|

|

Bob James, Newcastle.

July, 1998.

in celebration of the Sesquicentenary of the

|

An introduction to an important, but unfortunately forgotten part of our heritage - the story of how health services spread around Australia through the 'lodge network' and enabled working people to insure themselves against sickness, death and unemployment.

|

This is Part 2 of a booklet researched by Bob James in celebration of the Sesquicentenary of the GRAND UNITED ORDER OF ODDFELLOWS. Part 1 is a brief history of the Order in Australia.

Takver, February 2000

|

From Gran Susannah,

Centenary Village,

March, 1951.

Dear Hettie and Flo,

You were asking me last time you were here why the chemist in Glebe has 'Friendly Society' on its front awning. Well, you've started me thinking about a whole lot of things and I decided to try and write them down in a long letter.

I think it's an important story and our family has been part of it for a very long time. But I'll have to go back to the beginning and ask you to use your imagination.

Can you imagine yourself a new arrival, a Johnny-Come-Lately, from Britain over one hundred years ago?

That was when your great grand father, that's my dad, EJ Moore, came ashore in Sydney Town, in June 1846. With perhaps all his worldly possessions in his wallet or in the bag in his hand, he would have stood on the wharf at the Quayside and looked around - for what, I wonder?

Probably for a friendly face, someone familiar or someone who didn't look as though they were about to murder, rob or kidnap him. And can you imagine that there, coming out of the crowd on the wharf and heading for him is a chap with a smile and an outstretched hand?

Grandfather Edward must have shaken the hand and then laughed out loud with relief, for as he told me many times later, the stranger gave him the special handshake known only to 'Brothers'. Now, he said, he knew he could relax, collect his young wife Beatrice and go with this stranger, certain that he would have support while he searched for a place to sleep, and somewhere to work.

How did my father, Edward Joseph Moore, stonemason from York in England, know these things, and how did the stranger know to greet him with a special handshake? Sounds really strange, eh?

But Father explained to me over many a cup of tea, he always had it without milk, that they knew because they were both members of 'a Lodge'. The first time I heard mention of secret signs I said, 'Hello, hello. What's going on here?'

Even harder to understand was that this was where many of our hospitals, ambulances, chemists and health funds started. But it all makes perfect sense when you put the bits together.

Anyway, by knowing that first sign, my father and this stranger both knew the other had been properly initiated and had sworn the oath that admitted him into the 'Brotherhood'.

I was always fascinated when Father told me about those early days. In the whole colony of New South Wales in the 1840's, there were only about 154,000 white-skinned people including children - certainly less than the total number of Aboriginals when the First Fleet arrived.

The cost of provisions was high and food was hard to obtain. There were no railways, no telegraph and you couldn't be sure that a letter sent from the City to the camps on the outskirts would definitely get even that far.

He told me that it was important to understand that for the first thirty or forty years after 1788, the military had dominated. When the Governor spoke, you listened, and when the military paraded and the drums beat a tatoo you kept a respectful distance. And you had to have your papers with you at all times, or risk being arrested as an escaped convict.

Public entertainment included public floggings or a pitched battle between French and Yankee sailors which would leave windows and heads broken and most of the participants sleeping it off in jail. Lodge meetings were held behind closed doors in taverns by candle-light. 'Brothers' sang songs and recited poems during the evening and it was very easy for some members to drink more than they needed.

Father said that as soon as he arrived he saw the drunkenness and fighting in Sydney, and thought lodge meetings had altogether too much of a good time about them. There was a lack of discipline which was not for him and he wanted to get the lodge away from the taverns to help Grand United make a fresh start. He had been a Methodist preacher and he burned 'to bring people to the Lord.'

Your great grandfather dreamed of finding work on an isolated property or taking one of the tiny coasters to Morpeth or, even further, to Hobart Town or Moreton Bay. He imagined himself standing tall on a stump in a clearing with the Lord's book in one hand and the Oddfellow oath in the other. He was bursting, he said, to impress the minds of his audience before they fell into bad habits. He was very frustrated with his lodge brothers and often found himself getting very angry with them.

