Sea Change - an essay in Maritime History by Rowan Cahill |

By Rowan Cahill

Published as a pamphlet in 1998 by Rowan Cahill Lot 4 Tulloona Avenue Bowral NSW Australia 2576

A very moving and sympathetic account of the life of a "working class hero" - Long time Seamen's Union Secretary (1941-1978), Eliot V Elliott (1902-1984). Elliott steered the Seamen's Union of Australia through the difficult changes in technological development in seafaring during the post war decades of the twentieth century. He was both forward looking and dedicated to the interests of seamen, in Australia and internationally. The Seamen's Union of Australia (SUA) in 1993 amalgamated with the Waterside Workers Federation (WWF) to form the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA), which was involved in a bitter dispute to defend jobs and conditions in 1998 against a conspiracy involving Patricks Stevedores, The Federal Government of Australia, and the National Farmers Federation.

Related Links: |

Sydney, November 30, 1984. Mid morning; a fine sunny day. The funeral cortege left from the Sussex Street Federal office of the Seamen's Union of Australia (SUA) and headed down Kent and Napoleon Streets for the wharf area and the shadows of the Harbour Bridge, known to old maritime workers who used to scour the area in search of jobs, haunted by spectres of unemployment and employer victimisation, as the Hungry Mile.

We walked six abreast, two city blocks long; the family, hearse, and SUA officials led the procession; the Union banner and the Merchant Navy flag preceded. The union was burying its dead; E.V. Elliott, Federal Secretary of the SUA, 1941-1978, a waterfront legend, had passed on. But before his coffin slid through the panelled wall of the crematorium chapel to the strains of the Internationale, we intended to symbolically escort his body to the scenes of the bitter waterfront disputes and human suffering that had, during the 1930s, torched within a young stokehold fireman the desire to change the nineteenth century seagoing conditions of his comrades on the Australian coast. [1]

Walking with me were seamen old and new; veterans who had lived through the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, some of them with lives that could fill novels; men who had gone to sea as boys, rounded the Horn under sail, ran fascist blockades in the Spanish Civil War, manned the North Russian Arctic convoys to Murmansk and Archangel; others who had helped save Australia during World War 2 when, as members of the merchant marine, they faced the daily hazards of mines, torpedoes, and strafing in Australian waters and over 200 of their comrades were killed; survivors of shipwrecks, and incredible lifeboat and raft voyages; quiet and modest men who did not regard themselves as anything out of the ordinary, simply toilers of the sea; and alongside them, adolescents starting out on their seafaring careers.

There were tears, and memories. And as we moved towards the wharves the colourful names of the pubs and boarding houses, once so well known to seafaring wanderers, meeting places and surrogate homes long since gone, replaced by soulless rnonoliths of glass and concrete and the ubiquitous parking lots, tumbled from the sharply etched memories of the old hands, names that had helped make Sydney one of the world's exciting seaports - the Blow George, the Bunch, the Big House .....

Obviously some of us were moving in our imaginations through a Sydney of ghosts, and even though momentarily I could see through their eyes that old Sydney, for I am young enough to remember a time in the 1950s when there were trams in the city and the now puny AWA tower dominated the skyline, I realised that was all in the past, and that up front in the flower swathed hearse was the corpse of one of the last union heroes.

But more than that, for as I walked it occurred to me that Elliott's death marked, symbolically, the end of the heroic age of Australian maritime history.

That night I realised few people would grasp the significance of the event. The biggest funeral procession in Sydney for years, equal at least to the turnouts for Prime Ministers, war heroes, and Premiers, yet nothing on the television news, even though the occasion had been filmed. Par for the course; history has a habit of ignoring seamen.

My relationship with the Seamen's Union, and union boss Eliot Valens Elliott, began by chance in 1970 when economic historian Ken Buckley approached me on behalf of the SUA to write up its century of history (1872-1972); my brief was to continue a manuscript commenced in the early 1950s by the late Brian Fitzpatrick (1905-1965). The prospect of the task was exciting; utilising my self taught journalistic, and recently accredited B.A. (Honours) historical, skills, I was to produce a quick job of research/ writing in time for the SUA centenary celebrations. Important also so far as I was concerned was the financial arrangement - a journalist's wage over a two year period, an offer that appealed to an unemployed, recently married, graduate. [2]

Some New Left and communist comrades were not impressed. At the time I was prominent in the student radical and anti-war movements, a contributor to Tribune, and a member of the editorial board of Australian Left Review. I was cautioned about becoming involved with the seamen. Dark rumours about Eliot were knowingly hinted to me across the coffee tables of the Sydney University Union Refectory and in the Day Street Tribune office; tales of violence, standover tactics, and corruption. And if this was not bad enough, the union's leadership was comprised mainly of dyed in the wool hard line Stalinists. So far as my future was concerned, whatever that "future" was, professionally I would be wiser to give the SUA a wide berth.

Such warnings had a perverse and opposite effect. Buoyed by my trust in Buckley and our close relationship forged in the anti-war movement I resolved to meet E.V. Elliott, albeit with some trepidation. In my mind I had formed a picture of the man, a sinister blend of late night television movie fare, a mixture of Humphrey Bogart, Peter Lorre, Boris Karloff and Edward G. Robinson.

Upon reflection in later years I concluded the image was to some extent one the man had "cultivated", not deliberately but by default. He was a tough man; he had lived a tough life; the image was one that had grown out of his youth, and once attached he had not worked to destroy it, for politically the image was an asset in an industry traditionally associated with tough men, seamen and shipowners alike, particularly shipowners and their fixers who masked their reality as licensed pirates with gentlemanly veneers. [3] During the Elliott era a lot of industrial negotiation took place in waterfront pubs where the talk was earnest, tough, and where the communality and loyalty of the waterfront ensured confidentiality. Their negotiators could match each other eyeball to eyeball, threat for threat if necessary, until understandings were reached and deals struck.

