis O'Brien, who urged the need for mine ventilation, for the workers to have their own voice and for Thomas Lewis to be investigated.

Dr Brookes' supporters argued that for at least fifteen years he had been agitating on behalf of the miners on a number of fronts and should receive major credit for the important legislation, the 'Act For the Better Regulation of Coal Fields and Collieries'.

Brookes had consistently advocated an Eight Hours system, but the bulk of the miners did not even want to consider it when the Association was re-established with new Rules in 1870. By this time the Co-operative Colliery had passed from the shareholders' hands, due largely to a lack of sufficient finance capital. The Rules of the new body, the 'Coal-Miners' Mutual Protective Association' of the Hunter River District, show only two objects: 'to raise funds for the protection of (members') labour, and for the support of members that may be victimised in any way (for) advocating his own or fellow workman's rights'. Strike pay, unemployed relief and a tramping allowance were the money benefits provided for, while individual lodges, as 'Accident Societies', provided a further level of cover.

The formation of this 1870 association was not a result of and did not require the coming together of the lodges as had been necessary ten years before. A shift to more centralised power had resulted in a new Rule 27 providing that 'This Association shall be sub-divided into Lodges', and other rules prescribing how lodges 'shall' be run.

An 187455 agreement between the coal owners and the Association saw the wheel of announced policy turn once more. Clauses included work limits of ten hours and a system of compulsory dispute arbitration. In practice, debate and physical struggle continued in the pit and in homes, between fathers and sons, but for a time, coal company owners and managers, concerned to end destructive competition and to force up prices, saw advantages in limiting output if strikes which were becoming longer and less tractable could be ended. Their delegates worked with John Woods, Association Secretary, on a Collieries Bill incorporating agreed-upon limits and arbitration arrangements. This legislative initiative achieved very little.

The cultural gap between miners and non-miners acted as a brake on concerted action, as did the geographic distance between the port and the coal-townships. As a lone contradiction to this, one resolution adopted at an 1862 colliers' meeting, actually set up the Hunter's first Trades Council:

That a permanent committee be formed, consisting of the various trades of this city and neighbourhood, for the purpose of taking such steps as may be deemed necessary to enlist the sympathy and support of the trades generally throughout the colonies on behalf of the miners now locked-out; such Committee to have power to add to their number. 56 (My emphasis)

The newspaper went on to record that 'The committee formed in accordance with the proposition consists of about sixteen gentlemen, embracing the various trades in the district'. (My emphasis) I have not seen any listing of the people on this body, nor any other information.

A meeting of 'non-mining mechanics and others' later in the year established a Committee with a Secretary 'to wait on the masters ... with a view to ascertain their ideas on (eight hours of work) and to report to an adjourned meeting to be held on the 26th instant'. 57 This meeting, and subsequent ones, were held in hotels or in the warehouses of sympathetic employers. They were entirely male and run by strict meeting procedure, the newspaper accounts either providing no signs of dissension or showing that the meeting organisers stopped any speaker getting out of hand. Explicitly, 'politics' were to be avoided58, by which was meant advocacy, or criticism, of any particular Party or public figure.

When Dr Brookes went to the legislature, his place as Chairman of this 1860s 'Eight Hours Committee', (it was known by different names), passed to another temperance advocate, but one who was a Secularist and Free Thinker, rail worker Daniel Wallwork. In December, Newcastle members of the Northern District of what was then called the 'Eight Hours League' declared 'to all employers of labour' their intention to only work eight hours from 3 January 1870.

Apart from the colliers' clubs, the first Hunter trade or occupational societies were in Maitland the teachers (22 March 1856), the painters (10 May 1860) and the carpenters and joiners (5 June 1860 for Carpenters and Joiners Society in Newcastle, see Newcastle Chronicle, 6 November,11 and 18 December 1873). The specific initiative which led to that 3 January 1870 declaration was a meeting convened in the Frederick Ash building, by TG Thornton and George Galley, members of an (unnamed) West Maitland Society established a few weeks before. Galley especially looked forward to seeing 'a monster eight hour procession' replace the Oddfellows march on 1 January each year. 59 The same priorities, benefits and limitations, existed when activists set up, what proved to be short-lived societies. Members' contributions were sometimes made piecemeal, at regular 'lodge' meetings in regalia and with more or less of the trappings of an Order. 60

These societies all began by signing up subscribing members and formulating Rules, as did a meeting of Shipwrights in Newcastle in 1862. 61 The detail of these groups is uncertain, as they rarely advertised their gatherings or announced affiliations with electoral candidates. 62 As the miners' own organisation waxed and waned, so did their affiliation with local bodies and, after 1871, with the Sydney Trades and Labour Council, which staged that city's first Eight Hours Procession during that year. A Newcastle Labour League, with delegates Dixon and Hopkins, was admitted to this Council's deliberations in 1873. It appears to have continued until at least 1883 and will be referred to later.