Beatrice was already very pregnant and Edward Joseph decided one day to just get out of the City altogether and set up camp somewhere so he could start making a home. He'd heard of others doing this and thought 'the Lord' would look after his family by speaking to him more easily if he was away from the tumult and the noise.

So, he and Beatrice walked out of Sydney and 'into the scrub.' They just turned off the 'road' a bit beyond Parramatta and found a place they liked which didn't seem to have any survey posts or claim marks on it. But clearing the ground for seed and for a rough, bark shelter was very hard work. They had few tools or kitchen pots, and clean water was not always available when needed.

Beatrice got sick within weeks and this probably brought on her labour. Without a midwife to help her she died, almost taking the new-born, Aaron William, with her. The baby did survive the ordeal, and so Edward buried his poor wife and returned to Sydney, a wiser man.

On the road back, he was held up three times, the last time being rescued by a kind of local militia set up by some citizens for their own protection. He knew then that he had to return to the only people in Sydney he could trust, his lodge 'brothers'. He decided that this time he would do more listening and less 'spouting' of his own opinions.

Back in dry lodgings down near the Quay, Great-grandfather Edward looked at his infant son Aaron lying in the rough-cut cradle beside the bare wall opposite and realised he was faced with a choice. Grand United was important to him, but he just had to decide - he could either go along with some of the things that went on in Travellers' Home or he could leave and forfeit the payments he had already made and the benefits he'd already paid for.

He was behind now with his contributions but he'd been 'good on the books' for eleven years back Home. Perhaps Bea's death was 'the Lord's' way of speaking to him but in that tiny room off George Street he gradually realised the brotherhood was too important to him and that he just had to compromise if he was to ever build a better future.

He told me that he decided to work hard at learning the lodge ritual off by heart, and would try to get elected as an officer. This would mean he could be involved in enforcing the rules. He also decided he would not argue so hard against funds being spent on celebrations, say for the anniversary of the lodge's birthday, why, he might even help design a banner.

He knew the advantages of membership were worth all that a member had to give up. Others had to give up smoking and swearing, wagering and arguing about politics while they were in lodge. He only had to bide his tongue about 'the Lord' - hard, but not impossible. And he knew that many others shared his opinion that lodge had to be tightened up and made more business-like.

EJ had found to his cost that in this place help was hard to find when it was really needed and qualified doctors even rarer. Anyone suffering even a broken arm was likely to die before help came, or suffer other injuries by being jolted over rough tracks in a dray or on horseback.

He suddenly had an idea. He would argue that Travellers' Home advertise for a properly qualified doctor. He could be paid out of lodge funds to cover whatever treatments the members or their families required, especially help with childbirth.

For the first time since the loss of his lovely Bea, he began to think optimistically of the future.

But first, he had to find steady work and get re-instated in Grand United, get back to being 'good on the books.' He swung off the bed and headed out to find a 'Herald.' Jobs were often found by word-of-mouth but newspapers did carry classified advertisements.

He wasn't looking forward to it. Work in this country was from sunrise to sunset whether it was raining or fine and he'd found that it was a lot hotter than home in York. He'd have to sign a Master and Servant contract which he'd never had to before and he'd been told that it was easy for 'the Boss' to forget to pay his workers.

The Moore Family Tree:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Your great grandfather Moore had to visit taverns to find work even though he didn't drink and was part of the temperance movement which meant he opposed alcohol altogether.

But it seemed most people went 'to the pub' or met there. In the yard at the back, jugglers and dwarf wrestlers bounced and tumbled, 'doctors of medecine' sold bottles of funny smelling stuff and spruikers tried to get you into a game of pitch and toss. He himself had watched urchins and grown men there trying to catch a greasy pig, running in sacks, throwing metal quoits and winning money by having vicious dogs pursue bush rats.