Over a spicy meal at one of Goulburn Street's Spanish restaurants I first encountered Eliot, and instead of an ogre met a handsome, quietly spoken, smallish, white haired sixty eight year old, sporting a white Lenin style goatee. Occasionally given to stuttering he came across as urbane, civilised, possessing a marked sense of humour, and direct - direct to the point of abruptness, but not to be confused with rudeness.

He was accompanied by his partner Kondelea, generally known as Della, a charming, perceptive person with whom I became close, one of those people who have contributed a great deal to the history of this nation in her capacity as an organiser, worker, and confidante to some major Left figures over the years, but who, because she was a woman and tended to work behind the scenes out of the limelight, has become one of "the legion of the overlooked", part of the forgotten tapestry of our social history.

The Eliot-Della partnership began in May 1951 during the New Zealand wharf strike when they worked together coordinating and distributing union donations in support of the New Zealand strikers; some of this money was smuggled across the Tasman via the motor vessel Wanganella. At the time Della was secretary to Waterside Workers' Federation (WWF) boss Jim Healy. In solidarity during the 151 day strike, Australian wharfies refused to handle cargoes from New Zealand. The Sydney and Melbourne offices of the WWF and the SUA were raided by police, and Healy was charged under the Crimes Act for hindering trade. The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) believed the New Zealand strike was part of a Moscow orchestrated campaign to disrupt waterfront activity in Australia, New Zealand, and on the American West Coast. This was the second time Della had been involved in a clandestine funding operation; in defiance of Commonwealth legislation that froze union bank assets, she was responsible for the safety of 8000 pounds worth of donations to coal field strikers during the 1949 Coal Strike.

An aside here relating to another clandestine matter; in 1954 during the Petrov Royal Commission, such was the hysteria generated by the Menzies Government and the mass media that the personal safety of one of the Commission's targets, journalist Rupert Lockwood, was threatened. When he had to travel between Melbourne and Sydney to appear before the Commission, the Victorian Branch of the SUA arranged a car, and shotgun armed escorts; had the personal liberty of Lockwood been threatened by any legal action as a result of the hearings, there were SUA contingency plans to spirit Lockwood across the Tasman. [4]

Della: family name Xenodohos (changed for Australian usage to Nicholas, based on the father's first name); one of four children; Greek migrant father - from Queensland canefield worker to King's Cross cafe proprietor; Australian born mother - background in many jobs, including circus performance; parental political sympathies - Left.

Born not long before the demise of Russian Tsarism, Delia left school at 14, trained as a shorthand typist and joined the workforce in 1932.

Active in communist youth activities, she joined the Communist Party during late adolescence.

Due to limited opportunities for office employment Della found work as a "lady's companion", involving cleaning, washing, and cooking; she also obtained some waitressing work. When office work was eventually secured it was with a succession of Left organisations - the International Labour Defence, Friends of the Soviet Union, the Militant Minority Movement.

Active in the NSW Branch of the Federated Clerks' Union since joining in 1936, Della was elected to the Central Council (1940), elected as an organiser (1942), and in 1943 became Assistant Secretary, the first woman in the union's history to hold high office. She held this position until resigning in 1948 for reasons of 'ill-health', in reality internecine left wing union politics. Commenting at the time upon Della's career, the union's journal The Clerk noted that "since her election ... she has become recognised as one of the leading personalities of the Trade Union Movement".

Della's special interests were the status of women and the issue of equal pay for women, both of which she pursued tenaciously as a delegate to the NSW Labor Council during the 1940s, and as an ACTU delegate in 1945 and 1947. She was successful on Labor Council in having policy on equal pay laid down. And in September 1947 at the ACTU Congress, successful in moving the first resolution to set forth a positive action programme for the equal pay campaign, giving life to paper decisions.

Having relinquished her executive position with the Clerks' Union, Della maintained her association with the union and remained a delegate to the NSW Labor Council. She was also prominently involved with the Trade Union Equal Pay Committee, established in 1946 with Jessie Street as Chairman. Della served on the executive of this active outfit from its outset - Committee Member 1946; Acting Joint Chairman January 1947 in the absence of Jessie Street; Joint Secretary from October 1948; Secretary 1949-50.

Along with union involvement Della was prominently involved throughout the period, and subsequently, in progressive campaigns and organisations, for example Sheepskins for Russia, the League for Democracy in Greece, the Union of Australian Women.

During the late thirties Delia commenced working for the WWF, and was in charge of its office for many years when Jim Healy was General Secretary. In 1955 she moved to the SUA, working on the Seamen's Journal as a journalist, and later organising the Federal Office. She worked in these capacities until her retirement in 1989. During this period the Journal became an important and indispensable membership forum, each monthly issue publishing a wide range of rank and file letters, articles, and discussion pieces. [5]

The Seamen's Journal, from its rebirth during World War II (after its demise during the disastrous 1935 Strike) until its last issue in May/ June 1993 (on the eve of the SUA's amalgamation with the WWF to form the Maritime Union of Australia), was lively and interesting; it was not the sole preserve of the union's leadership; it was actually read, discussed, argued over and enjoyed. It had a sense of community and camaraderie, and there were shared understandings quite often lost to outsiders. It was, to coin a term from modern management parlance, "owned" by the membership.

