Sydney Libertarians and the Push

On a hot January day in 2001 I found my way to the National Archives building in Canberra. My time was limited, but I had already submitted a request to see Darcy Waters ASIO file - all ten pages of it. It seems I am the seventy ninth person to access it...(Series A6119 Item 820).

The first several pages are a security assessment in 1952/53 initiated by the Public Service Inspectors (P.S.I.) office due to Darcy applying for a Commonwealth Public Service position. In a memo dated October 21 1952 we learn that Darcy:

In a memo to HQ, ASIO on June 4 1953, the regional director for NSW supplied personnel particulars collected by the P.S.I.:

Darcy Ian Waters was born Casino, NSW on 14 May 1928. He was educated at Casino High School. He was applying for a clerk position (third division) in the public service. We find that his reference is from AJ Baker, Lecturer in Philosophy at Sydney University. Baker "is not adversely recorder at this office".

The assessment by Director, B1, was that there was "insufficient evidence of any significant association with communist activities". It seems that the PSI sent several letters to Waters, which were not acknowledged. Eventually the Public Service Inspector's office assessed him as a "no hoper" on account of the non-acknowledgement of PSI letters.

The following few pages are a ASIO case officer's report, including comments by an informant, on the Libertarian society, dated 16 September 1959.. It provides some more perceptive comment on Darcy Waters and other Libertarians:

Point 9 in the report attributes to Jim Baker "that as far as revolution is concerned the Libertarian Society has its share of revolutionaries, such as WATERS, and the majority of the Bulgarian anarchists, plus a few Australian anarchists who wouldn't hesitate to drop a bomb on the Sydney Harbour Bridge or de-rail a train." It reads like Jim Baker new who he was talking to and was winding them up with the romanticised image of the anarchist as bomber. Certainly the 'source' was much impressed by Jim Baker, and almost idolized him as the exception to the obtuse ethics and standards of the rest of the Push. Or maybe the informant wished to stigmatize the libertarians by asserting a (mythical) association with revolutionary violence, rather than just revolutionary rhetoric and personal and sexual freedom. Perhaps the joke is really on the informant that he believed everything said to him without question...

I found the comments by the informant at the end of the report interesting in showing their perceptiveness of the Libertarians, but also the informants inability to grapple with the philosophical framework that underpinned the activities of the Sydney Libertarians:

At first meeting with these people one is inclined to regard them as an offshoot of the 'beatniks', but after knowing them a short while it becomes obvious that they are well above the average 'beatnik' intellectually. Their knowledge of Marxism is surprising and their ability to discuss this subject on levels not encountered in the C.P. of A. is both stimulating and educational.With the exception of Jim Baker, the Libertarians have absolutely no standard of ethics. Their behaviour and conversation in mixed company would be regarded as 'shocking' even in 'modern' society.

They have no respect for person or property and live entirely within their own periphery of standards, which can only be described as obscure.

The problem of assessing these people is difficult, as they are highly intelligent academically, on the one hand, and yet fail to recognise the ordinary basic rules of society. They describe this as 'free thinking'.

....The Libertarians should not be underestimated despite their base outlook.

I came away from the National Archives reading room smiling to myself. Darcy Waters certainly lived a bohemian life based upon using his wits. But it was also a political life, some of which was revealed in the file, but without much comprehension by the various case officers, and informers.

John Englart

from Jump Cuts - an autobiography

by Sasha Soldatow & Christos Tsiolkas,

1996, ISBN 0091833310 Vintage (Random House)

Used with the permission of Sasha Soldatow

In 1968, I was in Sydney to see the sixth performance of Hair. I knew no-one in Sydney, but that didn't stop me from going. At the last minute before leaving Melbourne, I was introduced to Wendy Bacon. She was at La Trobe University selling Thor; an underground newspaper. 'Go and see Darcy if you haven't got anywhere to stay. Our room's on the top floor,' and she gave me an address in Oxford Street, opposite the Supreme Court. I'd never heard of Oxford Street, which was then a centre for illegal gambling, and I'd known Wendy for less than an hour.I followed her instructions, got in through a back street. It was about three o'clock in the afternoon and I found this man, Darcy, lying on his bed, not fully dressed, reading and smoking, with the room in darkness and a reading light on.