Despite the 'historic' 1874 agreement and the bountiful years some have claimed it produced by 1880, stark poverty and distress were widely apparent in the coal townships. Some colliers had certainly achieved better incomes than they might have back 'home', and some families had flourished for a time, but as John Turner, coal industry historian, has explained, high company profits attracted competitors and comparatively good wages attracted an over-supply of immigrants wanting to go 'on the coal'. 63

Within the industry there were and are so many variations possible - between miners, between pits, within pits, and between companies - that there was and is infinite room for argument. The 1880s and 1890s were decades of turmoil, misery and bitterness. However golden the 1870s might have been, the gilt had quickly disappeared as relative stability evaporated. A number of Vends were tried, but none lasted. Some coal proprietors sought the help of the miners' organisation to force wages, and thus sale prices, up, and thus put an end to relentless, cut-throat competition. Even basic detail of the lodges and the Association is not known at this stage, but collectively there was too little agreement within the miners' organisation, it had too few resources in hand and too little leverage in a complex situation wherein the only certainty was that more coal was going to be produced.

Miring families in general were averse to strikes and continually sought stability through agreements with 'the masters'. They sought to avoid strikes on two major grounds - being out of wages meant that they lost their financial margin of comfort, and, secondly, 'to go out' was a morally doubtful position since a good worker was a productive worker. Biblical injunctions insisted on ethical dealings with one's employer and particularly urged avoidance of idleness. In negotiations, workers must be direct, must be unambiguous it their statements and must seek compromise through serious, fearless discussion. Upon reaching a settlement, a handshake would set the agreement in stone. In brief, miners sought to 'behave like men and to be respected in society.

On the other hand, employers sought flexibility in order to alter their minds as opportunities presented themselves. Directness, especially from one's workers, was inevitably seen as attempted intimidation, as a desire to usurp the owner's role. What miners saw as the proprietors' 'shillyshallying', and thus as extremely provocative, was for them, marketing strategy.

There were numerous attempts to set up what we might call 'labour reform' organisations and most of them and the individuals concerned have not even achieved footnote status in 'official' Labour History. One such was the Great Northern Trades and Labour Society which held a number of meetings in Kerr's Adelphi Hotel, West Maitland, in 1884, to lobby parliament to end or to modify the current schemes of immigration because of concerns about pressures on local wages.

The year 1888 deserves particular attention. On 1st September in that year, fifty three large vessels lay idly at anchor in the harbour. Their total coal carrying capacity was 80,000 tons. The district's population of 60,000 souls was enduring 'a general strike', what Sydney Trades and Labour Council described as a 'matter of perhaps the greatest importance that had come before the Council since it had existed as a body'. The port's powder magazines were guarded around the clock, the various steamships increased intercolonial freight rates by 25%, and at Wallsend, 200 troopers and 150 police set up a military camp to protect sixty-eight 'blacklegs' loading small coal. So-called 'riotous assemblies occurred at a number of pitheads.

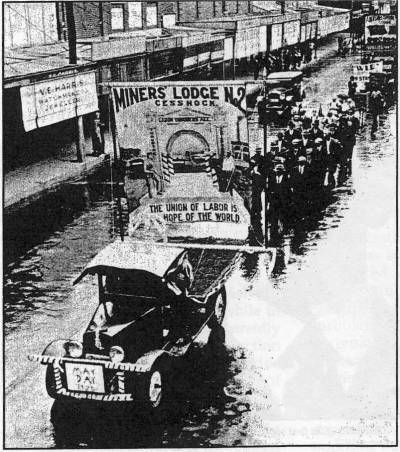

The movement for limited hours of work had, after numerous attempts, gained some momentum in non-mining areas. But the enthusiasm for 'a Demonstration to celebrate the Eight Hours Movement' in the Hunter probably came from Sydney and Melbourne's Trades and Labour Councils. The miners, for example, were holding meetings specifically on the topic, but were hopelessly divided64, when in August 1883, George Eames and WH Manuell, convenors of the Newcastle65 Labour League, called a special committee meeting and then issued circulars inviting trades to send delegates to a public meeting at the Black Diamond Hotel. Out of this came a procession, which gathered in Arnott's paddock in Cook's Hill on 17 October and marched to Honeysuckle Station. There, the celebrants joined the train for Waratah, and the Crystal Palace Gardens, to enjoy a day of sports, dancing, speeches and walks among the flower beds and animal enclosures.