Indeed the volume of membership contributions consistently outweighed that authored by the union's leadership. By the late 1980s approximately a third of the total Journal was being written by an average of 20 seamen per issue. As one SUA veteran reflected, "it (the Journal) opened itself to our rank and file by encouraging them to write, write, write: 'sing the blues', complain, criticise, praise but don't remain mute with something stuck in your craw that only floats free with a beer; but put it into print so all can debate it. "

Eliot advocated the fundamental principle, at least from 1937 onwards, that "The printed word is the best organiser"; throughout his trade union career he gave high priority to the role of the trade union journal. [6]

During the time I worked for the SUA (1970-72), I heard numerous backhanded compliments about Della's abilities. Critics of the union liked to suggest nastily that she was in fact the power behind the ageing Eliot, a poisonous misrepresentation of a loving relationship, yet tacit recognition that the couple functioned as a team. Eliot the union boss, Della his partner, confidante and sounding board. As I came to know the SUA I realised there had been another such team, Federal President Tom Walsh, "the Lenin of Australia", and his wife Adela Pankhurst Walsh (who also worked on the Seamen's Journal), in the heady decade of the 1920s when Australian seamen were depicted by conservative forces as bolshevik lepers of the sea lanes, a time when Tom and Adela were heroes of the Left, years before they became entwined in the neurotic skeins of the far Right. [7]

So it was I began my research, at a time when little work had been done on the Australian maritime industry. John Bach's comprehensive A Maritime History of Australia (1976) appeared a few years after my labours had been completed. The first issue of The Great Circle, journal of the Australasian Association for Maritime History, was published in 1979.

Historians interested in the area tended to be concerned with company histories, or with ships. Captains were also important. However seamen rated little, if any, mention; the very people who had through their sweat, toil, and sacrifice, helped build this nation and its wealth had been left out of its recorded history. It was as though a ship amounted to little more than its owners and the officers, and of course the cargo.

A great deal of Australia's historical, economic and cultural development has been dependent on what has happened in its port cities and upon its seas. As maritime historian Frank Broeze pointed out (in 1987), along with the bush and cities, the sea (and the maritime professions and industries) "must be regarded as the third integral element of Australia's history." [8] For me, however, this point was best made by wharfie author John Morrison (1904- ) whose work I encountered in SUA bookcases. In his short story collections Sailors Belong Ships (1947) and Black Cargo (1955) one theme was precisely this, articulated in a literary context.. the relationship between maritime workers, the cargoes they load and ship, and the wealth their often exploited labours generate - for others.

In my stay with the SUA I came to see my task as not only the writing of the story of a unique union organisation, but of going a small way towards bringing seamen into the recorded history of Australia. As workers they deserved more than being smuggled into history at times of crisis (eg the Maritime Strike of 1890) and subsequently forgotten.

During the weeks that followed Eliot's death, in Sydney's Hornsby Hospital on November 26, I tracked down and read a novel he had once recommended to me as being the best about the waterfront; The Harbour (1915) by Ernest Poole (1880-1950), Pulitzer prize winning American journalist and novelist who covered the 1905 and 1917 Russian revolutions and first made his mark exposing the appalling conditions of New York's slums. In Poole's central character, Joe Kramer, knockabout socialist militant, I recognised the style and rhetoric and many of the qualities of the SUA leader .... courage, commitment, faith, blunt honesty, integrity, love for the working class, hatred of war, a socialist vision of a better future; and grit. And like Kramer, when Eliot spoke about socialism his wards came to life, and personally I felt I was not listening to a dream.

Reading the novel I felt close to the man again, and recalled the way an anti-union publication had once described him; as "a communist Robin Hood". There was something in that too, especially if with poetic licence you also tossed in a dash of the buccaneer.

In retrospect, it seems to me, there was a lot of "America" in E.V. In his younger days one of his waterfront nicknames was "The Yank", partially a reference to an American sojourn, partially to his voice which, because of a speech defect, sometimes produced an American style accent. Part of Eliot was very much at home in the world of Poole's The Harbour, a world that smacked of the passion, rhetoric, and visions of the Industrial Workers of the World(IWW). I hear him as well when I read Tom Joad's words about unionism and the spirit of the ordinary worker, towards the end of John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939).

There was an element of working class populism in Eliot, and I think this was part of his power and strength; his dreams could touch the dreams of working people. Also from Steinbeck's novel, I think he would have agreed with these words of former preacher Jim Casy; "a fella ain't got a soul of his own, but on'y a piece of a big one...."

Just how Eliot evolved politically, he never explained to me. As for early influences, one can surmise. Not long before adolescent Eliot went to sea, another youngster, son of a Melbourne realtor, commenced his maritime career on a ketch trading between Melbourne and Hobart - Harry Bridges, later to become one of America's most powerful union bosses as head of the West Coast International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union.

Before casting adrift from Australia in San Fransisco, April 1920, Bridges was radicalised within the context of Australian maritime labour. The General Strike of 1917 was crucial, as were shipmates who were members of the IWW. Jack London's The Iron Heel (1907) was a formative anti-capitalist influence.

American historian Bruce Nelson points to the international perspectives of Australian maritime workers, seamen in particular, and their "mood of syndicalism" in the first two decades of this century. He describes this mood as "militant, irreverent, 'on the job' ". While accepting that the question of "Ideological transmission" is "difficult and elusive", Nelson states it is clear that Australian militancy, particularly that of maritime workers, influenced American West Coast unionism. "Membership books in the Australian Seamen's Union and the Sailors' Union of the Pacific were interchangeable"; he mentions Australians who left their marks on West Coast maritime unionism-Harry Bridges, Henry Schrimpf, H.M.Bright, Al Quittenton, Harry Hynes.

And so we glimpse the culture that was part of the early SUA; part of Bridges' background, and arguably part of Eliot's.

