The 3rd of December 2004, is the 150th anniversary of the Eureka rebellion and the Eureka Stockade. The Anarchist Media Institute has initiated a campaign to reclaim the "RADICAL SPIRIT OF THE EUREKA REBELLION" which will culminate in meetings and actions at the site of the Eureka rebellion in Ballarat on the 3rd of December, 2002, 2003 and 2004. This campaign is not just a jaunt through the past. It has implications for us today. Through this campaign we will be reclaiming the spirit of Eureka: solidarity, equality and rule, by the people, for the people:- the cornerstones of the Eureka rebellion.

Our oath will be the oath taken by the diggers involved in the Eureka Rebellion.

"We swear by the Southern Cross

to stand truly by each other

and fight to defend our rights and liberties".

Eureka 2004 - 150th anniversaryThe Anarchist Media Institute is inviting everyone who is interested in reclaiming The Radical Spirit of the Eureka Rebellion, to join us on Wednesday 3rd of December at the Eureka Stockade site in Ballarat, in Victoria, to celebrate the 148th Anniversary of the Eureka Rebellion.

JOIN USFriday 3RD DECEMBER 2004

4AM to 4PM

JOIN US - Celebrate the Past by Reclaiming the Present and creating a new future. Join us at Eureka Park /Eureka Hall (cnr Stawell and Eureka Streets, Ballarat) It's time we reclaimed our history.

|

"the men from all nations, in the new world and old, all side by side like brethren here, are delving after gold" Henry Lawson.

News of the discovery of gold at Ballarat, outside Melbourne in 1851, brought a flood of gold seeking immigrants to Australia from Britain, Ireland, the United States, China, France, Italy, Germany and from every corner of the globe. Adventurers rubbed shoulders with criminals. Irish rebels, chartists and revolutionaries from the failed 1848 revolutions across Europe, came to Ballarat to find their fortunes. The Victorian colonial authorities proposed that a three pound monthly license fee be levied on diggers. After a number of protests, the fee was reduced to one pound ten shillings. This fee was still considered exorbitant by the diggers because in 1851 a squatter could buy twenty square miles of land from the Victorian government for one pound ten shillings.

The license allowed the miner to mine 144 square feet, they were expected to keep the license on them at all times and they were not allowed to mine on Sundays. The licenses were not transferable and had to be produced on demand whenever demanded to any commissioner, peace officer or other duly authorised person. The scene is set for the 1854 Eureka rebellion.

The Victorian Colonial authorities worked from the premise "that all gold belongs to the Queen" (Queen Victoria) and that the diggers making claims on crown land were a "necessary evil" that needed to be controlled with an iron fist. The first superintendent of Port Phillip (Melbourne) was La trobe. He took up is duties in 1839. In August 1849 La Trobe refused to accept convicts in the infant colony and in November 1850, the colony was separated from New South Wales and called after Queen Victoria the ruling British Monarch.

La trobe the superintendent was promoted to Lieutenant Governor and from 1851 Victoria was no longer subservient to the New South Wales Legislative Council. The Legislative Council set up in Victoria had thirty members, ten were appointed by La trobe, three were elected by Melbourne land owners. The population of Melbourne was about 80,000 by 1850. Seventeen were elected by a small band of rural land holders. La Trobe also had the power to appoint a four member Executive Council to exercise his authority. All these structures were subservient to the British Colonial office. By 1851, the Aboriginal population of Victoria had through dispossession, a policy of turning a blind eye to the pastoralists massacres and disease that reduced the population to such a degree that they were expected like in Tasmania to disappear in two or three generations.

Although gold had initially been discovered at Golden Point in Victoria in 1838, it wasn't till 1849 that a shepherd called Chapman discovered significant gold about 100 miles from Melbourne. His initial find was followed on the 29th of June 1851 by a significant find, James Hargraves a man who had learnt his trade on the Californian gold fields. In August 1851 John Regan and John Dunlop discovered gold at Ballarat. Gold production of this stage was alluvial (diggers scratched and wished the surface dirt to find about half an ounce of gold a day). All this changed in mid September 1851 when the Cavanagh brothers, miners with the Californian experience below their belts, extracted 60 ounces of gold in two days at Golden Point (the first site that gold was discovered at in 1838, a site that had been thought to have been mined out long ago) by digging thirty feet into the ground. Within days of the news reaching Geelong and Melbourne six thousand diggers pored into the Ballarat, Clunes goldfields.

In steps, the LieutenantGovernor La trobe, in order to derive revenue from the gold discoveries, maintain colonial authority on the new goldfields and stop the colonial labour force from flocking to the goldfields. La trobe imposed a mining license of thirty shillings a month on diggers to mine 64 square foot of dirt. Licenses were only to be issued to men who "had been properly discharged from employment or were not otherwise improperly absent from hired services".

The mining license was imposed more as a method of maintaining control over the diggers than as a revenue raiser. The scene was set for the most important rebellion seen in Australia's history.

La trobe's (the Lieutenant Governor of the newly established colony of Victoria) plans were very simple, he hoped that by raising revenue through the miner's licenses he could establish an enforcement system to keep the miners in their place and maintain the status quo. The first gold commissioner appointed by La trobe was F. C. Doveton a petty despot if ever there was one. Although Doveton had been told by the colonial secretary, William Lonsdale "to be discrete in demanding the fee" because of resistance to its introduction in Melbourne, Doveton decided that the only way to maintain order was by the establishment of a take no prisoners mentality. He appointed his friend David Armstrong a policeman and crown bailiff as gold commissioner and magistrate. The ranks of the newly established police force on the gold field's were swelled by contingents of native police and their white officers from New South Wales. Within a few months, enough native and non-native police, as well as magistrates, were in place to enforce regulations regarding mining licences.

La Trobe visited the gold fields in October 1851. He was upset that Doveton was not able "to extract a miners license from every miner" and moved him to Mount Alexander, appointing William Mair as the new gold commissioner. He was told that the license fee must be collected from every digger and that the letter of the law must be upheld. He was so impressed by the wealth being extracted on the gold field's, that he recommended that the gold fee be increased from 30 shillings to three pounds per month. The simmering protest movement against the fee and the way it was being collected gathered a head of steam. In order to nip the protest movement in the bud, he gave Mair the authority to appoint as many licensed constables as he wanted. After resistance from his Executive Council, La trobe was forced to back down on his proposal to increase the license fee to 30 shillings. La trobe, a man who's memory is still honoured in Melbourne town today, set in train a series of events that would lead the diggers to take up arms to "protect their rights and liberties". Instead of placing an export duty on gold, a tax that would only effect those who found gold, La trobe decided that in order to maintain total social control on the god field's, he needed to tax every digger who wanted a claim.

La trobe appointed W.A. Urquhart to survey Ballarat, the firstgold field's town. Urquhart's plan was very simple, he chose high ground that leveled off from the river and drew six streets, and the main street was to be three chains wide and the other streets, which bisected the main street, were to be two chains wide.

Urquhart named the main street Sturt after his brother, a Melbourne policeman. His love of the forces of law and order lead him to name the main streets after those who had come to enforce Queen Victoria's laws. Streets were named after Doveton the first Gold Commissioner, Dona the first police commissioner and Lydiard his assistant. A street was also named in honour of the police thug, Armstrong, the police commissioner that did so much to enrage the diggers. A man who used brute force and lined his own pockets was honoured by Urquhart with a street name.