Standing around waiting for work, he couldn't help getting into arguments, because everyone argued, mainly about jobs or the government. He once told me that he'd got into a real big barney with a chimney sweep who reckoned he had no chance to be anything else, and that his children couldn't expect anything else than to be chimney sweeps too. Great grandfather argued that in New South Wales, the horizons were open and opportunities a'plenty. This despite his own first experience.

The 'sweep' said even here the military ruled and to be an officer meant you lorded it over the common people, and all opportunities had to be taken with care lest someone in a high position be offended.

Another drinker butted into the talk and said the military are being withdrawn. This third man said, with a look over his shoulder, that there's just so much space, the authorities will never be able to keep the people down, we will just take the vote, and the land, and everything else.

The 'sweep' wanted to know what if people did just take, and there were no rules or order, everyone would lose because nothing constructive and long-lasting would get done, would it? And all three chaps, and a few others by then, got into talking, pretty loudly. It even came to a bit of push and shove at one stage, but nothing really bad.

Because he was a preacher EJ could read a bit and he found a note on the pub wall asking for stone masons at the Mint building, so he got work. Shortly after he met Susanah Jones and they were married in 1852. She soon gave birth to twins, Edward James and Thomas Wentworth. No twins less alike could be possible, he once said.

The young chap who became doctor to his lodge was paid 22/- by each family per year, and extra for midwifery or anything special like leeches or castor oil or for travel more than 2 miles to make a visit. He wanted the lodge to pay to shoe his horse, too, but the members refused.

In 1853, your great grand mother Susanah gave birth to a dead child, who was to be called Clara. Edward Joseph was very upset and thought about getting away again, to the gold fields this time, but he still had the twins to provide steady income for. The next son, Cain, was born in 1856 and then William the next year. From '60 to '63 four more sons were born. By then times were improving and gold had brought a lot of work for stonemasons.

Father often told me just how amazing the gold rushes were. Thousands of men simply left their paid work and walked or rode to 'the diggings'. Many more thousands came by the shipload from overseas and simply grabbed a shovel and a wheelbarrow or a pick and headed off for the latest 'rush.' Canvas tent cities suddenly appeared on the side of a hill or the bank of a stream, and could disappear just as easily.

Miners were very vulnerable to robbery and tricksters, and the troopers guarding gold shipments were few and far between. As well as sickness from living in rough bush camps, miners suffered numerous accidents as a result of the primitive way the tunnels were dug and pillared. Walking or riding at night, too, they were likely to be held up or bashed. So, many carried a gun but for insurance against the other problems they were very keen to join lodges.

It's hard to imagine but our townships grew where those camps of desperate people put their tents or stopped to rest at a fork in the road or where wagon-drivers and animals crossed a river. The government paid for the mails, the railways and roads but until there was enough income tax and a big enough public service to provide the other facilities, everything else had to be made by ordinary people - schools, churches, hotels, stores, banks, laundries and vegetable gardens.

In the Hunter Valley, one man who knew how important it was for working men to insure themselves and their families against bad luck was Joseph Wagdon. He was prepared to ride miles and miles to help men he hardly knew form lodges. A saddler by trade he worked around horses all his life and was able to pick the best.

He would finish work, say, at Morpeth, and ride to Stroud or Gloucester across creeks and along dark trails to get to a meeting where he would show ten or twenty equally dusty farm labourers or mechanics how to fill in their application forms to join. Then he would go through the ritual and explain why payments had to be kept up. And then he'd ride home again.

By the 1860's, father was getting to be quite important in the Grand United. He'd been 'through all the chairs' in his lodge, the Sons of Independence, and he was on the Sydney District Board. Young William had been killed off a horse in '64, but the next year father was elected Grand Master for the whole of New South Wales. Susanah was so proud, I can remember her saying it helped them to get over the grief.