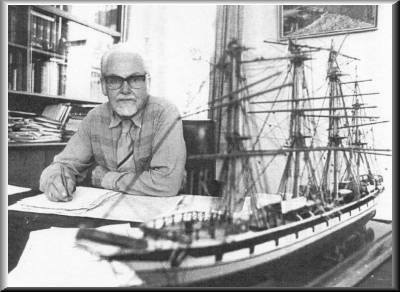

The paths of the two men would intersect decades later and they would work together. In 1971 I asked Eliot what he thought of Bridges. Eliot was working at his desk at the time; he raised his eyebrows above his glasses and looked up with a minimum of movement. An ominous sign. "Bridges?", he growled; then he grunted dismissively. Eyebrows lowered. Work resumed. End of topic. [9]

Eliot was born in New Zealand in 1902, son of Helena Elliott (nee Gray), age 18, and James Elliott, wheelwright, age 30. James either died, or otherwise left the family, when the boy was three; the man Eliot called "step-father" was killed in a mining accident twelve years later. The birth certificate records the future union leader as Victor Emmanuel Elliott; a study of his discharge papers shows he kept this name until December 1924 when he appears on the Largs Bay as Eliot V. Elliott. The circumstances of the name change are not, to my knowledge, known; it was not a matter he discussed. People who were close to him in the 1940s and 50s referred to him as Vic. [10]

It should be noted that circumspection regarding personal background was part of the culture of Eliot's generation of maritime militants, and of the industry generally for that matter. Name changes were common for many reasons - the need to circumvent employer victimisation; the desire to make a break with a shore based personal history; the needs of clandestine militant work. Researching the SUA history I met a number of seamen from whom I learned not to act like a biographical detective. I accepted a maritime tradition; judge a seafarer as a worker and comrade, and not on the basis of a past.

Eliot gained the New Zealand Department of Education's Certificate of Proficiency (Standard VI) in December 1917. A surviving academic record (November 1917) shows the youth had a flair for Drawing, above average English skills, and average attainments in Arithmetic, Geography, and History.

Leaving school soon after gaining this Certificate Eliot worked on the railways, first in construction work and later as a telegraphist, before going to sea. Whether or not he started out as a deckboy is a matter of conjecture. A damaged Federated Seamen's Union of New Zealand union book shows him as a member in 1919; discharge papers that same year record him as a trimmer engaged in the intercolonial (ie trans Tasman) trade.

By April 1921 Eliot was a fireman; he worked deepwater vessels from then until June 1925. In November 1921 he briefly became a member of the British National Sailors' and Firemen's Union, claiming 1894 as his year of birth. He worked the Atlantic run, and in interviews told me he was ashore for a while in the US, unemployed, and experienced doss house life. From others I heard stories of him being in jail during this period, though he only chuckled when I sought confirmation.

Records show him as a member of the West Australian Branch of the Seamen's Union in October 1922, a transferee from the New Zealand organisation, and registered as V.E. Elliotte. By early 1925 he was a shipboard delegate; in those days this role courted physical injury and employer victimisation. Eliot experienced both, and knocked up a reputation as a tough and cocky unionist. During the 1925 Strike he was ashore for over five months as local and international industrial politics chaotically and violently meshed, disrupting the maritime industry of Britain and its Dominions for over 100 days. [11]

Sometime during the 1920s, perhaps during this strike, Eliot was involved in the punting industry. Amongst his personal papers is a small white gilt-edged visiting or business card, in the name of Elliotte. Perhaps this card and the fancy 'e' were part of this persona. But then for a time in 1924 he signed himself Elliotti. Certainly the Elliott personas interested and intrigued the compilers of security dossiers over the years. [12]

By 1935 the New Zealander had become recognised as a leader of Australian seamen, and was prominent in the long, bitter, ill-fated strike that year (from December 1935 to February 1936) against an unsatisfactory Award and poor working conditions. The 1935 Strike, as it has become known, failed, and the union was left divided and crippled.

Earlier in 1935 we catch a glimpse of Eliot the thinker. In one of his few Letters to the Editor (Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 1935) he discussed the presence of Japanese whaling fleets in Australian and Antarctic waters. As a simple "worldly wandering seafarer" he asked why it was that foreign ships could be involved in enterprises and waters where Australian crews and ships could be, but were not. What was wrong with Australian "business acumen" he wondered. The questions he raised in the letter would be asked many times by Australian seamen through the years. A feature of Eliot's SUA leadership, post World War II, was the concerted effort to protect and extend the role of Australian seamen and ships in the import and export trades.

In 1936 Eliot was elected SUA Queensland Branch Secretary, and became a member of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) - an organisation in which he became a linchpin until 1971 when, following bitter ideological differences, he became a foundation member of the pro Soviet Socialist Party of Australia (SPA).

From Queensland Eliot took upon himself the task of rebuilding the union. To facilitate this he personally adopted a policy of as much face- to-face contact with the rank and file as possible, and created a journal, The Seamen's Voice, in which he hammered the themes of unity and solidarity amongst seamen and maritime workers generally, rank and file participation, organisation, and internationalism.

Following his election in 1941 as Federal Secretary of the SUA, Eliot quit Queensland and took office in Sydney. Together with fellow officials Bill Bird, Barney Smith, and Reg Franklin, he guided the union through the difficult war years and forged in the process a strong & united, militant outfit.

During the next 37 years with E.V. at the helm the SUA successfully improved the wages and conditions of Australian seamen and gave their job a security and dignity it had never had before. During the Cold War the union battled assorted reactionary forces with courage and vigour. Internationally it combated imperialist aggression, notably during the Vietnam conflict, with distinction. At every opportunity the union sought to assist in improving the wages and conditions of foreign seagoing workers.

Recognition of Eliot's role as an international trade union figure came in 1949 when he was elected Vice President of the Seamen's and Dockers Trade Department of the World Federation of Trade Unions. President was the Australian born American longshoreman Harry Bridges.

As a human being Eliot was a man of exceptional character, strength, and charm; he had the innate qualities of a leader. He was witty, and a raconteur worth listening to. Life, he told me, should be regarded as one long learning process.