Urquhart also used Kulin names (the local indigenous inhabitants) to name the swamp, Wendouree and the river that ran through Ballarat, Yarrowee. He completed his plans within a month and returned to Melbourne.

Interestingly the names of those, who through their callous actions caused the Eureka Rebellion, are still honoured, while those who fought and died are forgotten. As part of the 150th celebrations some of Ballarat's street names should be changed to reflect the radical nature of the Eureka Rebellion. This could be one of the aims of those of us who want to reclaim the radical spirit of the Eureka Rebellion.

From the beginning of European colonisation in Victoria, in 1836 to 1851, the landed aristocracy had taken over most of the land in Victoria and cleared the indigenous inhabitants off their land in the most brutal and barbaric fashion.

The squatters had only paid the Victorian government around a quarter of a million pounds for the privilege of owning most of Victoria. Most had not bothered to pay more than a token deposit for some of the best land in Australia.

The discovery of gold in such vast quantities, the resultant inflationary pressures and the flooding of the goldfields with the "trash of all nations" posed a direct threat to their economic and political hegemony. La trobe the Victorian Lieutenant Governor's decision to impose a monthly license fee on each digger was the way the government believed it could exert its control over the miners and maintain the status quo. The police forces sole objective on the goldfields was the collections of the license fee; no attempt was made to control crime except "sly grogging". The police augmented their meagre wages by legally pocketing part of the license fees they collected and any fines they were able to impose.

As more and more diggers flocked; to the gold fields the old maxims that prosperity depended on, "hard work and frugality, honoring the Queen and her representatives and respecting law and authority" were threatened by the spectre of people making a fortune in the matter of hours, not years. To make matters worse, many of the diggers had no respect for authority, let alone a constitutional monarchy. Many of these men were veterans of the 1848 European revolutions that convulsed Europe and shook the established order. La trobe the governor faced this threat with a rapidly shrinking police force that regularly threw away their gold braided uniforms and joined the throngs digging for gold. In December 1851, he had a military force of 44 men. This was increased by a further 30 in January 1852. The military presence had been kept low in Victoria to allow the squatters to get on with the task of re-directing the original inhabitants. Law in the frontier lands was administered by the squatters with poison and the gun. It was common knowledge that the Colonial office in London was concerned about the wholesale massacre of the colonies first inhabitants. It would have impeded the squatter's attempts to clear the land of "human vermin" so their sheep and cattle could graze on it, if too many of her majesty's soldiers were around.

As the number of diggers increased La trobe had difficulty in maintaining the status quo. In October 1852 his problem was temporarily overcome when the Vulcan arrived with five companies of the 40th regiment. By January 1853, they were stationed in Ballarat and were incorporated in a mounted troop that for all intentional purposes acted as a military force on the goldfields.

La trobe sailed back to England on the Golden Age on the 6th May 1854. He had overseen the growth of the colony from a population of around 5000 in 1839 to over 250,000 in 1854. Most of the growth had occurred in the last three years of his rule as Lieutenant Governor. The acting Governor John Fitzgerald Leslie, held the spot warm for the New Governor Charles Hotham till the 26th of June 1854.

On his arrival Hotham was lulled into a false sense of security by the presence the 60,000 people who welcomed him, as he rode over the Yarra under a triumphal arch, with the catchy slogan (even then spin doctors were in full hue and cry) "Victorian welcomes Victoria's Choice" those souls that ruled the empire over which the sun never set understood that if they needed somebody who could rule Victoria with an iron fist. The folk in the foreign office understood that rebellion was in the air in Victoria and that the iron fist would have to be taken our of the velvet glove if Victoria was to remain part of the British EMPIRE.

Sir Charles Hotham was a self-made man who had put down an Argentinean insurgency in 1845 and commanded the British naval forces on the West Coast of Africa in 1846. He kept discipline aboard his ships in a brutal manner. He understood that force would need to be used if the miners organised themselves. In order to help Hotham maintain order, the Colonial office sent to Victoria five companies of fifty men before Hotham arrived. Hotham also had the authority to call for reinforcements from Van Diemens Land (Tasmania) or New South Wales if required.

The Colonial officer's mind on the possibility of revolt had been sharpened by the chartist upheaval in England in 1848. The European revolution of 1848, the American war of Independence and periodic Irish rebellions. Hotham caught up in the celebratory mood at his arrival, let his guard down and while in Geelong proclaimed "all power proceeds from the people" while he expressed those sentiments he toured the goldfields gaining a feel for the situation, using his military mind to assess the situation. Hotham came to the conclusion that his soldiers would have a hard time of putting down a revolt if the miners stayed in their mine shafts and picked off the Queen's soldiers as they tried to put down a revolt. He left the goldfields with the knowledge that he could easily put an end to a rebellion if the diggers gathered together to face his troops. Hotham returned back to government house in Toorak and quickly calculated that only about half the diggers here pay license fees. Faced with a financial crisis, brought on by the cost of increasing number of police and soldiers in the colony and growing levels of unemployment in Melbourne, he understood that he needed to increase State revenue. In order to fill the colonial cotters, he ordered that license search's be carried out on all the goldfields at least twice a week. La trobe had kept the lid on the possibility of rebellion by only endorsing one license hunt a month. The tacit agreement between diggers and government, that had kept the pot from boiling over, had been broken by Hotham's order.

Those who represented the government on the Ballarat goldfields lived in "the camp". The camp was situated across the road from the diggings. It provided a home and an office for police, soldiers and government officials. Its presence acted as a physical reminder to the diggers of the source of their oppression. Corruption was the fuel which kept the wheels of the camp an oasis of splendor in a sea of squalor turning.

The Editor of the Ballarat Star Samuel Irwin and the Diggers Advocate George Black described the camp in their newspapers as "a kind of legal store where justice was bought and sold, bribery being the governing element of success and perjury the base instrument of baser minds to victimise honest and honorable men, thus defeating the ends of justice". The officials in the camp were rapidly able to make their fortunes by using their positions to augment their incomes. Their links with local businesses, their toleration of the sly grog trade, their ability to issue business licenses to only those who were willing to pay bribes and their ability to manipulate the license system to line their own pockets combined to make the camp, in the diggers eyes, the source of all their problems.

This sad state of affairs was compounded by the diggers monthly trek to the camp to have their licenses re-issued. This ritual trip to the camp built up the hostility and resentment that spilt over into the Eureka rebellion. The camp embodied all that was wrong in the goldfields. The ill feeling between the diggers and the camp was escalated with the murder on the 7th of October 1854, of a well liked digger on the Ballarat goldfields, James Scobie. James had been felled with a blow to the back of his head with a shovel in the early hours of the morning of the 7th of October. Suspicion immediately fell on the proprietor of the Eureka Hotel, Ballarat's largest hotel, James Bentley. A ticket of leave man from Van Diemens Land who had gone into partnership with officials from the Camp and built the Eureka Hotel at the cost of a small fortune in 1854 thirty thousand pounds.

On the 12th October 1854, James Bentley was brought before a judicial inquiry that consisted of three camp officials Rede, Johnston and O'Ewes. Bentley was acquitted of any charge although it was common knowledge on the Ballarat goldfields that O'Ewes was Bentley's secret business partner. The murder of Scobie and the acquittal of the main suspect by corrupt government officials sent the temperature rising on the Ballarat goldfields.

