Not long after he joined the I.W.W. Tom Barker was appointed national organiser. He travelled south to Wellington and after several meetings around the docks and the railway workshops a branch was established. In Christchurch he was arrested for selling literature and fined ten shillings. He stayed in Christchurch for about a month and once again a branch was re-organised. Then on to the West Coast mines where he no doubt met Ted Hunter, a Wobbly organiser, miner and musician. Hunter wrote a regular column for the Maoriland Worker under the name "Banjo Hunter". The nickname "Banjo" could relate to either the banjo shovel used by face workers or the musical instrument. On the eve of the strike, in October Barker was back in Wellington speaking at the Post Office square. In the same month the Huntly miners went on strike and were promptly locked out by their employers. In Wellington the watersiders struck over travelling time and the dispute spread to all the main ports and to the mines of the West Coast. Barker was asked to organise public meetings in support of the strike.

Not long after he joined the I.W.W. Tom Barker was appointed national organiser. He travelled south to Wellington and after several meetings around the docks and the railway workshops a branch was established. In Christchurch he was arrested for selling literature and fined ten shillings. He stayed in Christchurch for about a month and once again a branch was re-organised. Then on to the West Coast mines where he no doubt met Ted Hunter, a Wobbly organiser, miner and musician. Hunter wrote a regular column for the Maoriland Worker under the name "Banjo Hunter". The nickname "Banjo" could relate to either the banjo shovel used by face workers or the musical instrument. On the eve of the strike, in October Barker was back in Wellington speaking at the Post Office square. In the same month the Huntly miners went on strike and were promptly locked out by their employers. In Wellington the watersiders struck over travelling time and the dispute spread to all the main ports and to the mines of the West Coast. Barker was asked to organise public meetings in support of the strike.

'By relays of speakers, by I.W.W. songs which were catching on, we kept these meetings going continuously and at the same time we did not neglect the organising of the pickets. When the government brought in volunteer farmers as strike breakers the workers retaliated. The road into Wellington has steep gorges on one side and was fenced off from the sea by barbed wire. At night time when we got word from cyclists that the farmers were coming we would stretch this barbed wire across the road then get up on the hillsides and pry big stones down on them.... the farmers would make a dash for it and land up in the barbed wire, in many cases getting badly cut.'

Back in Wellington Barker relates in his memoir instances when the strikers attacked the specials barracks. Within a few weeks riots became continuous and the gun smiths were doing a roaring trade in the sale of revolvers. The police never caught on to this until all the guns in Wellington had been sold. However in Auckland all was quiet until November 8th when eight hundred farmer volunteers occupied the wharves armed with revolvers and pick handles. They also raided the offices of the Watersider's and tore down a banner from the front of the building which proclaimed "Workers of the World Unite. One Big Union".

Back in Wellington Barker relates in his memoir instances when the strikers attacked the specials barracks. Within a few weeks riots became continuous and the gun smiths were doing a roaring trade in the sale of revolvers. The police never caught on to this until all the guns in Wellington had been sold. However in Auckland all was quiet until November 8th when eight hundred farmer volunteers occupied the wharves armed with revolvers and pick handles. They also raided the offices of the Watersider's and tore down a banner from the front of the building which proclaimed "Workers of the World Unite. One Big Union".

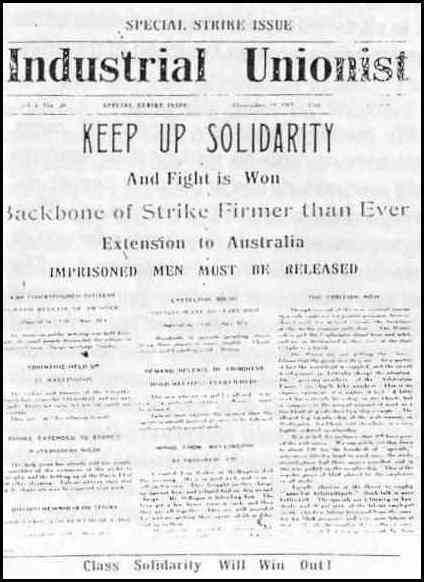

Within a few days Auckland was in the grip of a general strike. Seven thousand workers struck and thousands more were idle. Barker went back to Auckland to assist in the production of the Industrial Unionist which was coming out every second day.

'Everyone was buying the paper.' Barker continues, 'I remember being in Queen Street I had sold seven hundred copies of the paper. I was absolutely weighed down with coppers. I could hardly move and had them stacked along the side of the street.... along came a policeman who asked me to go to the police station with him.'

He ended up back in Wellington charged with sedition. The General Strike in Auckland, led by the I.W.W. forced the Federation of Labour to call a one day national strike for November 10th. It was a failure, and the next day many leading militants and wobblies were arrested. including the editor of the Maoriland Worker. Allen was appointed temporary editor. The government and employers were beginning to gain the upper hand. Nevertheless by the second week in Auckland the strike remained solid although four hundred scabs were already at work on the waterfront. After November 10th the Federation tried to extend the strike into the countryside. There was a lot of support from the rank and file of the Shearers Union, nevertheless the executive decided not to enter the struggle. Three organisers published an appeal in the Maoriland Worker, and there were several wildcat strikes, especially in the North Island. The Federation then tried unsuccessfully to involve the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants. Time was running out. The I.W.W. continued to campaign for an all out general strike, and urged the shearers to force the farmers home; if a strike wouldn't bring them back then sabotage certainly would, they believed. They also urged the strikers to form a workers militia to clear the streets of scabs and special police. Although the strike was general in Auckland, it was a different story in the rest of the country. Support in Christchurch was patchy. However Lyttelton was at a standstill. Nothing moved in Westport, and in Dunedin the entire strike committee was arrested. But the final blow didn't come from the government and employers but from the executive of the Seafearers Union when they broke ranks and came to a compromise agreement with the shipping companies. This, along with a drift back to work by some of the smaller unions forced the Auckland Strike Committee to cancel the strike on the 23rd of November. However the Watersiders, Labourers, and Drivers remained solid as did six hundred seafearers of the Auckland union. The I.W.W. bitterly criticised the strike committee for not consulting the rank and file before they acted. Meanwhile several militants had been arrested for concealing explosives, and the papers were full of stories of conspiracies. One allegedly involved a plan to blow up the Wellington express. History was to repeat itself in the 1951 Waterfront Lockout. The last issue of the "Industrial Unionist" was printed on the 29th of November. They certainly went out in an optimistic mood. Along with reports on the progress of the strike in Wellington and Christchurch they carried news of sailors refusing to do bayonet drill on the H.M.S. Psyche anchored in Auckland harbour. They once again called for a General Strike and printed an amusing report about the NZ Herald advocating sabotage; a bag of sugar in concrete to make it crumble, and some cod liver oil in the varnish to stop it drying. Along with an advert for Allen's pamphlet "Revolutionary Unionism", Bill Murdoch wrote an article condemning Trade Unionism and outlined the basic ideas of Industrial Unionism and Syndicalism.

After November the 23rd the militant unions were left isolated. The wharfies held out until just before Christmas, and the miners into the new year. With the defeat of the strike the scabs ran riot. Charlie Reeve a leading member of the I.W.W. was beaten up when he tried to board the Maheno bound for Sydney. The end of the strike also destroyed the I.W.W. as an organised group although Industrial Unionism remained a powerful force within the labour movement. It took nearly two years for the Auckland watersiders to recapture their union from the 'arbitrationists" and readmit many of the sacked strikers.

For more information see: