| This is Part 2 of a pamphlet produced by Bob James for the 6th Biennial Conference of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, which was held 1-4 October 1999 in Wollongong. Part 1 is Secret Societies and the Labour Movement. Visit the Display Catalogue. |

Labour History, a political construction, is misleading history, if it is history at all. The Webbs, on whose ideology Labour History has been built, were intent on claiming to be 'modern' above all else. LH has wrapped itself in their mantle, and encouraged 'trade unions' and 'the movement' to claim to have forged a rationalist and progressive presence from a superstitious, irrelevant heritage.

The Webbs argued that lodge 'ceremonies' were used by the British 'trade-unionists' as an artifice of stage-management to impress unsophisticated newcomers. To them, the Tolpuddle labourers were merely 'playing with oaths.'[1] Under this Webb treatment the organisational function of the rite simply disappears, it is undeserving of any further exploration. The oaths cannot be part of a living culture reflective of the needs, anxieties, expectations or desires of the people using them. Thus live people disappear and only selected events and groups can be part of 'the real trade union movement.' Only committment to and membership of a certain organisational 'type' qualified someone as 'class conscious'.

The Webbs appeared to believe that the whole lodge ritual package was abandoned if not immediately then not long after 1834, the year of the Tolpuddle trial.[ 2] If oaths, regalia, initiations, etc, did actually cease at that time they should not have reached the 'labour movement' in the USA or New South Wales decades after that date, which they did.

Very interestingly, the Webbs assert that Robert Owen's GNCTU:

closely resembles in its Trade Union features, the well known "Knights of Labor"...for some years one of the most powerful labour organisations in the world' and whose place was taken by the American Federation of Labour, with exclusively Trade Union objects.'[3]It is not clear what 'Trade Union features' or 'objects' might mean here but the Knights began life in the USA in 1869 as 'The Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor'. As a 'purely and deeply secret organisation' it drew heavily on Freemasonry for its ideas and procedures,[ 4] according to the author to whom the Webbs refer, Carroll Wright, who was at the time US Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor. Wright went on to say that a major change took place in 1881 when the Order's General Assembly agreed that for the first time the Order's name and objects would be made public and its initiating oaths abolished. In 1883 the titles of officers of the K o L central executive were altered from 'Grand' to 'General', viz, from 'Grand Master Workman', 'Grand Secretary,' 'Grand Treasurer', 'Grand Venerable Sage', 'Grand Worthy Foreman', and 'Grand Unknown Knight', etc to 'General Master Workman', etc.[ 5] Wright does not emphasise the fact that significant amounts of the Knight's ritual actually continued, including the use of a square altar and a red triangular altar.

The key 'Grand Master Workman' of the K of L, Terence Powderly, described lodge practices in his autobiography including the open Bible always present during meetings of the Assembly. This is standard lodge practice, not just Freemasonry practice. Powderly had first been a member of the 'Industrial Brotherhood' which had had its own ritual. It coalesced with and passed on its Preamble and Constitution to the emerging K o L. Indeed, in the US most, if not all trade-based societies were of this form. There was the 'Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers', the 'Order of Machinists', whose emblem was said to resemble that of Freemasonry, and the 'very secretive' 'Knights of St Crispin', the shoemakers' 'combination' which at 1869 had 50,000 members and was easily the largest 'trade union' in the US.[ 6]

I don't accept that Freemasonry was the source of the Knight's lodge practices, but the evidence for that must not detain us here. Suffice to note that the co-founders all belonged to a number of fraternal organisations besides the freemasons, one, for example, being in the Pythians, the Odd Fellows, the Improved Order of Red Men, the Royal Arcanum and the Order of the Golden Cross. Powderly was in the Workingmens Benevolent Association, the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Irish Land League all of which drew on the original guild model.[7]

Although 'fraternalism' has also been neglected in the US, compared to this country there have been a lot more attempts to take the phenomenon seriously. And just as the few Australian authors who have bothered to look at primary material have been surprised and impressed with benefit societies recent US scholars have asserted their cultural and political significance. Take Robert Weir's 1996 Beyond Labor's Veil. Almost in passing he notes that 'fraternal orders' were 'deeply rooted' in American culture, that by 1901 there were more than 600 such societies in existence and that cities like Albany, Newark, Philadelphia and others have recently been shown to have been 'crisscrossed by fraternal networks as was the entire State of Missouri.'[8]