A meeting was called for 6.00am Tuesday the 17th October at the spot where Scobie was killed, to pressure the colonial authorities to charge Bentley, the owner of the Eureka Hotel with his murder. By midday over 10,000 diggers (half the population of Ballarat) had gathered at the spot. A resolution was put to the crowd by Hugh Meikle the chair and seconded by Russell Thompson. Both men had acted as jurors in the coroners inquest. That failed to charge Bentley with Scobie's murder.

"This meeting not being satisfied with the manner in which the proceedings connected with death of the late James Scobie, have been conducted either by the magistrate, or by the corner, pledges itself to use every lawful means to have the case brought before other and more competent authorities". Around thirty police armed only with staves were sent to protect the hotel. Bentley fearing for his life jumped on a horse and rode to the police camp about three minutes away from the Eureka hotel. The crowd enraged by his escape, started to stone the hotel. The 40th regiment, under Lieutenant Broodhurst came to offer the police assistance and lined up on the right side of the Eureka hotel. As the diggers continued to pelt the hotel with stones, a fire broke out in the canvas bowling alley next to the hotel. The fire soon spread to the hotel.

The 40th regiment refused to join the police in their attempts to put out the fire and rode off leaving the Eureka Hotel to burn to the ground. The diggers, by their actions had made a mockery of the police, soldiers and those in authority. Robert Rede the chief commissioner on the goldfields had been pelted with eggs and garbage when he ordered the crowd to disperse just before the hotel burnt down. Two diggers who had been arrested by the police for lighting the fires were rescued from the police. At this point the police followed the military, tails between their legs and returned back to the camp.

That night a thousand rounds of ball cartridges were issued to the police and military, in case the diggers tried to storm the camp and lynch Bentley. In order to buy time and increase the police and military presence in Ballarat, Robert Rede the chief commissioner had Bentley charged with murder but promptly released him on 200 pounds bill and 100 pounds surety.

The democratic nature of the miners' movement was reinforced by the calling of regular mass meetings. Although going to a meeting meant the loss of valuable digging time, the Ballarat miners were so incensed at the selective arrest of McIntyre and Fletcher for the burning of the Eureka Hotel, that a mass meeting was called for Monday the 23rd of October, to protest against their arrest.

Bakery Hill, 500 metres from the military camp and a 1000 metres from the smoking ruins of Bentley's Eureka Hotel, became the focal point for a mass meeting of 10,000 diggers and their supporters. Considering that the total population of Ballarat was only 25,000, it was evident how important the diggers felt about the injustice that was meted out to the arrested men. As the afternoon wore on, it was decided to form a Digger's Right Society, to maintain their rights. At this early stage, there was no hint that the miners wanted to overthrow British authority. The leadership of the movement was British to their bootstraps. Neither the Irish, German or American contingents of the Ballarat goldfields were actively involved in the movement.

A series of public meetings held in November kept the issue bubbling along. On November the 1st, 3000 diggers met once again at Bakery Hill. They were addressed by Kennedy, Holyoake, Black and Ross. The diggers were further incensed by the arrest of another seven of their numbers, for the burning down of Bentley's Eureka Hotel. Further military reinforcements had allowed the leader of the camp, Rede, to make further arrests.

The meeting resolved "that the diggers of Ballarat do not enter into communications with the men of the other goldfields, with a view to the immediate formation of a general league, having for its object the attainment of the moral and social rights of the diggers." Interestingly, two weeks before the 1st of November meeting, the Bendigo diggers had proclaimed that they would "never cease agitating until they all possessed all the rights, political and social, of British subjects".

Rede the chief gold commissioner on the Ballarat goldfields, and Governor Hotham were concerned that what at first seemed to be a non-disciplined rabble, was becoming a social and political movement with specific aims and objectives, that could be hostile to the British monarchy.

As Governor Hotham came under increasing pressure, he turned to the squatters for support. The squatters, although a tiny minority of the Victorian population, held the majority in the Legislative Council. They had built their wealth on the blood and bones of Victoria's indigenous inhabitants, increasing the size of their runs by the use of guns and poison, treating the indigenous inhabitants as little more than vermin. Ten years previously in 1844, the squatters had been involved in their own struggle with the crown, threatening to take up arms against Governor George Gibbs if he attempted to pass a number of proposed land regulations that asserted the authority of the Crown over the squatters.

Working with their mates in a colonial office in London, the squatters engineered the recall of Governor Gibbs in 1847 and continued to grab as much land as they could. In 1854 they fell in behind Governor Hotham, offering him their full support because they understood that the miners were the biggest threat to their power and wealth. In less than 20 years, Victoria's indigenous inhabitants had been reduced to such small numbers by disease and warfare that they no longer posed any serious threat to the squatter' plans for expansions. In 1854 the Crown guaranteed security of tenure of the land to the squatters. The squatters knew that if the crown lost the struggle against the diggers all the land they had amassed would have been redistributed to a population that was hungry for access to land. The emerging business class that had prospered as a result of the gold rushers also threw their weight behind the Governor. The security which the Crown provided, allowed them to expand their business interests and charge outrageous prices to the diggers. Hotham's actions were fully supported by The Argus, the forerunner of Melbourne's Herald Sun and The Sydney Morning Herald. His position was not supported by the newly formed Age in Melbourne and the local newspaper The Geelong Advertiser, The Ballarat Times and the diggers own paper, The Diggers Advocate. As the local papers relied on local advertisements and local readers for their survival, they tended to reflect the interests of the diggers while The Argus, which depended on the squatters and Melbourne business support for their survival, threw their weight behind Hotham.

As October 1854 ticked over into November 1854, Hotham secured the uncritical support of the squatters, business, the London Foreign office, the Legislative Council and Melbourne's major newspapers for armed intervention in Ballarat. Over the next 5 weeks the scene was set for what eventually happened.

On Saturday the 11th of November, ten thousand miners meet at Bakery Hill and formed Ballarat Reform League. The meeting began in a tent but as thousands arrived it was moved onto Bakery Hill. The diggers set both short term and long term political goals for the Ballarat Reform League. The League used the British Chartist movement's principles to set their goals. The meeting passed a resolution "that it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called on to obey that taxation without representation is tyranny".

Many of the miners at the meeting had been involved in British working class uprisings in the 1840's. They were familiar with Chartist demands for universal manhood suffrage, abolition of the property qualifications for members of parliament, payment of members and short-term parliaments. Many were aware of the brutal way British troops put down working class movements in Newport and Birmingham in the late 1840's and many of the foreigners at the meeting had been involved in the failed 1848 revolutions across Europe. The Bakery Hill meeting decided to secede from Britain if the situation did not improve. "If Queen Victoria continues to act upon the ill advice of dishonest ministers and insists upon indirectly dictating obnoxious laws for the Colony, under the assumed authority of the Royal Prerogative, the Reform League will endeavour to supercede such Royal Prerogative by asserting that of the People which is the most Royal of all Prerogatives, as the people are the only legitimate source of all political power."

As well as these long term goals, the diggers wanted the Gold Commissioners on the goldfields, disbanded and they wanted both miners and storekeepers licenses abolished.

The meeting agreed to set up a large permanent tent at Bakery Hill, to act as an office for the Ballarat Reform League. The League decided to issue membership cards to members. John Basson Humffrey was elected President and George Black, Secretary of the League. The meeting also passed the motion "the meeting hereby pledge themselves to support the Committee in carrying out its principles and attaining its objects which are the full political rights of the people".

The scene was now set for an escalation of the conflict between the Ballarat miners and the Colonial authorities. One side would be forced to submit to the authority of the other.