Being Grand Master meant he had to travel a lot and he went to Braidwood for their big District celebration in '65 and up to the Hunter River District in '67. He told me about the countless sheep he'd seen from the stagecoach, and how he'd sometimes seen a lonely-looking sheep-herder all by himself with a huge flock.

Father said he would listen to men returning from Araluen or Hill End with stories of how the lodge password had helped them find a night's rest, sometimes even a few day's paid work. Wherever they had tramped they had found people talking about how hard it was to get a lodge together. Time and again, in mining camps where a large enough tent was a luxury, a group of them would meet to start something, only to find that a new 'rush' had happened and half the supposed members had disappeared. Or the lodge funds had 'walked', along with the 'trustee.'

It's strange how children, too, seem to need to rebel against their parents. Here was Edward Joseph, a non-drinker and a preacher in the Methodist Church, a high up officer in the Grand United lodge and two sons just had to go against him, the first chance they could.

Cain was barely 14 when he just disappeared. It seems he'd been getting into trouble at school a lot and one day a police constable turned up looking for him. He hadn't been to school at all. Well, Father had one letter from him years later, from San Francisco! He'd got on board a barque somehow, got into whaling and become a master mariner. And then just silence again.

One of the twins, Thomas was always a lively one too, and eventually he was killed on the Bathurst road trying to hold up a gold escort. Father tried to get hold of his body for a decent burial, though he didn't want to talk about it much, but the police had just dug a trench by the side of a track and put stones over him. Didn't even seem to think a court case was necessary. Anyway, it was too late to do anything by the time the family heard.

Father got even stricter after that, with those that were left, and perhaps he spent more time at home after he stopped being Grand Master. Anyway, I was born in 1873, a bit of a surprise!

The other twin, Edward James, eventually stood for parliament but mainly was a successful auctioneer and agent. The younger ones all got married and settled down, no trouble at all, those that survived anyway. They all joined lodges of Grand United, even me, the only surviving daughter.

Most gold miners eventually had to switch to tin, lead or coal. A mate he had at Burwood colliery, on the Hunter, told father that when they started a lodge there they decided they didn't need the passwords and the handshakes so much, or the regalia. What they wanted most was a safe place to keep their monthly contributions into the accident fund.

These miners' lodges employed doctors, too, and also elected someone to be a sick visitor as Oddfellows did. They had their own coloured collars which they still wore on Eight Hour Day and the like, and the lodge business was done pretty much the same way. A lot were in Grand United as well, but, either way, the main thing was the insurance and the sticking together. If they went on strike, it made little difference which society they were in, as long as 'brothers' supported one another.

Compared to other Orders, Grand United probably had more of what we'd call 'battling' workers. Many of them were labourers who would be put off at slack times of the year, say on a farm. So, they had to be able to move and find other work. It was not easy then to keep 'good on the books'.

There was also very little money for processions or for lodge banners and bands on special days. I remember that the brothers and sisters from different Orders got together sometimes for one big 'lodge' day. They often made their own banners and played together in one 'town' band.

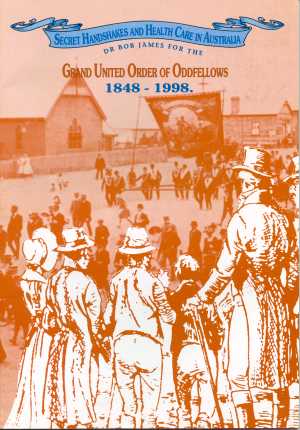

I still have a copy of the Grand United magazine from 1884 which shows that on the anniversary of the Cobar Lodge the whole town turned out:

About 11 o'clock the procession formed, the members of the Order appearing in full regalia, headed by the Cobar brass band, and after marching down the principal streets, wended their way to the ground chosen for the holding of the sports...between 400 and 500 people...At about 6 o'clock the procession was re-formed and a start made for town.