Weir agrees that before 1882 the Knights' fraternalism was marked by secret ritualistic behaviour, and orally-circulated 'secret knowledge', while after 1882 their culture was more diffuse, open, public and literary. But he argues that the growth and political significance of the Knights cannot be understood if the ritualism is ignored and that the dropping of the ritual was a major reason for the internal collapse of what was in 1886 a million-strong, national labour organisation. He notes that in the 1890's surviving Knights returned to the oath-bound ritual and secrecy of the first phase and that 'long after labour fraternalism (had) faded as actual practice, it continued to shape' the labour movements' debates, policies and values.

The Knights evolved out of the reconstituted Garment Cutters' Association as the logical, perhaps the only next stage from the disarray of 1850's trade unionism. Weir asserts that

the founders dreamed of moving beyond the limits of 'bread and butter' unionism by creating an oppositional culture based on the brotherhood of all toilers.[9]The Knight's key public attribute was, in fact, its inclusiveness. Sixty thousand (white?) women workers enrolled in the 1880's, including Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton, while by 1887 there were 90,000 black workers enrolled.

Not all of these members were impressed with being in the Knights, indeed the enormous increases in membership after the successful action against Jay Gould in 1885 exposed the executive to increased questioning for which they were largely unprepared. Weir believes the female members were indifferent to even the reduced ritual, but that the lodge practices were exactly what brought in the African Americans, many of whom stayed after the Knights had gone into decline. He quotes one scholar who has written:

Well-versed in secrecy and ritual (African Americans) were attuned to symbolism and to the 'inner workings' of the Order. They expanded their experience with self-organisation, self-education, and self-government and integrated these new experiences into their own social and intellectual frame of reference. [10]A central Knights' value was that of 'brotherhood'. While its many positive traits - family duty, personal integrity and responsibility, honesty and activism - can be appreciated this principle was invoked more in its masculine aspects of knightly honour and manly courage than in its universal aspect. Weir notes that while the Knights were attracted to the mediaeval codes of chivalry they were not deeply anti-modernist as some 19th century fraternal orders were. Rather they had a suspicion of industrial capitalism and sought to protect and rebuild the communities and the community spirit they saw being eroded. The Knight's founder, Stephens, saw the job of the fraternity to be

of knitting up into a compact and homogeneous amalgamation all the workers in one universal brotherhood, guided by the same rules, working by the same methods, practising the same forms for accomplishing the same ends...it calls for an end to wage-slavery and the elimination of the great anti-Christ of civilisation manifest in the idolatry of wealth and the consequent degradation and social ostracism of all else. [11]In these terms the subsequent embrace by the labour movement of centralised and bureaucratic organisation can be seen as a logical progression out of what to some appears to be a throw-back to archaic practices.

The collapse of the Knights was also due in a major way to the onslaughts of capitalists after 1885 and financial woes induced by its sudden inrush of members. Further, throughout the eighties it was an organisation attempting to accomodate 'assorted Marxists, Lasalleans, anarchists, syndicalists and free thinkers' as well as numerous varieties of feminists, temperance advocates, and ritualists.

As I've said, Terence Powderly, the Knights leader during the Order's rise and fall, was the key advocate of the significant shift to making the Order's affairs public. He was not anti-ritual, indeed he died a 33 Degree Freemason. Rather he understood that ritual was central to what the Knights saw as its role of educating its members about political economy and their position in society. He also knew that secret signs and passwords were necessary and had to continue no matter how 'public' the Order was. But he was a devout Catholic and was attempting to defuse the attacks coming from Catholic clergy which were impeding recruiting. Catholicism, of course, resembles the most patriotic, Tory authorities in its dislike of other people's 'secret societies'. It does so only because it cannot control those whose beliefs are hidden from it, and which are therefore threatening.