After a number of mass meetings and the burning down of the Eureka Hotel, James Bentley the republican who was initially cleared of any involvement in the death of the miner James Scobie, appeared in the Victorian Supreme Court to face a charge of murder. Catherine Bentley (his wife), John Farrel the former Castlemaine Police Magistrate and a barman at the Eureka Hotel, William Hance, were also charged with the same murder. Catherine Bentley was acquitted but James Bentley, Farrel and Hance were found guilty of manslaughter and were sentenced to three years hard labour, a relatively light sentence for the times.

Of the ten people who were randomly arrested from the 10,000 miners who were at the Eureka Hotel rally when it burned down, three were committed to stand trial for the fire. Andrew McIntyre, Thomas Fletcher and Henry Westerby were charged with rioting and burning down the Eureka Hotel. After a spirited defence by their lawyer Richard Ireland, the jury retired and returned five hours later with a guilty verdict, but made a strong recommendation for mercy. The jury stated that the defendants would not have found themselves in court on these charges, if the authorities had done their duty and charged Bentley with murder in the first place. The judge gave the defendants prison sentences, ranging from three to six months. The arbitrary nature of the arrests and the prison sentences, further infuriated the Ballarat miners, confirming their suspicions that the courts always acted in favour of those with power and wealth (seems little has changed nearly a hundred and fifty years later).

Governor Hotham's role in the court cases was questioned by the miners. It was felt that Hotham's words were not matched by his deeds and he was acting "like a martinet". The people were crying out for land, representation and justice, and all they continued to receive was increasingly costly miner's licences and more frequent licence hunts. Faced with an almost empty treasury and a potentially hostile population, Hotham fanned, not extinguished the flames of discontent. He retrenched over a 1000 public servants and asked the Gold Commissioners to increase the licence hunts and collect every penny owed to the State. As the tensions rose, rumours abounded and Governor Hotham realised that he was faced with a potentially insurrectionary situation and needed to send more troops to maintain order and collect licence fees on the goldfields.

On the 25th and 26th of November, a delegation selected by the executive of the Ballarat Reform League, arrived in Melbourne to prepare for a meeting with the Governor. On Sunday the 26th of November, John Humffrey a former Welsh Chartist, George Black the editor of the Digger's Advocate and Thomas Kennedy a former Charist and Baptist preacher meet Ebenczer Syme the editor of the Argus, to discuss how they would present the Ballarat Reform League's position to Governor Hotham on Monday morning.

Hotham, his Attorney General Stawell and his Colonial Secretary Foster, meet the delegation at Government House in Toorak. Hotham had a shorthand writer present at the meeting to record the conversation.

The delegate's mandate included the resolutions that were passed at the mass meeting in November, which covered universal suttrage as well as abolition of he miners and storekeepers licenses. They also had a mandate to ask for the release of Fletcher, McIntyre and Yorkey, the three diggers who were arbitrarily arrested and imprisoned for the fire at Bentley's hotel. George Black opened the meeting by demanding that the Governor pardon the men. Hotham, a naval man who set great store on rank, was flabbergasted that the delegation made demands of him and the government. Although the digger's delegates asked the Governor to make some concessions, the only concession he was willing to make was to have one digger's representative elected to the Legislative Council. The delegates refused to accept this paltry gesture and went back to the Ballarat Reform League with nothing to show for their efforts.

The meeting on the 27th of November was the last chance Hotham had to avoid bloodshed. He chose to ignore the diggers' demands and continued to send more troops to the Ballarat goldfields. Within six days of this meeting, the rebellion had been put down by Hotham in a sea of blood.

Hotham the Victorian Governor, understood that he had a problem on his hands. The burning of Bentley's hotel and the transformation of the struggle about mining licences into a struggle for human rights, raised some very serious concerns at Government House. In an effort to bolster support for his impending military action, Hotham strengthened his alliances with the squatters.

Once he had cemented his alliance with the squatters, he turned his attention to bolstering the military presence in Ballarat, as Hotham understood that his ultimate authority lay in his ability to thwart any uprising. Hotham ordered 435 military personnel and police to augment his Ballarat forces. The commander of the military in Victoria, Major General Sir Robert Nickle, was asked to put Captain Thomas of the 40th Regiment in charge. By the end of November 1854, the 12th and 40th Regiments were camped at Ballarat, they were accompanied by foot mounted police as well as naval personnel. Hotham was concerned that the revolt may spread to Melbourne, so he organised naval reinforcements to assist the military and the police. Two officers and seventeen seamen from the HMS Fantome, with the ship's six pounderfield piece as well as two officers, seventeen seamen and six pounderfield pieces were sent from the HMS Electra to Ballarat. Thirty seven marines from these ships and two field pieces were supplied to guard the Treasury building in Spring Street, Melbourne. As well as this, the Ballarat forces also had access to two twelve pound Howitzers they could use if called upon. The military carried 1842 muskets and bayonets that could fire two shots a minute. Hotham knew that if the miners decided to establish and protect a camp, he would have the necessary firepower to overcome whatever his troops faced. The miners had muskets in various states of disrepair. When they decided to set up the Eureka Stockade, a blacksmith's shop that was inside the Stockade was used to manufacture pikes for the miners that did not have access to muskets.

As more and more police and military were sent to Ballarat, several hundred special constables had to be sworn in, to keep order in Melbourne. As the end of November arrived, the scene was set for the confrontation with the miners that Hotham had engineered to occur.

On Thursday morning the 30th of November 1854, the day after the mass meeting at Bakery Hill, the military and police raided he miners on the pretext of looking for licenses. Outraged by the arrest of eight miners at bayonet and rifle point, the diggers spontaneously gathered at Bakery Hill. As Bakery Hill was exposed to attack, the miners agreed to march to Eureka, a site that they felt was less exposed.

Captain Ross, a Canadian, unfurled the Southern Cross and marched at the head of the rag try column. About 1000 miners, many armed with only picks and shovels arrived at Eureka. Once they arrived, the 13 leaders that had been elected the previous day at Bakery Hill met to discuss tactics. They constituted themselves into "a council of war" for the defence of the miners from military and police attack.

Peter Lalor was chosen as "commander in chief". He was given a mandate to "resist force by force". After his election as commander in chief, the diggers began to erect a simple fortification about 200 metres from the remains of Bentley's hotel. They enclosed about an acre of relatively flat ground that had some miners' huts and stores on it, but no shafts. They encircled it with slabs of timber and shoveled some earthworks round the slabs to strengthen them. Once the stockade had been completed, about half the men who had marched to Eureka, marched back to Bakery Hill. As the sun was setting, Captain Ross sword in hand hoisted the Southern Cross. Lalor, rifle in hand jumped on a stump and asked those present to swear on oath to the new flag. Lalor took off his hat, knelt and swore the oath on behalf of the assembled miners. "We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties".

As dusk fell, they took down the Southern Cross and marched back to Eureka. Once they arrived back, Lalor called a meeting of the elected captains who decided to send one last deputation to the Gold Commissioner Rede, telling him they would lay down their arms and return to work if the arrested diggers were released and no more licence hunts carried out. A three man deputation was told in no uncertain terms by Rede that it was his job to maintain the Queens authority, not negotiate with men who were using the licence as "a mere clack to cover a democratic revolution".

The Eureka movement was first and foremost an open democratic movement. Those who were elected to leadership positions took their mandate from mass meetings. As the movement was open and democratic, its ranks were able to be infiltrated by agent provocateurs and police and military spies. The High Treason trials that occurred after the rebellion was crushed, flushed out many of the provocateurs and secret agents as their evidence was required to conduct the trials.