In times of crisis Eliot remained outwardly unperturbed. He seemed gifted with the inability to panic. I witnessed this clearly in 1974, just before the Sweeney Royal Commission investigated SUA involvement in the imposition of levies on foreign ships which had participated "casually" in the Australian coastal trade on a special "permit" basis. That year the union had, along with other maritime unions, commenced a levy system, extracting from shipping interests involved the difference between the wages earned by the foreign crews employed on the "permit" vessels and the amount payable had the ships been manned by Australian crews. The money obtained was, where practicable, distributed to the foreign crews, or else deposited intact in the bank.

The levy was conceived as a form of penalty on the shipping interests involved for taking the low waged, cheap, often "flag of convenience" and sub-standard safety-wise, option. The SUA argued that the permit system threatened the livelihood of Australian seafarers; its attitude was that all coastal trade should be retained for Australian crewed ships, while the role of Australian ships in the overseas trade should be extended. [13]

When the levy practice became a matter of media and parliamentary speculation later that year, Cold War type allegations of SUA rorts, corruption, stand over tactics, and criminality surfaced. At a press conference held by Eliot immediately following the announcement of the Royal Commission, journalists tried to pursue these allegations.

Amazed by his self possession, adroitness, and humour in the face of hostile political questioning, I asked him afterwards where it all might lead. Bemused he replied: "Cahill", for that is how he always addressed me, "a moment like this holds dangers for the union, but provides great opportunities as well."

One only has to read his December (1974) evidence before the Commission to see what he meant. Expertly led by Assistant Secretary Patrick Geraghty, Eliot's evidence constituted an informed critical analysis of the Australian shipping industry, its history, failures, possibilities, potential, and future directions. The SUA used the Commission to air issues it had unsuccessfully been trying to bring into the national and public domains since at least 1952.

Self-effacing, Eliot never sang his own praises. Indeed during my researches I found the man infuriatingly modest. It was always "my colleagues and I." This same characteristic was a feature of his successor as Federal Secretary, Patrick Geraghty (1979-91). [14] This reluctance to accept the accolade of greatness, and the insistence on seeing oneself as part of a team, as one who fronted for the collective efforts of many, was not a false modesty, but very much a seafaring attitude. A well found ship, after all, is only as good as its crew.

Amongst seamen Eliot was, in his later years, many things ... patriarch, friend, adviser, mentor, surrogate father, and legend. He inspired love and loyalty and did not seem to harbour grudges. Commenting on seamen who scabbed during the 1935 strike, a couple of whom later disappeared at sea having been lost overboard, a euphemism that masked grimmer realities, he told me of the close relationship he later had with some of those who crossed the picket lines. "You've got to understand what motivates people, and learn that people can change; you've also got to understand the forces that made men cross the picket lines in the first place, " he stated emphatically.

Change was something I too experienced. I came to the SUA a product of the 1960s, a New Left radical, in part an elitist, youthfully arrogant towards older comrades, convinced that me and my kind were the catalysts of social change and also the embodiment of wisdom. I left the seamen having met amongst their ranks artists, maritime historians, poets, short story writers, raconteurs, musicians, singers, men who could turn rope and wire into works of art - skills mastered in the last days of sail; I met new teachers, and I left humbled in the best sense of the word, wiser about the world and people, aware that I had only commenced on a life of learning.

A further legacy of my sojourn with the seamen was that I came to understand in a personal, as opposed to theoretical, sense the tremendous contributions workers generally have made to the development of Australia; that they are in a very real sense its heart and soul.

Some things stand out, like sharing a meal in the mess room of the old Iron Monarch in 1971, discussing with seamen the novels of George Johnston, and later browsing through their shipboard library of 500 volumes, the latest addition being the complete works of George Bernard Shaw. It was a seamen too who introduced me to the works of the philosophical anarchist novelist B. Traven, in particular The Death Ship (1940) - "if you want to know what life at sea was like, read this," long before Traven became the subject of a lively literary industry. [15]

Criena Rohan in her novel The Delinquents (1962), set in the 1950s, has as a central character a young Australian seaman. Rohan writes of the library on his ship as being full of lurid historical fiction; "lusty busties" is her descriptive term. True. But there were also libraries like the one I mention. Before the advent of shipboard television, mess room bars, and quick turn arounds in port, serious reading was very much a part of shipboard life. [16]

When critics and enemies spoke about Eliot, it was with a grudging respect. [17] No one could deny the loyalty seamen showed him, nor the profound influence he had on the union. As I came to know the man I realised there was no mystery in any of this, merely hard work and skilful management; it was not just for nautical semantics that his personal page of comment in the Seamen's Journal was titled "ON COURSE!"

To explain Eliot's longevity as a union leader and his influence, the following points are relevant:

Eliot as Federal Secretary also practised this style, one he had forcefully articulated and developed during his leadership of the Queensland Branch during the late 1930s.

Furthermore any seaman could, if he wanted to, if he had something on his mind or something to query or report, find his way easily into any official's office, without hassle, often without appointment. The SUA leadership generally prided itself on its contact with the rank and file. After all it was not a big union (3699 members in 1969; 4517 members in 1977), and its size permitted and enhanced informality, fraternity, and communication.

These men were mostly veterans of the 1940s and 50s, some of them ex servicemen, with an awesome collective background of war and political struggle. Yet it was a background that was in tandem with an urbane worldliness, wit, intellect, and humour. They were men who took their seamanship seriously, regarding themselves as highly skilled workers, indeed craftsmen, who thought of themselves as being part of a seafaring continuum that reached back and deep into history. They tended too to have hobbies in dying maritime arts - like ship modelling, wire and rope weaving, shanty singing, folk lore collection, story telling.

Apart from being Eliot's eyes and ears around the nation, to these men were entrusted important SUA, and sometime CPA, missions nationally and abroad, the initiation of new union policy, sometimes the discrete sorting out of contentious shipboard troubles.