In short, Weir argues, and I agree, that benefit society ritual elicited emotional and psychic responses which the more materialist and secular labour organisations could not, and did not. He notes that Powderly and Samuel Gompers were both living proofs of the fact that 'once ingrained on the individual psyche, fraternalism put down deep roots.' In 1917 when asked to join the Knights of Columbus, Powderly refused and stormed out of the Catholic Church for good, saying: 'If it was wrong for the Order of the Knights of Labor to be a secret society in 1879, it cannot be right for the Knights of Columbus to be a secret society in 1917.' Samuel Gompers was initiated a Knight in 1873, and though his long career of labour activism took him well away from the Knights his 'devotion to secrecy was a point of pride. "I am unwilling to give the nature of the obligation..." That is he refused to reveal the nature of his oath. "..for since I assumed (it) I have never violated it." '[12]

WW Lyght brought the Knights of Labor secretly to Australia by first establishing an Assembly of the Knights at Wagga in approx 1890, and one at Sydney in 1891. In my MA thesis on the role of anarchists and anarchism in the heady days of the 1890's in Sydney and Melbourne I was able to make few connections between home-grown activists and WW Lyght and so the Knights of Labor appear there only as incidental colour. Today I feel that the almost absolute invisibility of this 'WW Lyght' person and the wider context I've been able to put together suggests a closer look might be in order. Certainly the name of Larrie Petrie will be known to some of you as an influential labour radical of the time. He was among the first to join the Knights, doing so at Wagga before coming to Sydney, before ultimately heading off to Paraguay with William Lane's refugees.

How long the Wagga and/or the Sydney Assembly, or any network of Assemblies in Australia lasted is doubtful but the membership of the Freedom Assembly, Sydney, from 1891-93, included many well-known labour-movement figures - William Lane, Ernie Lane, Arthur Rae, George Black, Frank Cotton, JC Fitzpatrick, WG Spence, WH McNamara, Henry Lawson and Donald Cameron. That it operated as a secret society is clear, but how much of the US-derived ritual set out in documents was used is not. Codes and Passwords were certainly used. Titles apparently used in meetings included Master Workman, Worthy Foreman, Past Master Workman and District Master Workman. These titles are standard lodge practice. The 'Secret Work and Instructions' contains directions for passing through Outer and Inner Veils, for hand-signs and excluding strangers, and for ritual use of the globe, lance, triangles, circles and other shapes. These are all explained in Weir's book. The 'Inner' and 'Outer Veils', for example, are terms for the ante-room and the main lodge room used to maintain secrecy. The lance and the globe, besides having various symbolic significances, were objects placed outside the one room or the other indicating the 'lodge' was in session.

The Knight's Great Seal (illustrated) was explained only to long-time devotees. Weir's summary is: The inner-most lines of the equilateral triangle signified humanity, man's relationship to the Creator, and the three elements essential to man's existence and happiness - land, labour and love. They were also emblematic of 'production, consumption and exchange.' The hemisphere represented the KOL's North American birthplace, and the inscription denoted that that the first Grand Assembly of January 1878 was the ninth year the Adelphon Kruptos (ie, Secret Brotherhood the name given to the ritual booklet) was in effect. Prytaneum was a Latin word referring to a dining hall used by the Knights as the place all looked towards. The inner unbroken circle represented the 'unbroken circle of universal brotherhood' while the segments of the Pentagon refer to its five principles: justice, wisdom, truth industry and economy. The next circle, emitting rays of light, referred to the path of learning of all Knights which took them from 'locals' to the Grand Assemblies. Then came the motto 'That is the most Perfect Government in Which an Injury to One is the Concern of All.' Lastly the five points of the star representing the five races of the earth and the five divisions in which the earth is divided. [13]