'I'm a friend of Wendy's,' I said. 'She said I could stay here.'

'Yeah,' he said, momentarily looking up from his reading. 'She always says that. You can stay in the room downstairs. ' And continued reading.

I stood for a moment. Darcy looked up. 'Is there a problem?'

'Should I have a key?'

'Nah, we never close the doors. What's there to pinch?' He didn't ask my name and lit another menthol cigarette. 'The toilet's down the hall.' Then added, as if to no-one in particular, 'They make a good cappuccino in the Balkan downstairs,' and resumed reading.

My room had nothing in it except for a bare mattress on the floor and a wine glass of what appeared to be congealed blood by the bed. I stayed for two days, eating takeaway chicken, felt like one of Raymond Chandler's characters in trouble, and liked it.

Later, when I met Darcy again and was introduced, he said, 'Yeah, we've met,' and continued with his previous conversation.

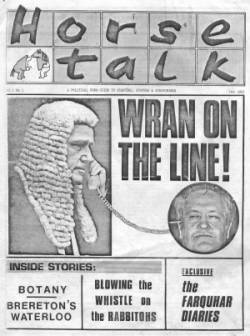

In 1983 Darcy Waters published an anti-corruption newsletter, called Horsetalk, which focussed on corruption within the N.S.W. Labor Party then in office at State Government level, the police and justice system, and links with the gambling fraternity and organised crime, including links to the U.S. Mafia. The publication was subtitled a political form guide to starters, stayers and scratchings.

In 1983 Darcy Waters published an anti-corruption newsletter, called Horsetalk, which focussed on corruption within the N.S.W. Labor Party then in office at State Government level, the police and justice system, and links with the gambling fraternity and organised crime, including links to the U.S. Mafia. The publication was subtitled a political form guide to starters, stayers and scratchings.

At the bottom of the editorial page of the first issue, May 1983, he warned potential litigants:

The publisher believes the material in Horse Talk is accurate. Much of it was given to him by lawyers, journalists and fellow punters who have been unable to have it published because of the libel laws. The libel laws are constantly being used by politicians to stifle the press and, where possible, to line their pockets.For Sydney's top lawyers, defamation is big business. The 'Horse' wishes to make it known to his readers that he has no money with which to pay his own legal costs, let alone anyone else's. Damages are obviously out of the question. Apart from that, he will be prepared to settle any other disputes about accuracy in the Supreme Court before a judge and jury.

It seems the publication was very well circulated by additional photocopying around offices of power and privilege, a circulation beyond Water's limited publishing resources. Issue 2, in July 1983, contained the following caveat:

As yet there have been no libel writs. Which may be seen to bear out my original suggestion that people who sue in the libel courts are actually interested in large wads of money, or in intimidating the big publishing houses.

A view that I would want to replace certain politicians with others is incorrect. There are indeed many I would like to see go, but, more importantly, I would like to see the actions of ALL politicians under constant scrutiny and review.

The main point of Horse Talk is to inform people of matters which the established media will not, at present, publish. Due to the Government's political censorship and control over parliament, and the libel laws, members of the public have little opportunity to develop an accurate picture of how the political and legal processes in NSW work.

Just in case anything in this publication should become the subject of a court case, I would like to remind jurors that judges are there to assist juries, not to bully them.

It is heartening to hear that many photocopies were made of Horse Talk No 1. Given our limited resources, copies will be scarce, so keep photocopying and circulating.

If you have any information for Horse Talk, I can be contacted at RPA [Royal Prince Alfred Hospital - Takver] for the next couple of weeks, and hope to be organised with a post box number for future issues.

The following editorial is published from Issue No 1, May 1983, and provides a succinct account of the reasons for political corruption and the necessity for opposing libel laws and other forms of censorship not in the public interest.