In terms of political reality this group was a cadre force, characterised by a common maritime and political culture. It did not remain static as people variously left the industry and younger members joined, though there was an identifiable stable core. From its ranks too tended to come the union leadership during the long incumbency of Eliot. Veteran Newcastle Branch Secretary (1953-87) John Brennan identified the creation of this force as one of the major achievements of Eliot's leadership. As Brennan explained in 1984: "That force will subsequently come up from behind all of us when we retire or die and keep the Union the great organisation it is..." [18]

The existence of this cadre force helps explain the cohesiveness of the union, the absence of the sorts of internecine politics that crippled some unions during the Cold War years and through to the 1980s, the stability of the union's leadership and the continuity of policy; officials and policies in the SUA did not come and go according to turnstile factional whims.

The term "Stalinist" conveys a sense of an "enclosed Marxism", to coin an E.P. Thompson term[19], and certain emotional attachments. Beyond that, however, it is of little value, for when it comes to local unionism and industrial relations it says little about what happened historically in the context of Australia. And if the term is also meant to convey a general sense of fossildom, then in Eliot's case it was wide off the mark.

One only had to see the 70 year old man at work to know there was nothing dated about him nor out of step with the industrial times. I sometimes wonder to what extent his critics in the 1960s and 1970s were expressing ageist, rather than political, attitudes when they called him a Stalinist.

Each working day for Eliot, when I knew him, began with the ABC radio news; then he scoured the, Sydney Morning Herald, the Daily Telegraph, the Australian, and the Financial Review; Hansard was daily fare, while his desk, office chairs, and a reading lectern, were neatly piled with law reports, government reports, shipping company annual reports, as well as local and overseas trade union and communist journals, Tribune, and the Australian journal of Labour History - all marked, underlined, asterisked, read, digested.

Sure, Eliot's roots were in a time when sail and steam could be seen together on the waterfront, and the exploitation of maritime labour was crude and blatant; a time when seamen worked long hours for low wages, slept in crowded fo'c'sles that served as their sleeping, eating and recreation areas, and when serious accidents and death were part of maritime life; an era of crowded habourside pubs and cheap rooming houses, when the term Wobbly still meant something, and the Russian Revolution was young and offered hope for the future; an era when industrial and union issues could be settled with fists and knuckle dusters, and firearms were not strangers in debate.

As I look back, this was the singularity of Eliot. Hs fire, in a sense his politics, were from another era; but he was modern too, and his modernity was always conscious of the past. I think it is this that most explains the aura of authority, and legend, that surrounded the man.

In the labour movement, Eliot once told me, one found two sorts of leaders - both essential; those who, like a comet, came apparently from nowhere, flashed briefly across the industrial sky fighting for working people, and in this context he mentioned the role of Pat Mackie in the 1964/5 Mount Isa Dispute; and those who, like the Pole Star, were constants, setting a course by which to steer. And he left it for me to figure out he was numbered amongst the latter.

The modernity of Eliot is evident in the SUA reaction to technological change, a feature of his era as Federal Secretary.

During the 1950s and 1960s the face of Australian shipping began to change, slowly at first but accelerating through the sixties. And the SUA had to deal with it. Factors like competition from rail and road transport, the ageing nature of the Australian merchant fleet (in 1954 the Australian carrier fleet of 128 ships contained 72 vessels over 25 years old), the huge costs involved in modernisation, caused some of the great name shipping companies, like the Melbourne Steamship Company and Huddart Parker, to disappear, while others merged to form new companies (for example Adelaide Steamship Company and McIlwraith McEacharn Ltd merged in 1963 to form Associated Steamships).

In the process of fleet modernisation new technologies impacted on the Australian coast - bulk carriers, roll-on roll-off ships, container vessels, tankers, all appeared during this period. The rapidity of change was reflected by the growth of the tanker fleet. One in eight ships trading on the coast in 1969 were tankers; five or six years previous tankers were a new type of ship to Australian seamen.

Australian shipping interests warmed to technological change and became pioneers and innovators in the field internationally, constructing, for example, the world's first new built container ship (as distinct from the conversion of existing ships), pioneering roll-on roll-off technology, and in the forefront of adapting the industrial gas turbine to marine propulsion. [20]

Along with new types of ships came other changes. For example as the sixties drew to a close, spray on and roller applied epoxy coatings on decks and superstructures were in use which, along with the elimination of masts and derricks, and the advent of shipboard cranes and hydraulic hatch covers, eliminated or reduced labour intensive maintenance and operations work done by seamen. The introduction of the locked engineroom, where crew were no longer needed in the engineroom overnight, further changed traditional shipboard work practices.

With new and converted ships came moves by shipping authorities to reduce manning levels and introduce general purpose manning and integrated crews.

During the second half of the 1960s the offshore gas-oil industry was developing, bringing with it attendant injury and loss of life, vessels not under the jurisdiction of Australian maritime law and supervision, and creating opportunities for SUA coverage and job expansion. [21]

Change was a feature of rank and file and Seamen's journal discussion; it was a feature of discussions by the leadership; it was a topic of conversation on the ships, and in the pubs and haunts of seamen. Which is not to suggest there was not also incomprehension, hostility, and resistance. But like it or not change was taking place locally and internationally.

The effects of change in the seagoing industry were so obvious and blatant they could not be ignored, and the SUA was small and cohesive enough for this realisation to diffuse through the ranks. The hard- headed reality was that technological change had come to Australia, and every indication was that it had in a sense only begun, that it would keep on coming and escalate.