The Knight's Great Seal (illustrated) was explained only to long-time devotees. Weir's summary is: The inner-most lines of the equilateral triangle signified humanity, man's relationship to the Creator, and the three elements essential to man's existence and happiness - land, labour and love. They were also emblematic of 'production, consumption and exchange.' The hemisphere represented the KOL's North American birthplace, and the inscription denoted that that the first Grand Assembly of January 1878 was the ninth year the Adelphon Kruptos (ie, Secret Brotherhood the name given to the ritual booklet) was in effect. Prytaneum was a Latin word referring to a dining hall used by the Knights as the place all looked towards. The inner unbroken circle represented the 'unbroken circle of universal brotherhood' while the segments of the Pentagon refer to its five principles: justice, wisdom, truth industry and economy. The next circle, emitting rays of light, referred to the path of learning of all Knights which took them from 'locals' to the Grand Assemblies. Then came the motto 'That is the most Perfect Government in Which an Injury to One is the Concern of All.' Lastly the five points of the star representing the five races of the earth and the five divisions in which the earth is divided. [13]

The Instructions issued in Sydney insist:

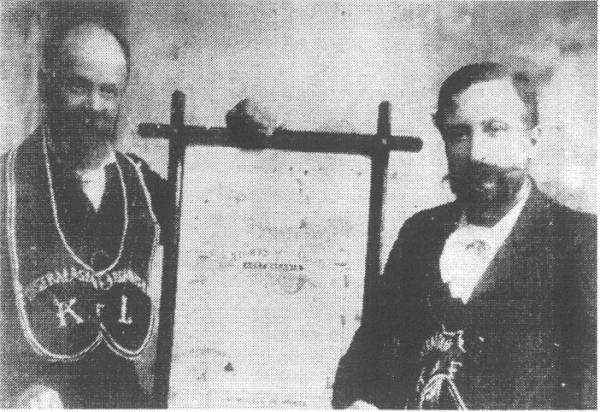

If there is any sign or portion of a sign, words or symbols, in use in your local different from what you find laid down here, discard the same at once...It is not official or authorized...Give nothing that you do not find here, and there will be no trouble from lack of uniformity throughout the Order. [14]The published Preamble for a Melbourne-based Australasian Knights of Labor, (1893?) shows the names of leading Knights, who included Dr W. Maloney, MP, alongside initials which can be read as 'Past Master Workman', 'Grand (or General) Master Workman', 'Grand Recording' and 'Grand Financial Secretaries'. A photograph of Dr Maloney and JR Davies for the Knights of Labor shows both wearing standard lodge regalia. (See illustration below) Weir doesn't provide photos of regalia used in the US apart from ribbons and badges, and does not refer to any collars or aprons. It is possible therefore that this regalia was devised and made in Melbourne.

The Knights of Labor were not a radical aberration, they were simply another manifestation of a long-standing and deeply-rooted cultural phenomenon, the breadth and depth of which is still coming to light. This is not to resurrect the arguments about 'craft-based' occupations vs non-craft-based occupations. The significance of this material is much broader than that.

If you read this material including Powderly's writings you will see that it serves only ideology to separate something called the 'labour movement' from something else called 'the lodge movement.' Weir notes that secret fraternalist ritual did not disappear with the Knights of Labor and mentions the 'Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners' following a similar mode of lodge practice when part of the 20th century's AFL. He also records the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers following 'a strict ritual' in the 1930's and auto workers in the same decade determining that their winning formula for organising key automotive shops involved first making converts among fraternal orders like the Freemasons, and 'the rest will follow.'[15]

It is not surprising to me that when the Newcastle branch of the Operative Stonemasons' Society was formed in 1885, 35 initiates were 'made'[16] or that an apron produced for the Victorian Operative Masons' Society in 1906 is identical with what for simplicity sake I'll call the 'masonic' type. [17] Tylers, or Door Guardians, are referred to in the Rules of Sydney Coal Lumpers, not established until 1882, the 1888 Rules of the United General Laborers' Association of Newcastle, and of the United Laborers' Protective Society of NSW, Newcastle Branch, 1892. This last body, of labourers mark you, lists in its assets for that Year: Banner boxes, Books, Regalia and other lodge Property to the value of £110 (out of a total £146/12/-). In addition to a Tyler the Rules of the Australasian Association of Operative Plasterers, NSW ('a grand universal bond of brotherhood' est. 1886) show for initiation of new members a catechism-form of questions and answers, strongly reminiscent of Masonic initiations. [18] Photographs of the Broken Hill Executive of the FEDFA for 1913 show all wearing the same type of embossed collar or sash as for Masonic or Friendly Society ceremonials. [19] At the laying of the foundation stone by Ben Tillett of the Broken Hill Trades Hall in 1898 'masonic' collars and sashes were worn by officials of the Committee.