THE 'HORSE' TALKSfrom Horse Talk Vol 1 No 1 May 1983 |

ON CENSORSHIPWran did not want this Royal Commission, neither did the hierachy of the NSW Labor Party. But for the pressure of other sections of the political community, and in particular, the intervention of outside forces, Wran and his cohorts were firmly set on a restrictive and censorious course. That censorious train would still be in operation but for the fact that Chipp and the Democrats, supported by the Liberal opposition in the Federal Senate, had formed a determined plan to inquire into the judicial state of affairs in NSW. Rather than face that, Wran and Landa opted for a Royal Commission headed by a NSW judge. Even though it no longer applies, it is worthwhile examining just what that censorshlp train had in its favour for Wran. The limitations on a defamation action are well known. Its terms of reference are extremely narrow and it puts the accusers at a great disadvantage. In this case it was even more so since Attorney-General Landa was demanding that the accusor, the ABC, produce all its evidence under the guise of having it examined by 'independent' Crown Law officers. It would have been a suicidal course of action for the ABC to take but more importantly it would have aborted the very point of the Four Corners programme. When it is the Government itself that is being examined, when the independence of. the executive, administrative and judicial arms of government is being questioned, it is simply absurd to go to that government and ask it to settle the question. That is precisely why the Magistrates wouldn't report the corruption around the court system in the first place. In such circumstances it is both traditional and vital that the issue be canvassed in the media, it is for this reason that the media is called the Fifth Estate. Apart from this the Wran/Landa course of action had two strong elements in its favour. Under a ruling delivered by Kevin Ellis, speaker under the Askin administration, cases subject to a defamation action could not be debated in the House. Even when the NSW Parliament reassembled in August, Wran would have been able to gag debate on the issue. Even that vigorous Independent John Hatton would have found it hard to break through that barrier . Second, changes made to the Evidence Act by the Wran administration meant that Cabinet minutes, and all "prescribed" interdepartmental documents, could not be examined in a court unless the Government chose to release them.

ON CORRUPTIONThe ranks of Labor supporters contain many liberals who have fought hard for justice and fair treatment on a wide-ranging front of social, economic, political and sexual issues. In the present controversy many of these people are taking not a principled but a party political stance. They are saying it is merely a matter of Wran as against Greiner, an opposition leader who stands for many of the things they abhor. As a consequence the real issues are being submerged. Insofar as corruption is treated as an issue, it is said that we should put up with a small degree since it is what makes the world go round and there's no real harm in it. This is a line that must be answered even though it is true that corruption and the bribery of public officials is a long tradition that goes way past the present government, and way past the previous administration under Askin. There are many things to be said. First two questions. Can you quantify corruption? How much of it will you stand for? The truest statement ever made on the subject of corruption is that it will surely spread unless it is checked. If you do not oppose it, it will seduce you, or swamp you. The apologists for the Wran regime will find it hard to assert that there are a large number of areas in which money is not one of the deciding factors in the decisions that are made. The process gets to a point where even the ones not on the take have to lie in order to defend their associates or tell the truth and sink the whole ship. As regards the theory that there is nothing new: What is new is that modern organised crime is a large determinant or what goes on in our society. Organised crime along the American model took root under Askin and has flourished under Wran despite several Royal Commissions. The history of the C.I.U.[Criminal Investigation Unit - Takver] report (see elsewhere in this publication) is ample testimony to the active tolerance of organised crime in our society. The most important point of all relates to the function of corruption in our society. It is a point which one would think would strike home to most Labor supporters but is certainly not confined to them. It has great relevance to all who are politically and socially minded, whether they be Communists, Anarchists, Conservatives, Socialists, Libertarians or simply people who are dissatisfied with the way in which issues are resolved in societies like our own. Most Western societies do not subscribe to and legally reject the demands of minority groups for special treatment, either by virtue of their financial position or by their birthright. However, just simply taking this stance does not remove these groups from the scene. Corruption is the way in which they regain their former status. It is the way in which groups which have privilege retain it; it is the way in which the newly rich can gain privilege; it is the way in which organised crime can function. In a sentence, corruption is the way in which the old order of special access and privilege re-asserts itself. For those who do not have access and who are not the recipients of privilege, corruption has a very distinct meaning. It means that they cannot stand up and assert/ defend themselves in the knowledge that they will get a fair hearing. Logic and persuasion do not have currency if the people in power are only listening to the jingle of money in your pocket. Those who oppose the plans of the authorities in a corrupt society will live in frustration and isolation. Those who oppose the plans of organised business and crime will live in fear. When Govemnent and crime work together, frustration and fear combine and the result is explosive.