Large towns like Wagga, Armidale and Cooma were deserted and all the shops closed for the Annual Sports Gathering. The newspapers show that at Cooma in 1891 the United Friendly Societies, the Amalgamated Shearers Union and the Volunteer Fire Brigade marched together:

The old Wagga ASU banner which has done yeomen's service over the colonies and was mounted on a lorry, the new banner of the Monaro Labor Union, upon which Australia's national flower, the waratah is conspicuous and the beautiful emblems of the Friendly Societies, created a magnificent sight.

Father was off work a bit after the death of Thomas and I think it was only the payments from the lodge which got us through that bad patch. I think it was around then that Mother realised how important lodge was for all of us, not just Father.

He died the year Susanah (she always spelled her name with one 'n') and I were trying to get a ladies lodge going in Sydney in 1892. It was not a good time for anyone but the bankers. There were strikes and a lot out of work. Susanah lost interest after a while and I started my own family about then. I married a Catholic, your grand father Sean. He was an army man and in the Hibernians and none of that would have pleased my father.

We had three lovely girls who were really healthy and then I lost my darling husband in the war in South Africa. He used to say that he didn't know why he was fighting a British war but that was what an army officer had to do - follow orders.

Mother Susanah saw me through, helping me with the babes and cheering me up. Oh, I was low.

Just on the ladies' lodges. I think the only one in the whole colony that was successful was up at Wallsend. When Francis Craig, the grand old man of United up there died in '93, over 1,000 people walked in his funeral procession. More than 100 members of the Southern Cross Temple, the ladies lodge connected to Miners Home Lodge carried wreaths and marched with red sashes over white dresses. There were 250 men in Grand United regalia, too.

Mr Craig was really the father of Wallsend. Everyone consulted him and asked his advice, even about getting married and where to work and politics and the mines - just everything.

When I joined, the two issues that were stirring everyone up, graduated payments and miners health costs, were just getting to the stage of causing Miners Home, Mr Craig's pride and joy, to leave Grand United altogether. Perhaps the arguing broke his heart, I don't know. Anyway, with other lodges nearby Miners' Home established its own Order, the Australian Oddfellows' Union, in 1896. After 10 years it realised it could not survive on its own and came back in to Grand United.

For the earliest settlers the only treatments were those that they would have experienced in England. Teeth were extracted and arms were cut off or set in splints without anaesthetic. Babies were delivered and surgery was carried out with only basic antiseptics and equipment, if they were available.

When lodges began employing doctors and drawing up agreements for them to sign, anyone who was a member or in a member's family could get medical knowledge much more easily. Whatever skills or latest information the doctors brought with them was a vast improvement over what had been available. These young doctors, often just out of training, were keen to establish themselves, and so they tried hard to keep up with new developments.

Being a lodge doctor involved being paid for a certain period by each member and agreeing to be on call. This often meant very long hours and having to go along with the ingrained habits of un-educated people in remote districts. I've nursed people like that and some of them wanted to know why they weren't still being treated with leeches. I remember one old lady saying through clenched teeth, 'If they was guid enuff for my mother, they be guid enuff for me.'

The more new information, the more old habits had to die out. Lodges and doctors got together to work out ways of getting hold of stretcher beds and the springs to go under them. In many cases they had to be copied from pictures in books by a blacksmith or carpenter. Some things were invented altogether and made locally, entirely out of local materials. They were certainly repaired locally. Bandages, mattresses, sterilising equipment, everything had to be learnt about from books and either made or ordered from catalogues.

Medicines were made available in the early days rather haphazardly and many people got their pills and potions from 'quack doctors' who travelled about in covered wagons. There were 'dispensers' who were better trained and gradually chemist shops were established. Dispensers used mortars and pestles to grind up powders for medecines and early computers called 'Arithmetographs' to make calculations.

I've helped out behind the counter in a few friendly society pharmacies, and I'm glad to see you've got a job with the one in Glebe, Flo, which is where this letter started isn't it?