Up to the 1960's in Australia the AEU and the United Society of Boilermakers and Iron Shipbuilders were swearing in all apprentices and new members with an oath.

Whatever the peaks and troughs, the evidence certainly argues that to generalise about 'Freemasonry' and 'elitism' is to miss the point and that in the decades either side of the turn of the 19th/20th century working people re-affirmed their need for the bundle of beliefs and practices here labelled 'lodge' or 'benefit society' in a number of different sites.

For example - Around 1900 enormous heat was being generated within Protestant churches over 'ecclesiastical ornaments and haberdashery'[20] and one of the more forthright protagonists, the Church of England Association reported that its church was:

honeycombed with secret societies, guilds and brotherhoods, some under episcopal patronage, yet all secretly instilling the false doctrine of soul-destroying error that underlies Romish ritualism...Ritualists were unanglican, unenglish, anti-Reformationist and Anti-Christ. [21]Given that the 'ritualism' being objected to was a symbol for the power and trappings of High Church hierarchy, the relationship of 'Masonic' iconography and 'Romish ritualism' to Labour Days must have been an issue to trade unionists whether Catholic or not. It would also seem that 'the austerity of Methodist Christianity', its 'disdain of the lighter side of life, its cultural philistinism' might have influenced the nature of labour ritual. [22] It was, however, the Catholic Church which both retained its ornate services and was increasingly significant within the Labor Party. [23] This in itself suggests either no strong interest in ALP circles in reducing ritual as trappings of a non-democratic enemy or that ritual was central to all of the organisations in the competition for members.

It's little known that Methodists and Primitive Methodists, the supposed enemies of sacerdotalism, were often Freemasons, or that the Methodist Church of Australia in 1914 began the 'Methodist Order of Knights' which had Degrees, secret handshakes, knocks and signs, a peculiar method of voting (standing, stamping foot once) and 'Courts'. Ritual was developed quite explicitly to stir and 'grab' the emotions of boys, eight to eighteen, and later adult males, as Knight Commanders. A female version, the Methodist Girls Comradeship also developed with the ranks of Senior Comrade, Elder Comrade, Comrade of Records and Comrade of the Purse, (who all wore Gold Collars) and the Guardians of Good Fellowship, of Ceremonies and of Awards (white collars). The June 1919 Ritual shows the Guardian or Order, assisted by the Guardian of the Entrance preparing the room 'as per diagram' which includes the arrangement of the officers' chairs. Various Orders were to identify themselves, as for example, the Order of Minstrelsy, 'Black Harp on Green Ribbon', or Order of the Lambs, 'Order of the Blue Ribbon', etc. Appropriately, the 1923 Amended Constitution of the Methodist Order of Knights was set out exactly as the published Rules of Trade Unions and Friendly Societies were. [24]

Catholic sodalities drew on the same sources for inspiration. The American Knights of Columbus became the Knights of the Southern Cross in Australia where they proliferated after 1918. Hogan has commented: 'Like the Masons the Knights maintained a discipline of secrecy, ritual and membership by invitation.'[25] A former member of both the Masons and the Congregationalist Church's youth section called 'The Companionship' saw 'the set up' in both as the same. [26]

Brief newspaper reports show that in the 1880's Court True Freedom, a Newcastle 'lodge' for the Independent Order of Free Thinkers, initiated new members and had ceremonies and markers for ranks and degrees. [27] This ties in with the fact that well-known English Free thinker Charles Bradlaugh remained a Freemason all his life, having been initiated into the same lodge of which Karl Marx was a member.