Henry Goodenough a policeman turned out to be the most important spy and agent provocateur in the colonial authority's armory. Goodenough both on agent provocateur and policy spy went about the newly created stockade on the afternoon of Thursday the 30th of November 1854 urging the miners who were drilling to attack the government camp. He slipped out of the stockade that evening and told Rede the Chief Commissioner on the Goldfields that the miners would attack the government camp at 3 o'clock Friday morning. Goodenough was a man who was so filled with his own self-importance that he had no hesitation in twisting the truth to bolster his own reputation with his superiors.

Goodenough had befriended Raffaelo Carboni one of the leaders of the Eureka rebellion and once the rebellion ended in a sea of blood, he had no hesitation in arresting Carboni at pistol point, although Carboni was attending to the wounds of a digger who had been shot six times when he was arrested. As the colonial authority's prize witness, he was used extensively by the government as a prosecution witness.

Goodenough was trotted out of the trial of John Joseph a black American who was charged with High Treason. As Joseph was the first one tried it was important the prosecution got their evidence right. Goodenough swore that Joseph was in the stockade at the time of the attack. He was also used in the trail of Timothy Hayes another one of the 13 miners that was charged with High Treason. He swore that on the 30th November at Bakery Hill, Hayes had urged the miners "to fight for their rights and liberties". His testimony came unstuck when he admitted under questioning, that he had also urged the miners "to fight for their rights and liberties". His evidence of the Carboni trial was also discredited.

I have not been able to find out what happened to trooper Henry Goodenough, although I note a H. Goodenough from Victoria is included in the list of the 800 descendants of the Eureka rebellion. If anybody has any information on this "good citizen" or has the time to delve into it, call me on 03 9828 2856 or write to me at PO Box 20 PARKVILLE 3052 MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA or email me at anarchistage@yahoo.com.

Few diggers slept in the stockade on Friday night, they slept in their own tents or in friend's tents and returned to the stockade on Saturday morning. Drilling recommenced at 8.00 in the morning and the blacksmith inside the stockade continued to make pikes for the diggers who didn't have access to firearms. Drilling stopped around midday when the catholic priest Father Smyth arrived to tend to the needs of the Irish Catholics. They listened to his pleas no to fight, but sent him on his way empty handed.

By mid afternoon 1500 men were drilling in and around the stockade. Around 4 o'clock that afternoon two hundred Americans, the Independent Californian Ranges under the leadership of James McGill arrived to lend a hand. Their arrival bolstered the men's spirits as the Independent Californian Rangers were armed with revolvers and Mexican knives. McGill who had had some training at West Point was appointed second in command to Lalor.

McGills put his military training to work and set up a sentry system to warn the stockaders of the British attack. He also decided to take most of the Californian Rangers out of the stockade that night to intercept British reinforcements from Melbourne. By midnight only about 120 diggers remained in the stockade, most were armed with a few rounds about twenty had only crudely fashioned pikes. Rede, the Chief Gold Commissioner's network of spies relayed the information that most of the men who had spent the day drilling had gone back to their tents for the night and that the Californian Rangers had left the stockade on a wild goose chase.

Rede understood that the time to crush all "that democratic nonsense" that the miners had spoken about and agitated for over the past three years had come. He knew that if he didn't use the 700 to 800 men he had at his disposal at the government camp, he would lose the opportunity to nip the revolt in the bud. Late on Saturday night he chaired a meeting with Captain Thomas the commander of the 40th regiment, Captain Pasely of the Royal Engineers and Commissioner Amos that organised the attack that was launched on the stockade a few hours later.

Rede the Chief Commissioner on the Ballarat goldfields and Governor Hotham were preparing for war. On Tuesday the 28th of November, a party of two officers and eight men from the 12th regiment were attacked as they guided wagons full of ammunition through the Eureka diggings. A violent confrontation occurred, the wagons were overturned and the 12th regiment's drummer boy was injured.

By evening Rede had a considerable number of military and police reinforcements in the government camp. Eight officers and 248 men from the 12th and 40th regiment that arrived that day bolstered the number of military and police under arms in the camp to 435 officers and men. Soldiers and mounted police had poured in from around the state. Thirty-nine mounted troopers arrived from Geelong. Of the 256 men that arrived that day, 106 men from the 40th regiment under Captain Wise, were sent from Geelong. Reinforcements were also sent from Castlemaime, as well as directly from Melbourne.

At around 2.30am on the morning of Sunday the 3rd of December, Rede mobilised 296 police and soldiers to attack the Eureka stockade. 182 mounted and foot soldiers from the 40th and 12th regiments led by Captain J.W.Thomas were accompanied by 94 police mounted and on foot. The police were under the command of Sub Inspector Taylor. Around 200 soldiers and police were left in the camp under the command of Captain Atkinson in case reinforcements were needed during the battle.

The total of men under arms that made their way to the stockade was 296. More than double the number of miners left in the stockade. The soldiers and police were armed with 1842 muskets and carried around 60 rounds of ammunition. The average rate of fire of the muskets was two rounds per minute, bayonets were secured to the muskets by a spring catch. The 17 officers who led the men into battle were armed with regulation pattern 1845 swords, officers did not carry firearms in the Eureka battle. The 40th regiment was selected for service at Eureka because it had a mounted infantry division of 50 privates, 2 sergeants, 2 corporals and 1 bugler. It was formed in December 1852 to act as an elite mobile military force that could be sent to trouble spots around the state at short notice. The weapons at the disposable of the military and police, made the rifles and crudely manufactured pikes that the miners had, look like wooden toys.

The government camp was about 3 kilometres from the Eureka stockade. At 2am on Sunday the 3rd of December 1854, the troops fell into their ranks between the government camp and soldiers hill. They remained there in complete silence till 3.10am when they began silently marching in a south-easterly direction, hiding behind Black Hill before striking out towards the camp. They halted near the aptly named Free Trade Hotel about 200 metres from the stockade.

The stockade had been erected at the southern end of the Eureka diggings, it consisted of chopped down trees, sand, branches, slabs which were used to line the miners shafts as well as overturned carts. The stockade was nearly 2 metres in height in some places. The soldiers and police advanced from behind the hotel and moved towards the stockade that enclosed around an acre of land. By this time dawn was breaking, Captain Thomas and Police Magistrate Hackett rode towards the stockade on their horses. When they were around 150 metres from the stockade, all hell broke loose. The government claimed the first shot was fired by the miners, the miners claimed that they only opened fired after the government forces opened fire on them. Interestingly, Hackett the Police Magistrate, never read the riot act giving credence to the miners' view that Rede the Chief Gold Commissioner on the goldfields, had taken the opportunity to launch a sneak attack and crush the miners militarily.

At around 4.45am Harry de Longville, a sentry at the stockade, noticed the troops and police and fired a signal shot to rouse the 120 diggers left in the stockade. At this point Captain Thomas gave the order to commence firing and the police and military moved forward rapidly in an attempt to maximise the confusion among the miners caused by the surprise attack. A group of 40 assault troops from the 40th regiment, under the command of Captain Wise, attacked the stockade from the back (north side). About 30 mounted troops from the 40th (Hotham's elite shock troops) approached from the north-east. 24 police took up positions to the right of the Wise party and 112 foot soldiers from the 12th and 40th regiments approached from the west. 70 mounted police rode in from the south-west. The stockade was now completely surrounded. The police, foot soldiers, mounted police and soldiers kept firing as they advanced. Within a few minutes of the initial attack, the stockade was breached at the north and west flank.