The problem had been comparatively simple in the early 1950s when technological change was referred to as "automation" and "rapid mechanization". Three unions had borne the brunt of this change - the SUA, the Waterside Workers and the Miners. These unions had histories featuring militant traditions and actions in support of one another. In their executives and memberships the Communist influence was strong. Collectively, in advance of the rest of the union movement, they faced the future in a trail blazing role, often sharing the experience of having to do so. In the beginning the problem was seen as trying to stem the extent of job loss and demanding benefits like extra leave and shorter working hours in an attempt to get a greater share of the benefits produced by higher productivity resulting from technological change. [22]

However for the SUA the crunch came with the commissioning of the Australian built and taxpayer subsidised (to the tune of one million pounds) Ampol tanker P.J. Adams in 1962. From the date of commissioning until 1966 the ship traded with a low wage foreign crew. Eventually after a long, bitter and tenacious campaign that galvanised the rank and file, the union put an Australian crew on her under Australian award and manning conditions.

But the struggle added a more fundamental dimension to technological change so far as the SUA was concerned. It was obvious that technological change meant more than just job loss and changed work practices. The P.J. Adams affair demonstrated symbolically that technological change could, while leaping forwards in one sense, in another constitute a giant step backwards to industrial and political scenarios reminiscent of the nineteenth century. The SUA could well end up a casualty in the process, the ranks of seamen decimated, and those remaining in the industry subject to any exploitative whim.

It did not have to be like this and the SUA took up a term and argument that had been used in European maritime and trade union circles since the mid 1960s and extensively discussed by the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU), an organisation the union had long been intimately associated with.

The term was "social progress" and the argument went that technological change, while increasing productivity, should produce fundamental social benefits for workers affected, be they directly involved with the changes or displaced by them. The emphasis was on fundamental. Following European models, for the SUA it entailed involvement in the process of technological change in a consultative way if possible, militantly if necessary, with a view to minimising adverse impacts, and fundamentally changing the ways in which seamen lived out the totality of their lives. [23]

In June 1968 the union's policy making body, the National Committee of Management (COM), met and over four days hammered out a historic document formulating the union's attitude to technological change on the basis of social progress.

What the COM drew up was a program for the future in the form of a list of demands of what seamen wanted in exchange for their making the necessary sacrifices and adaptations demanded by technological change. At the same time the union was serving notice that technological change in the maritime industry, so far as seamen were concerned, was not going to be a linear lock-step determinist process but rather a social process with the union actively intervening for human and social goals.

The five point plan called for improved shipboard accommodation; increased wages and benefits on ship and when ashore (including an aggregate wage); reduced hours of work and increased leave provisions (which included regulated leave, and an extension of the swinger system); improved social conditions, including retirement and superannuation rights and entitlements similar to shore based workers; vocational training for new entrants to the industry, with retraining and educational opportunities for existing personnel to meet changing conditions and facilitate career development.

Viewed as a package the claims were radical in the sense that the benefits sought included ones historically denied to seamen generally - Jack London's "peasants of the sea". Implicit were the propositions that seamanship is a skilled craft, and not something that can be done at anytime, by anybody; that all seamen have the right to be able to plan for a normal family and home life, and not have to spend their lives within waterfront orbits and traditions of makeshift accommodations and transitory relationships - the "fo'c'sle or the streets" syndrome; that seamen have the right after a hard working life to retirement, and dignity in retirement, and should not have to keep going to sea for as long as possible then eke out an existence in the loneliness of pub accommodation or on caravan park back blocks.

My use of the word "historic" in this discussion is deliberate, and the nine men who comprised the COM deserve recognition - John Benson, John Brennan, Des Dans, E.V. Elliott, Jack Fitzgerald, Pat Geraghty, Ron Giffard, Burt Nolan, Snowy Webster; for during the four days of intensive and complex discussions they achieved what few other Australian union leaders had, that is accept the fact of technological change, formulate a fundamental response to it, and have the confidence and nous to expect to be able to bring this successfully into the ambit of industrial relations.

Unanimously endorsed by seamen at Australian wide stop work meetings towards the end of June 1968, the COM program officially became SUA policy. The following year it was published as a four page leaflet for general distribution outside the union where some seamen of the time recall it being perceived as "eccentric policy".

By 1992, the year prior to amalgamation with the WWF and the consequent formation of the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA), the social progress claims had by and large been achieved, the 1968 COM in effect having broadly set the union's agenda for the following two decades.

Back in 1968 Eliot had explained to seamen that they had "to take advantage of technological developments", and "the future belongs to us if we learn how to grasp and hold it". He emphasised: "We believe men are more important than machines and new ships." [24]

The future belongs to us; those were the words of a veteran socialist who had knocked around the world's ports since the 1920s, words refreshingly alive at any time of history. They were also the words of a person who understood that progress should be a three way dialogue involving the past, present, and future.

One night, not long before he died and he knew he was on the way out, I visited Eliot. He was lying on his bed propped up on pillows, no pyjamas because that was a sign of convalescence, wearing his gardening trousers (he loved to garden, was proud of his vegetable crops, and grew his own bamboo garden stakes) and a red checked heavy shirt, the sort he had worn in the stokeholds of his youth. Contrary to Hollywood depictions, men who directly stoked the steamship furnaces did not do so naked to the waist; a heavy shirt was almost mandatory to protect the body. And periodically the men had to recuperate under the ventilation shaft, hanging onto straps suspended across the shaft outlet to facilitate their breathing.

Eliot's mind wandered as we talked and in his imagination he went back to some time in the distant past, I could not figure when, the early twenties? after the 1935 Strike?, just him and a mate, unemployed, seeking work, on foot, tramping a coastline between ports, morning, the sun rising, a glorious dawn that lived in his mind. The two men sat down in the lush green grass of that past, relaxed, and watched the day rise out of the sea.

He spoke with an occasional quiver and stutter interrupting the lyrical flow of his voice, and eventually tailed into silence as he listened to his own inner voices; his eyes seemed to shine and a ghost of a smile played on his lips.