What the author called the secret history of the (First Communist) International asserts:

The IWMA [Industrial Working Men's Association] in Geneva sought and found a temple worthy of their cult...a Masonic Temple...which they [Marx, etc] rented. They put the name of 'Temple' on their cards and bills. [28]Bradlaugh acknowledges having been initiated into the Loge des Philadelphes which is believed to have been Marx's lodge, his 'brothers' including Blanc, Garibaldi and Mazzini. Founded in London in 1850, its initial members were emigres from recognised foriegn Orders, which perceived Freemasonry as:

an institution essentially philanthrophical, philosophical and progressive. It has for its objects the amelioration of mankind without any distinction of class, colour or opinion, either philosophical,political or religious; for its unchangeable motto: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. [29]But where Annie Besant sought to reform Freemasonry as a whole and helped to establish Co-Masonry, her one-time lover and fellow free-thinker Bradlaugh had chosen from two 'Masonic currents' he saw moving in very opposite directions. He advocated a 'Freemasonry of no religion' but thought that the European strand was made up of 'revolutionary, anti-clerical, secret societies.'

In 1897 anarchists JA Andrews, Joseph Schellenberg and John Dwyer founded on their own initiative an Isis Lodge in Sydney and attempted its affiliation with the Theosophical Society in London just when Annie Besant, labour activist, free-thinker and associate of Bradlaugh, was being installed as 'First Sovereign Lieutenant Grand Commander of the Order of Universal Co-Masonry and Deputy of its Supreme Council for the British Dominions.' It is believed she gained admittance to the three degrees of Blue Masonry, (ie, the 3 basic degrees of Freemasonry) in Lodge "Le Droit Humain", No 1, Paris. [30] Roe has commented in her study of the broad appeal of theosophy in Australia that Co-Masonry was attractive to female theosophists precisely because with the 'ancient' masonic ritual restored and women freely admitted equally with men, it was a direct response to Madame Blavatsky's urgings for a remodelled Freemasonry. Roe went on:

The introduction, or revival, of occult ritual and symbol within a masonic order was another attempt to catch the older flavour and culture of 'brotherhood'... (The) word 'lodge' was a versatile (one), suggesting cell, self-help institute, secret society all in one. [31]Theosophists were keen on social reform but Roe argues the non-democratic nature of the Australian Society is proven by its Rules which on the issue of the autonomy of Branches (renamed lodges in 1890's) say: 'Each Branch and Section shall have the power to make its own Rules provided they do not conflict with the general rules of the Society.' These latter made it clear that all authority derived from the President who had the power to cancel individual diplomas, branch charters or section rules. [32] The occult hierarchy of Theosophy internationally was headed by 'the Elder Brethren' or 'Great White Brotherhood' itself topped by a trinity representing the Head, the Heart and the Arm. [33] Roe believes that Theosophy 'offered not merely reform but reconstruction, and special promise for women.' Nevertheless female members continued to do the cleaning and decorating of lodges and when hostility broke out between founder Madame Blavatsky and Besant the former leader denounced the practice of Freemasonry:

Professedly the most absolute of democracies, it is practically the appanage of aristocracy, wealth and personal ambition. [34]Roe concluded:

(The) elitism of Edwardian social theory found one expression in Mrs Besant, who, like Lenin, was ready and willing to take command under the right conditions. [35]Furious debates over Freemasonry occurred at the (European) Socialist Congresses of 1906 and 1912, [36] and ideologues determined on a stand at the Fourth International, passing the following resolution:

It is absolutely necessary that the leading elements of the Party should close all channels which lead to the middle classes and should therefore bring about a definite breach with Freemasonry. The chasm which divides the proletariat from the middle classes must be clearly brought to the consciousness of the Communist Party. A small fraction of the leading elements of the Party wished to bridge this chasm and to avail themselves of the Masonic Lodges. Freemasonry is a most dishonest and infamous swindle of the proletariat by the radically inclined section of the middle classes. We regard it our duty to oppose it to the uppermost. [37]How successful they were remains to be seen.

Membership of Friendly Societies where ritual fraternalism was also strong was at its peak in the 1890's-1900's. This fact has added significance in this 'labour movement' context.