Peter Lalor the leader of the diggers, attempted to bring order to the confusion surrounding him. He soon realised that the stockades had no options but to fight. If they attempted to surrender they would have been cut down by the withering fire that was directed at them. Realising that he had a very small force under his command with limited firepower, he jumped up on a miner's mound and ordered the diggers to stop firing and save their ammunition till the soldiers and police were within range. He ordered the pikemen forward, but as he was exposed, it only took a few minutes before he was shot in the shoulder and ordered his men to save themselves as he was hidden under some wood.

The first volley fired by the diggers as the soldiers and police breached the stockade at the north and west end of the stockade, slowed the soldiers advance. By this time about 30 pikemen using primitive pikes that had been made in the forge in the stockade, used their simple weapons to slow down the government advance. The pikemen, under the leadership of Patrick Curtain, were unsung heroes of the stockade, using their flimsy pikes against muskets slowing the advance enough to allow many of the diggers to flee the stockade. Of 30 pikemen who took part in this life and death struggle, only 5 or 6 survived to tell the tale of December 3rd 1854.

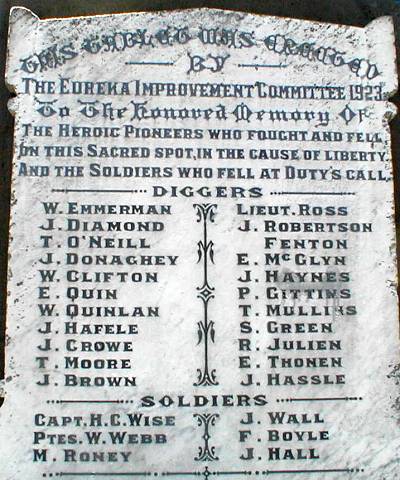

About 20 or 30 Californian Rangers armed with revolvers under the leadership of Charles Ferguson, had left the stockade at around 1.00am to look for a cache of arms. Fearing that they had been lured out of the stockade, Ferguson returned with the Californian Rangers just before the stockade was invaded by the government forces. By now many of the diggers lay wounded in the stockade. Those who tried to escape were ran down by the cavalry that had now surrounded the stockade. Within 15 to 20 minutes of the first shot been fired, the back of the revolt had been broken, the troops and police were in complete control of the stockade, suffering few injuries. Three privates lay dead or dying, Michael Rooney, Joseph Wall and William Webb, 12 more were wounded, Captain Wise was also wounded, shot in the right thigh and upper part of the fibula tibia. Although surprised by the attack, the diggers had fought a hard battle. The foot soldiers took the most casualties among the government forces as the cavalry and the foot and mounted police had not been involved in the battle proper.

Although the battle was over in 15 minutes, the killing went on till the stockade was bathed in sunlight. It's only in the last decade that Eureka has been described as a massacre. Although the evidence of the atrocities committed by the police and to a lesser extent the soldiers has been lying in official records for almost 140 years, very few researchers have been interested in this important part of the Eureka story.

The massacre at Eureka is the pivotal point of the Eureka story. The massacre turned a tiny insurrection in a corner of the British Empire into a government rout that saw the British authorities grant all the miners demands within 12 months of the rebellion. The reaction to the carnage extended the revolt from the diggings to the urban centres. The bush telegraph spread the message of the atrocities committed at Eureka in the name of the State. Those in authority soon found that armed force diminished not increased their authority.

Peter Lalor wrote 3 months after the Eureka massacres "As the inhuman brutalities practised by the troops are so well known, it is unnecessary for me to repeat them. There were 34 digger casualties at which 22 died. The unusual proportion of the killed to the wounded, is owing to the butchery of the military and troopers after the surrender."

The people of Victoria knew that the massacre was an attempt to intimidate them. They understood that if the government got away with this type of behaviour, they could find themselves in the firing line. As we approach the 150th celebrations, attempts will be made to whitewash this pivotal moment in the Eureka rebellion, it's important that those of us who are attempting to Reclaim the Radical Spirit of the Eureka Rebellion, don't let the State rewrite history and hijack these celebrations.

Lalor wrote a few months after December 3rd 1854, "the unusual proportion of the killed (22) to the wounded (12) is owing to the butchery of the military and troopers after the surrender." Eureka was pure and simple a massacre. The killing went on for up to an hour after the diggers had surrendered and they occurred up to a kilometre from the stockade. People were killed who had not been involved in the protest, let alone had taken up arms against the colonial authorities.

Lalor wrote a few months after December 3rd 1854, "the unusual proportion of the killed (22) to the wounded (12) is owing to the butchery of the military and troopers after the surrender." Eureka was pure and simple a massacre. The killing went on for up to an hour after the diggers had surrendered and they occurred up to a kilometre from the stockade. People were killed who had not been involved in the protest, let alone had taken up arms against the colonial authorities.

Bodies were mutilated, one diggers corpse had 16 bayonet wounds in it. In one case Henry Powell a digger from Creswick who had his tent up 300 metres outside the stockade was surrounded by around 20 mounted police. He was struck on the head with a sword by "wait for it" Arthur Akehurst the clerk of the peace, he was then shot several times by Victoria's finest, who then amused themselves by riding their horses over his lifeless body. Somehow Henry Powell survived long enough to make a statement before he died.

One of the more memorable eyewitness reports about the ensuing massacre described how 3 soldiers jumped a digger after he had been shot through the legs, one knelt on his chest, one tried to choke him while the third went through his pockets looking for gold. "Foreigners" bore the brunt of the attack. Two Italian miners who had not taken part in the Eureka Stockade, one who had his tent more than 300 metres from the stockade was killed by mounted police and troopers. One was shot as he attempted to get back to his tent. The other who had his tent in the stockade but had not participated in the rebellion was shot through the thigh, as he lay wounded he told the troopers that he would give them his gold if they left him alone. After taking his gold they bayoneted him through the chest putting him out of his misery.

One of the most unlikely targets that met his maker in the early hours of Sunday morning was Frank Hasleham. Frank was a reporter for the Melbourne Morning Herald, a newspaper that had consistently supported the government in its fight against the diggers. Three hundred metres from the stockade he was met by mounted police who welcomed him by shooting him through the chest. As he lay dying, he hoped the "diggers would desist from their madness".

Between 5.00am when the diggers defence had crumbled till 7.00am when the sun brought to light the carnage in and around the stockade, the killing continued. The police were at the forefront of the atrocities burning everything within the stockade and shooting at whatever moved. Even the Irish priest Father Smyth was denied access to the wounded soldiers (some of whom were Catholics) and was forced out of the stockade at pistol point by the mounted police.

At 7.00am it was decided to round up all the diggers left inside and outside the stockade. Captain Pasley the second in command of the British forces sickened by the carnage, saved a group of prisoners from being bayoneted and threatened to shoot any police or soldiers who continue with the indiscriminate slaughter. One hundred and fourteen diggers, some wounded were rounded up. Everyone able to walk was marched off to the camp about 2 kilometres away. Two of the wounded collapsed and died by the roadside. On arrival they were pushed into an overcrowded lockup. Peter Lalor the leader of the revolt, who had been shot in the shoulder, had been hidden under a pile of wood in the centre of the stockade. His presence had not been detected by the military and police and he was "spirited" away by supporters later on in the morning.