|

Sydney Morning Herald

1st May 1997

Before he died on Wednesday just short of his 69th birthday, Darcy Waters left explicit orders for his funeral. He was not suffering from a terminal illness nor did he suicide; he simply ended his love affair with life and slipped out quietly while nobody was watching.An imposing, handsome man - his physical presence was magnetic - with an inquiring, original mind, he was a celebrity in the Sydney Push, the gaggle of intellectuals and bohemians which evolved from Sydney University's Libertarian Society.

Waters arrived at the university in 1946 from Casino to study veterinary science. But his love of discourse and ideas drew him to philosophy lectures where he was mightily influenced by John Anderson. He became a full-time philosopher outside the acaddemy - and a part-time wharfie.

The Libertarians split from the Freethought Society in the early '50s over the notion of freedom. The Freethinkers reckoned that free thought was enough to make one free; one's physical circumstances were not paramount.

Waters was prominent among a group of dissenters who argued that "freedom" was not just theory but implied having actually to live the idea.

In the button-down 1950s, this was a revelation in the city pubs where Libertarians drank and argued. As Victorian taboos and rituals were contemptuously discarded, a city subculture arose: this was the Push, named after a 19th-century gang of outlaws.

Waters had an abiding sense of fun, mixed with purpose and wisdom and a powerful sense of justice. The latter saw him involved in Indonesia's struggle to throw off Dutch rule, a battle he would later, in part, regret, given East Timor.

He was also involved in the fight of the Gurindji Aboriginal stockmen for industrial rights at Wave Hill station and in battles against censorship via Tharunka, the University of NSW student newspaper, in 1970-71.

Waters fought countless skirmishes with authority and delved into corruption in politics and big business in several scurrilous newsletters; he named people in high places long before inquiries and judicial commissions were able to do so.

His other passion was horse racing. His rangy six-foot frame, long blonde mane and decidedly yellowed, almost equine set of teeth, earned him the sobriquet of "The Noble Horse", or simply, Horse. Through four decades, he was a fixture at Sydney tracks in his curious uniform of crumpled blue country gentleman's shirt and jeans, a racing newspaper in his back pocket.

An audacious punter, he amassed small fortunes in a race day, having started with a small bank borrowed from some hapless neophyte dubbed his "captain".

The fortunes didn't last; the day's gambling continued well into the evening - at the trots or the greyhounds - until the filthy lucre was gone from his hands. If, by some chance, the streak continued, he would seek out the most obscure of country midweek meetings until it was all spent. In the meantime, he would be the most generous of people, freely lending and giving money away; this was treating money with the contempt it, and the system it spawned, deserved.

One Waters streak started with ?1. He moved among the trackside bookies in a frenzy of bets, and in between races, wagered on interstate and country meetings, often putting the winnings all up on the next horse.

On the last race he wagered some thousands of pounds, his entire winnings, on the nose. The horse lost by a lip. In the pub later he was asked how he'd gone: "Lost a quid," he said.

It was a great life and much admired - intellectually unengaged menial work followed by countless hours of philosophising in pubs and coffee shops and at parties.

Waters was an icon of freedom and rebellion for Sydney's weekend warriors, people who couldn't or wouldn't embrace a life of permanent protest.

Embodying such romantic expectations, Waters was corralled into living up to his legend while other people got on with ordinary suburban lives. He did his best.

If anyone deserved to be called a living National Treasure, to be paid a stipend by an enlightened government for being himself, Waters was such a person. It would only have been a short-term loan; he'd have returned it soon enough to the public coffers via the TAB.

Waters, who never married, is survived by a brother, Edgar.