Chapter 4 of the 1990 'Report of the Senate Select Committee on Health Legislation and Health Insurance' begins with:

Australia has a long tradition of private hospital and medical insurance, which had its origins in nineteenth century friendly societies, church and charitable organisations.But if one goes to histories of medical and hospital services in this and other countries one invariably finds stories of and by the practitioners but nothing on the societies. Some accounts are even more remiss. The 1983 Australia's Quest for Colonial Health has David Evans' The Plight of the Poor in the Working-Man's Paradise' which quotes Serle's 1971 Rush to Be Rich as saying that at the end of last century

Friendly societies and trade-union insurance schemes flourished, but few skilled or semi-skilled workers took up the cover offered.Serle, it turns out was quoting the PhD thesis of Eric Fry, influential LH'n keen to deny legitimacy to any working peoples' organisations other than 'trade unions' or their parliamentary representatives. There is far more than ownership of 'medical insurance' at stake here, but in this instance 3 authors are recycling inaccurate history without any of them bothering to do any primary research.

Green & Cromwell who have attempted to produce useful statistics have noted that at the turn of the century it was believed that 80 to 90 % of all Australia's manual workers were members of friendly societies. Figures from mining towns like Broken Hill, Lithgow, Hillvale, and Newcastle support this. Green and Cromwell concluded:

By the 1860's the societies were a major presence in every major Australian town. They were known for their organisation of medical services, for organising the supply of medecines, for their sick pay, and for the help they gave to those who fell on hard times...The collectivist ethos of the Australian people has been written about but the popular conception is only a pale shadow of the truth. In the UK where a little more attention has been paid to them, one 19th century academic concluded that 'the influence exercised by the friendly societies cannot possibly be overestimated' while another argued that 'the political liberty of Western Europe has been secured by the building up of a system of (these) voluntary organisations..' But even to British observers the enthusiasm late last century in the Australian colonies for 'mutual aid' and for 'the forms and ceremonies' of what some knew as 'Oddfellowship' seemed 'excessive'[38].Before the First World War half or more of the population in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania were directly benefitting from friendly society services, as were more than 40 % of New South Welshmen. And even in the more sparsely populated States of Queensland and Western Australia, between a quarter and a third of the population enjoyed friendly society services.

Kincaid has written that in the early years of this century British politicians trembled before the political influence of the friendly societies and the insurance companies (and that) State-run social security was only possible because of the increasing financial difficulties of friendly societies from around 1900.

I'm still gathering material for the Australian version of this, but by eventually breaking the strength of friendly societies the BMA/AMA in the 1920's 'achieved its aim of the right to control the conditions of medical practice and established fee-for-service as the mode of medical treatment henceforth.'[39] Having adopted a State-oriented ideology Labor power-brokers did not contest this by supporting the friendly societies, rather they argued the result was one more proof of historic inevitability. And that the practice of State-welfare was theory-driven.

The first ALP Premier of NSW, JT McGowen, in fact introduced old age pensions in his State because his experience in a friendly society had taught him mutuality plus saving was a good idea. He recognised the inherent vulnerabilities of 'benefit societies' but what he forgot was the need for personal responsibility within the collective. As it happens McGowen was also a thorough-going Freemason and was one of the labour stalwarts who made it possible for Lord Carrington, State Governor and Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge in NSW to lay the foundation stone of Sydney's Trades Hall in 1888.

Many histories will tell you that Lord so-and-so laid the foundation stone of this or that, but won't tell you that the ceremony was actually conducted in what we might call the 'masonic' form, even when no Freemasons were there. It wasn't simply the Freemason's social status that brought this central role about, nor their usually being given credit for the bundle of ideas and practices referred to here. The Order had a great interest in benevolence and the transmission of cultural values, but in addition, and its story has to begin with it being regarded with great suspicion by British establishment figures for its Jacobin leanings.

All lodges, today, are in decline, and the loss of membership of 'trade unions' is just one part of that. At a time when Australian mateship is being denigrated and generational dysfunction is widespread, there is little awareness of what used to tie communities together, what 'solidarity' can mean or how the 'labour movement' built itself in the first place.