At 2.00am on Monday morning, ten hours after 114 men had been herded into a space that was normally used for six, the authorities concerned about the reaction of the people if large numbers of the stockaders died in custody, were moved to the camp storehouse.

By Monday morning the government was faced with the prospect of a revolt in Melbourne. Popular disgust with the massacre that had occurred at Ballarat had turned Victorians against Hotham's government. On the same morning Hotham and his Executive Council proclaimed martial law in and around Ballarat. Hotham met a delegation of "influential" citizens and asked them to organise a defence of Melbourne as all his troops were in Ballarat.

Hotham attempted to blame the rebellion on foreigners and the Irish. Most of the movement's leadership were still at large and out of the 114 arrested only 11 were "foreigners" and around 30 were Irish. By Wednesday the 6th of December, public meeting were being called across Victoria, decrying the governments actions. Newspaper articles also began to appear that condemned Hotham's actions. The Age stated "There are not a dozen respectable citizens in Melbourne who do not entertain an indignant feeling against it for its weakness, its folly and its last crowning error. They do not sympathise with injustice and coercion".

In The Age 5th December 1854, Major General Sir Robert Mickle, the commander of the colony's military forces, put out a proclamation when Captain Wise died of the wounds inflicted at the stockade on the 21st of December 1854, stating that the Eureka stockade was built by 'a numerous band of foreign anarchists and armed ruffians had converted into a stronghold'.

It's nice to know that even in 1854 anarchists were considered to be convenient scapegoats in Victoria.

In an effort to muster support, Governor Hotham presented his case to the Legislative Council on Monday the 4th and the squatters' representatives on Tuesday the 5th. Both "august" bodies threw their weight behind the Governor pledging to support Hotham to the hilt in his struggle "to maintain the law and preserve the community from social disorganisation".

Hoping to bask in the glory, the Mayor of Melbourne called a public meeting to give the people of Melbourne an opportunity to demonstrate their support for authority. Around 5000 people attended the meeting in Swanston Street on Tuesday. When the mood got ugly and the military police and naval detachments guarding the Mayor were in danger of losing control of the meeting, the Mayor closed down the meeting before the crowd could vote on whether they supported the flag of England or the Southern Cross. On Wednesday around 6000 people gathered outside St. Paul's and refused to support the government's action. Across Victoria, meetings were held that called for the release of the prisoners, public representation and liberty and justice.

Within the space of a few days a comprehensive military victory had become a defeat. Hotham, concerned about the possibility of a popular revolt that could see him swept from office, called for military and naval support from Van Diemens Land (Tasmania). Once news of the indiscriminate slaughter leaked out, Hotham's days were numbered. Of the 114 prisoners detained at Ballarat, 13 were eventually charged with High Treason. Three of the 114 detained were Americans. Captain James McGill who claimed he was trained at West Point and Charles Ferguson both prominent participants in the Eureka Stockade, were freed within 48 hours of their arrest. The remaining American, John Joseph an African American, was of no interest to the American Vice Consul who with Hotham connived to give immunity to McGill and Ferguson but decided a black face among those charged with High Treason would strengthen the Crown's case that foreigners not English were behind the rebellion.

Thirteen of those arrested at Eureka were committed for High Treason on the 16th of January 1855, barely six weeks after the Eureka rebellion.

Interestingly, few of the leaders behind the Eureka rebellion were committed for trial, because they were hidden by a sympathetic population that was not willing to give them up for the substantial rewards that the government had placed on their heads.

Those who stood trial for High Treason were Timothy Hayes Chairman of the Ballarat Reform League, James McFie Campbell a black man from Kingston Jamaica, Reffaelo Carboni an Italian who had been involved in the 1848 revolutions in Europe and an anarchist sympathiser who wrote one of the most important books about the Eureka rebellion in 1855 The Eureka Stockade: The Consequences Of Some Pirates Wanting On Quarter-Deck A Rebellion, Jacob Sorenson a Jew, John Manning a Ballarat Times journalist originally from Ireland, John Phelan a friend and business partner of the elected leader of the Eureka rebellion Peter Lalor who came out from Ireland as a young man, Thomas Dignum was born in Sydney, John Joseph a black American who is credited with firing the shot that eventually killed Captain Wise, James Beattie who was about to be executed at the stockade by trooper Rivell when Sergeant Riley heard his calls for mercy and took him prisoner, William Molloy who currently I have no information about, Jan Vannick from Holland, Michael Tuohy a survivor of the Irish potato famine who immigrated to Melbourne at the age of 19 in 1849. He was born in Scariff, Ireland in 1830 and died at the age of 85 in 1915 at Ballarat Hospital from pneumonia and Henry Reid a stockader who stood his ground and fired repeatedly at the military advance on the stockade.

The thirteen were transferred to the Old Melbourne Jail from Bacchus Marsh lockup on Wednesday the 7th of December 1854. They were held in the most vile conditions, fed barely anything and were repeatedly stripped naked and searched. John Price the Inspector of Victoria's prison system and the man who made life so difficult for the prisoners was murdered by a group of convicts three years later in 1857 and some people say "God doesn't exist".

Over the last 148 years the Eureka rebellion has been portrayed as essentially a dispute about mining licenses. Although the mining license issue provided the catalyst for the rebellion, the demands made by the Eureka stockaders went far beyond any questions about mining licenses. Interestingly, the Ned Kelly saga has had much more exposure than the story behind the Eureka rebellion.

When it comes to radical social change, the Eureka rebellion is a defining moment in Australian history. In comparison to the Ned Kelly story, it's a much more important historical event than the Ned Kelly story will ever be. The concentration of attention on Ned Kelly and his gang at the expense of the Eureka rebellion is directly linked to the inability of the Ned Kelly gang to create a political movement that was able to challenge the power of the State. It's one thing romanticising the exploits of a group that was never actually able to mount a serious challenge against the status quo, it's another thing to bring a State to its knees.

The Eureka stockade is a much more radical event than most historians have credited it with. Men and women designed and flew their own flag the Southern Cross, they swore an oath that did not acknowledge God, King and Country and most importantly of all, they took up arms to defend themselves from the unwanted attention of the British government. Their demands were much more radical than they are credited with. The minimum demands of the Eureka stockaders encompassed:

Within a year of the rebellion the colonial authorities met all miners' demands.

Hotham decided to hold separate trials for the 13 accused. John Joseph the Afro-American who was accused of firing the first shot that killed Captain Wise, was the first brought to trial. The government believed that a jury would have no trouble convicting a black man. A number of lawyers came forward to help those accused of High Treason. Butler Aspirall and Henry Chapman appeared for Joseph while the Attorney General Stawell represented the Queen.

The first clash came with the selection of the jury. The Crown challenged potential Irish jurors and publicans. John Joseph sent the court into a spin when he objected to gentlemen and merchants being selected on the jury. No Irish jurors were picked for jury for Joseph's trial. The Crown called two government spies to give evidence, both claimed they saw Joseph in the stockade. Two privates from the 40th regiment claimed they saw Joseph fire the first shot that struck down Captain Wise. The charge against Joseph that had to be proven, was that Joseph had attempted to subvert the authority of the Crown in the colony by wounding and killing her soldiers in other words the Crown had to prove "treasonable intent". The defence lawyers didn't call any witnesses and made much of the point that "a riotous nigger" or a "political Uncle Tom" could have "treasonable intent", leaving it up to the jury to decide if Joseph had any intent to commit treason. The jury returned quickly from their deliberations, finding John Joseph not guilty of High Treason. Pandemonium broke out in the court at the not guilty verdict. The cheering was so loud that Chief Justice Beckett (the residing judge) in a fit of pique, singled out two members of the public gallery and jailed them for a week for contempt of court.