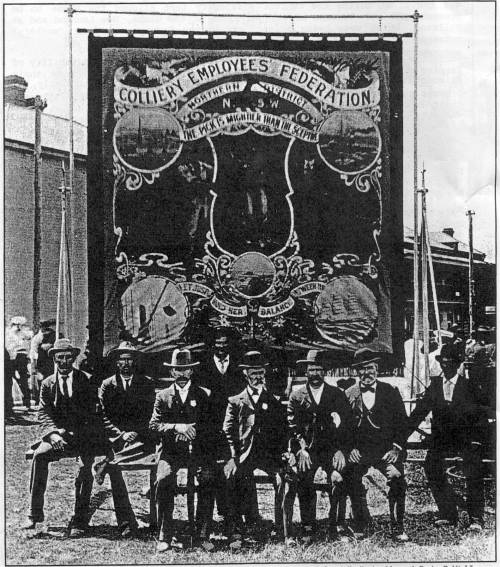

In the march were the City Fire Brigade, Lambton and Wallsend bands, the Shipwrights Provident Union (with banner), the `Building Trades', the Boilermakers `Society' (with banner), the Great Northern Railway Permanent Waymen (with banner), and Mr Ritchie's Wickham Railway Carriage Factory Employees (with banner). Mr Ritchie had taken over the chair of the organising meetings from Mr Manuell, who appears to have been relocated to Sydney by his employer, the Railways.

At the beginning of 1883, a resolution from Borehole lodge to institute the eight hours shift system from March had been endorsed unanimously by a combined delegates meeting. There followed months of arguing and overturning of previous lodge decisions if supporters of the go-as-you-please system were in the majority at any given meeting. The deadline, not even met by Borehole, was swallowed up in a decision to confer in April with proprietors on a number of matters. Although James Curley, their Secretary, was one of two joint secretaries for the 1883 procession, the miners voted in October against taking the holiday necessary for them to participate. On the one hand, they said they were still working nine hour minimum shifts, and on the other, because the previous Saturday had been a Pay-Day, thus a virtual holiday, they declined to take another so soon and disadvantage the owners. In the same meeting, the miners resolved that 'while not opposing the proposal of the Sydney Trades and Labour Council regarding courts of conciliation, we consider them inapplicable to the Miners' Association'.

A totally different format for the Demonstration was adopted the next year. Marshalled in Watt Street or nearby, the pageant would, from that time until the 1960s66, pass through the city to an enclosed arena on the western side, where entrance money could be charged for sports, speeches and entertainments.67

In March 1884, the miners re-instituted their own annual demonstration, for which approximately 4,000 people proceeded from Wallsend Station to the local athletics ground, where ten speeches were gone through before the sports could start. For some years thereafter, they marched in both the Eight Hours Day Demonstration and their own procession. The coal strike of 1888 and 1889 severely crippled the whole district and their 1889 demonstration was well down in numbers. It then lapsed until 1892, when it re-appeared, but only with difficulty. The delegates then voted away their independent stance and fell in, officially at least, with the Eight Hours Day march.

These processions and sports provided fun and a family day-out, but they were primarily fundraisers, the provision of a suitable meeting place being the stated reason for setting up the Committee. Ironically, when land for a Trades Hall was granted by Cabinet in 1892, with a £500 grant to be used within three years, there were few local funds to be raised. The year that the first Newcastle Trades Hall was opened, 1895, was the first since 1883 that no Eight Hours procession was held.

Besides having to maintain investors' margins, the coal companies were struggling to service interest on debts incurred in heavy schemes of capitalisation and were pressuring wages downwards. In addition, a new Police Magistrate in 1894 enabled local municipal rates paid by the companies to be reduced by enormous amounts, leaving a number of local councils virtually bankrupt and hardly able to pay expenses, let alone carry on necessary works.

There were other issues aggravating a difficult situation: the miners' insistence on independence, the question of how any time away from work was to be spent, how 'Labour Day' itself ought to be celebrated, and the role of women. A further issue was how independent Newcastle or the Hunter River District could be or should be, with the centralising and hierarchical tendencies of Sydney officials being always apparent.

A second Newcastle Trades and Labour Council, established in December 1885, at Tattersall's Hotel, wanted 'to conduct (its) own business without referring to Sydney'. Convened by the Eight Hours Committee, its personnel resembled the membership of that body. For the first meeting, ten miners' lodges provided delegates to sit with representatives of seamen, stonemasons and ironmoulders. But although it drew up Rules, took fees and elected sub-committees in the usual way, this Council did not last. The important relationship between itself and the miners' association was never clarified, it was not able to settle the first and only dispute it attempted to handle, between Dalgety's and coaltrimmers, and it was not able to prevent the Sydney Council being called upon to intervene. Some meetings expended themselves discussing delegates' expenses and nothing else, and it appears to have run its course inside six months.

As the first 'Labour' candidates were jockeying for position to contest the 1891 NSW election, two `Labour Electoral Leagues' contended for the hearts and minds of Newcastle electors. One, the Newcastle Labour and Political Labour League, appeared to have the better of debates, although the second, the Electoral Labour League of NSW, was the child of the Sydney Trades and Labour Council and some of its most vocal supporters, for example, Methodist preacher JL Fegan, who headed the Eight Hours Committee. Daniel Wallwork deplored the situation and urged acceptance of the Electoral Labour League, though he was an executive member of the Political Labour League.