After my husband's death and the girls were grown, I decided to get an education. I tried to do medecine at Sydney University, women were at last being allowed in, but I had missed too much and I had to settle for nursing.

All my brothers were too old to enlist in 1914 but two of their sons were keen to go. I thought I might go to Gallipoli as a field nurse to be with them but I had got interested in the suffragettes and had attended some rallies and I was refused permission. Perhaps my Irish married name, O'Grady, stopped me too.

Anyway, I decided to do what I could to help getting supplies to the troops. Street stalls and dances and so on, and I found that my lodge 'sisters' and 'brothers' were thinking along the same lines, so Grand United floats started to appear in all the patriotic parades like the one for Belgian Day and for Jack Tar Day. Sometimes I'd dress up as Britannia or just be a nurse. There were always plenty of Chinese dragons and minstrel shows and so on as well.

As the war went on, though, membership was seriously affected and Head Office had to cover the payments of soldiers overseas and, of course, there were more and more benefits to pay out. Grand United kept going and perhaps even finished the war stronger, if anything. Perhaps in spirit, anyway, and so it was decided to build a memorial in Hyde Park where a special Grand United service could be held each Anzac Day.

Just as I was thinking our family had come out of the whole mess pretty well, and all my nephews home again safe and sound, the influenza plague struck. Three of my brothers, Samuel, James and Saul the quiet one, were all carried off within a week of each other. There were funerals and funerals and more funerals. It was the strangest time. Safe from the war and then under attack in our own back yard.

Only Edward, the eldest, Elias and I were left then. I think after that Susanah just let herself go down. She died in 1921.

You might be wondering why I haven't mentioned Aaron since he was a baby. Well, there's another mystery. He grew up really handsome and charming - could charm possums out of trees, as they say. He was very close to father but I think he felt neglected when the second family came along. Anyway, he helped father a lot in his lodge work and generally acted as his right-hand man, until just before I was born.

He started supplying medical items to lodge doctors around the State and apparently, he started getting into the travelling shows that were a bit less respectable and would disappear for weeks, and then months on end. Eventually, he just didn't come home again. One of his friends said they'd had a letter from him from America, something about fighting the Indians in Colorado. And someone else said they'd heard he was in Africa. We just don't know. Father took that very hard, too.

My dears, the changes I've seen in health care are amazing and when I think back to the tragedy of father's first wife - almost alone, without another woman to help and knowing the danger she was in, she must have suffered as much fear and terror as physical pain.

Since then, health care has changed as Australia has changed. Do go and see the displays in the museum if you get the chance.

During my working life I've had to struggle with equipment and treatments that seemed to change every year. I suppose we were learning more and more about our bodies and how they worked, so I guess it is a good thing. But it's made life difficult for secretaries of Grand United. Every year there seem to be new diseases or at least new treatments with more specialists to be somehow covered in the schedules of contributions.

And now there are so many choices! Once we were glad to know there was a bed somewhere. Now, it's different classes of patient and different levels of treatment for just about everything. And people don't seem as grateful anymore. They think they can demand their particular treatment as a right.

And just in the last twelve months the doctors and the chemists have issued what seem to be their final ultimatums, finally severing connections with the old ways.

In my time, lodges have declined in influence and Head Office has made more and more of the decisions. And health has become such a political hot potato that governments just can't afford to leave it alone. Since 1923, National Schemes have been proposed by Government for everyone, not just lodge members, supposedly making friendly societies redundant. And this time, Menzies and Earl Page seem serious.

Grand United has devised scales of payments and benefits and encouraged the general public to join, but it's also built this excellent centenary centre where the oldies go to live. I guess that's the story of friendly societies, too, growing old and creaky. Who knows?

As my life comes close to its end, I can look back on a half-century of involvement with nursing and medecine and see the gains in better health. But I miss the lodge doctors and the local control. And I miss the good times in lodge around the piano.