They were the last words I heard from the man; in retrospect, I think, the metaphors of an old socialist, recalling for me the last paragraph of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, the 1914 socialist classic by Robert Tressel I'd encountered via a review in the pages of the Seamen's journal:

"But from these ruins was surely growing the glorious fabric of the Co- operative Commonwealth. Mankind, awaking from the long night of bondage and mourning and arising from the dust wherein they had lain prone so long, were at last looking upward to the light that was riving asunder and dissolving the dark clouds which had so long concealed from them the face of heaven. The light that will shine upon the world wide Fatherland and illumine the gilded domes and glittering pinnacles of the beautiful cities of the future, where men shall dwell together in true brotherhood and goodwill and joy. The Golden Light that will be diffused throughout all the happy world from the rays of the risen sun of Socialism."

During the morning of April 12, 1985, the MT Robert Miller hove to south east of Sydney Heads, and a mariner's funeral service was conducted. The ashes of E.V. were then scattered on the sea. But only part. The rest remained on land. It was in accordance with his wishes, and as it should have been; for he was of land and sea.

For me the death of Eliot symbolically heralded the end of an era; and less than nine years later, by way of confirmation, the SUA ceased to exist following its merger with the ~ to form the MUA. But that is all it was; the end of an era, not the end of history.

I have lost count of the number of times futurologists have tried to convince me of a technologically gee whiz future, one in which we will feel alien unless we immerse ourselves in the culture and accoutrements of microchips and megabytes, a future in which the knowledge we already have does not apply, and in which few of the lessons or experiences of the past are applicable; a future in which present skills are irrelevant and in which history finally comes to rest.

I see a different future. Its shape is suggested by factors like the pollution clouds that choked much of South East Asia in late 1997; ongoing corporate vandalism in our planet's Amazon Basin lungs; resurgent nationalism and ethnic animosities; resurgent Islamic and Christian fundamentalism; resurgent Astrology; global looting by corporations, the same corporations that threaten, internationally, notions of democracy and citizenship; the backwards march of working conditions to a Dickensian past; the normalisation of immisertion as an economic policy; the ever increasing gap between rich and poor, globally and within Australia; the increasing retreat of the rich into fortress enclaves; the deadening of the human spirit by consumer materialism. Much of this is very familiar territory indeed.

In the maritime industry internationally, rust buckets and death ships ply the sea lanes, while some get to trade in Australian waters. Half of the world's commercial vessels fly flags of convenience, thus circumventing taxes, safety and health regulations, unionism, and human responsibility generally. An estimated 1.2 million seafarers, three quarters of them Third World workers, move more than 98% of world trade. While generating huge profits for often anonymous owners who hide in complex financial and corporate mazes, the majority of today's seafarers are subjected to conditions that were common in the days of windjammers - physical punishment; work related injury and death; unhealthy food, water, working conditions; poor pay. Collectively these phenomena eventually impact upon Australian maritime workers, threatening hard won conditions.

Elsewhere maritime insurance rackets and scams known well to seafaring victims generations ago are again part of maritime life. Piracy resurges on a global scale, but particularly in Asian waters; 500 reported incidents during the 1980s; a multi million dollar criminal industry bold and strong enough to harass major flag shipping, including Australian vessels. [25]

Forces similar to those which led to the SUA being forged in 1872 out of a series of meetings in waterfront hotel and church halls, are again part of maritime experience.

We head towards a future in which the chronological clock moves forward, but the human and political dimensions move otherwise. While conservative voices urge the end of unionism as part of the future new world order, the need for unionism insistently remains-to hold on to what has been built and gained during long years of struggle, and in tandem with socialist perspectives and hope, to work for a future in which opportunities for social justice and human emancipation are maximised. [26]

Not long before his death in 1947 the Hungarian sociologist Karl Mannheim, once a refugee from Hitler's new world order, discussed the post-1945 new world order. He argued that in a society where political democracy was allied with a competitive economy based on private property, the profit motive, and the life-and-death struggles of the market place, and where the gap between the haves and have-nots increases and people come to believe only in power and violence, "anticipating aggressiveness and dominating behaviour in others" while reverting to it themselves. and where notions of the redistribution of power and wealth go out the window, then contamination would follow, the process leading to fascism - a dated term perhaps in this era of cyberspace and post modernism, but the message is clear and real enough.

His words resonate across the decades and should serve as a warning as the voices of post-Cold War reconstruction talk of a new world order, one based on market forces, the "level playing field", privatisation, and policies which cynically lead to increasing gaps between the haves and have-nots, and which see social justice through the prism of economic imperatives and the principles of managerialism and utility.

In a very real sense the ultimate challenge we face today as trade unionists is no different from that which confronted trade unionists at other turning points of history and which some unions, like the SUA, pursued with tenacity for much of this present century; how to create a better world and construct a more equitable and just society for all. The failure to accept this challenge, or even to countenance it, can but lead to a social system and world best described, to coin a Mannheim metaphor, as "a pitch-black night." [27]

For the resignation and career comment, The Clerk, March 1948, p.9; the politics of the resignation were outlined to me in an interview with Della, 19 January 1995. The M.J.R. (Jack) Hughes papers, University of Western Sydney, Macarthur-Library, were helpful in piecing together Della's career in the Clerks' union. An outline of Della's equal pay activities is in The Clerk, October-November 1949, p.11. For the resolution see ACTU Congress Minutes, 9th Session, 5 September 1947, p.4. The Trade Union Equal Pay Committee Minutes, 1946-50, yielded Della's involvement with this organisation.

The personal papers I refer to in my text are in the possession of Mrs. K. Elliott, Roseville, NSW. They include Elliott's birth certificate, some education records, his union books and discharge papers.

Rowan Cahill is a graduate of the universities of Sydney and New England. He has worked as a teacher and freelance writer, and in various capacities for the trade union movement as a rank and file activist, delegate, and publicist. Author, or co-author, of four books and numerous pamphlets, Rowan's writings have also been published in a wide range of academic, socialist, and radical publications.