"On emerging from the Court house, he was put in a chair and carried round the streets of the city in triumph" Ballarat Star. Over 10,000 people had come to hear the jury's verdict. When you consider that Melbourne's population wasn't even 100,000, the crowds that had gathered to listen to the jury's verdict were an indication of how important many people believed these trials were.

John Manning a Ballarat Times journalist and former school teacher was the next of the 13 to face the courts on a charge of High Treason. The owner and editor of the Ballarat Times Henry Seecamp, the same Henry Seecamp who was publicly horsewhipped by Lola Montez in the United States pub in Ballarat for criticising her exotic dancing in the Ballarat Times, had been found guilty of sedition and jailed for 3 months a few months earlier. It was common knowledge among the miners and authorities that John Manning had penned many of the seditious articles that Seecamp was found guilty of writing and the authorities expected that he would be convicted by a jury which was chosen from the same jury pool that acquitted John Joseph. Once again the jury did not have any Irish representatives on it, 9 of the jurors were working men.

The only problem about John Manning's case is that the Crown had very little evidence that he had actively participated in the Eureka stockade. It took the jury only a few minutes to find him not guilty of the charge of High Treason. Manning's acquittal was a blow to the prosecution's chances of recording a conviction because Manning was regarded as one of the leaders of the rebellion. He had also been involved in a meeting of the 13 "captains" of the rebellion when the Eureka stockade was thrown up after the march from Bakery Hill on the 1st of December 1854.

John Manning had been in the thick of the rebellion. Inspector Carter had found Manning in the guardroom of the stockade (the armoury), when he led an attack on the tent. He personally arrested Manning and handed him over to Lieutenant Richards of the 40th regiment.

Faced with the problem of a Melbourne jury not wanting to find the accused guilty and with 11 more charges of High Treason to be heard, the Attorney-General asked the courts for a months stay, so that they could review the charges. Hotham was adamant they must stand trial, so the Attorney-General in an attempt to secure a conviction stood down the original jury panel and empanelled a new list of 178 jurors on the 19th of March 1855. This jury panel was hand picked, solid middle class men, who could be relied on to convict the Ballarat rabble that had defied Her Majesty Queen Victoria. Hotham went to bed, secure in the knowledge that the jury would do its job and convict the rest of the accused.

Hotham was becoming a laughing stock, he was verbally abused when he showed his face on Melbourne's streets. Even his own hand picked assistants were beginning to doubt his suitability for the office he held. He needed one conviction, one drawing and quartering to reestablish his authority. His Attorney-General understood his dilemma and did all he could to stack the jury with jurors sympathetic to the government. From the new list of 178 potential jurors, 6 small businessmen, 3 tradesmen, 1 gardener and 2 farmers were chosen to judge Timothy Hayes, a man who all of Victoria believed was one of the ringleaders behind the rebellion.

Timothy Hayes was defended by Richard Ireland, the judge was Redmond Barry, the same Redmond Barry who 20 years later sent Ned Kelly to the gallows. The scene was set for an interesting trial. Timothy Hayes was Lalor's mining partner. He had been the chairman of the final mass meeting at Bakery Hill on the 29th November 1854. He had stood up and whipped up the crowd into a frenzy by calling out "your liberties, will you die for them!!" The crowd roared its approval and burnt their licenses.

Henry Goodenough and Andrew Peters, the two police spies gave their tainted evidence. Henry Goodenough told the court he heard Hayes ask the crowd to fight for their liberties. On cross examination he agreed he had asked other miners to do the same thing. Father Smyth the Catholic priest swore that Hayes had gone to the Catholic chapel during the attack at the stockade. Henry Foster the Inspector who arrested Hayes told the jury he arrested him 300 yards from the stockade and surprise surprise, he had a current miner's license on him. Hayes' wife Anastasia, one of the three women who sewed the Southern Cross flag, was disgusted by the revelations. Fortunately for Timothy Hayes, the jury liked what they heard and acquitted him of the charge within thirty minutes of sitting down to consider their verdict. Once again another prisoner who has escaped execution, was carried through the streets of Melbourne.

Hayes later became the Town Inspector for Ballarat East and was appointed a special constable in 1862. He and his wife Anastasia parted company in 1862, he went overseas to Chile, Brazil and the United States returning in 1866. Anastasia was left to look after their five children Edward, May, Nanno, William and Anne on her meagre school mistresses salary. Hayes returned to Melbourne in 1866 and worked on the Melbourne Railways till he died.

Timothy Hayes' acquittal took Hotham by surprise. He was convinced that Hayes, one of the ringleaders of the rebellion, would have been found guilty. Raffaello CARBONI'S turn came on the 21st of March 1855. Carboni had been at the forefront of the rebellion. He had actively participated in the 1848 revolutions that had swept Europe and had come to Australia to begin a new life. The Attorney-General believed he had a water tight case against Carboni. He had 8 eyewitnesses, 4 police and 4 troopers from the 40th Regiment who would swear that Carboni was in the stockade, attacked them with a pike and shot at them. The Attorney-General also had the services of the two discredited spies, Goodenough and Peters.

To make things more difficult for Carboni, his defence witnesses didn't turn up to speak on his behalf. (Some people say the authorities pressured them not to attend.) Carboni's lawyers, Ireland and Aspinall were able to show that Goodenough's and Peters' evidence had little to do with reality. The other witnesses' stories were much harder to discredit. Sergeant Hegarty of the 40th Regiment swore that Carboni had shot Captain Wise. Carboni swore that he had never seen any of the 8 police and soldiers who had given evidence against him till the day he saw them in court.

Ireland a flamboyant lawyer, who enjoyed the courtroom drama, asked the jury to take into account the consequences of their decision. He told them that if they found Carboni guilty, their decision would mean that under the law, Carboni's dismembered body would have to be hung from the gates of Ballarat. The jury retired to consider their verdict but returned 20 minutes later with a NOT GUILTY verdict. Carboni addressed the thousands of people who had come to support him and hear the verdict. Of all the major participants involved in the Eureka rebellion, Carboni was one of the few to put the miners' side of the story down on paper. On the 1st anniversary of the massacre on the 3rd of December 1855, he gave away 100 copies of a book he had written on the rebellion at the Eureka Stockade - The Consequences Of Some Pirates Wanting On Quarterdeck A Rebellion at Ballarat, the site of the massacre.

(Today original copes of his book are sought after by collectors and Peter Lalor's personal copy sold for over $100,000 last year.)

Carboni had had contact with anarchist ideas and was one of the major players in the Eureka rebellion who wanted a revolution. He left Australia at the end of 1855. He spent some time in India and Palestine before he returned to Italy. Carboni became involved in Garibaldi's campaign to unite Italy and died in Rome on the 24th of October 1875, just 20 years after the Eureka revolt. His first hand account of the rebellion has provided one of the few records of the event from the miners' side.

Carboni's acquittal twenty minutes after the jury retired, should have culminated in the end of the treason trials. Governor Hotham and his Attorney-General William Foster Stawell, rightly believed their credibility with the Home Office in London rested on a conviction, so they insisted that the farce go on, hoping they could record one conviction.

Jan Vannick a "foreign" from Holland, one of the "mongrel crew" took his turn on the stand. After a trial that lasted less than a day he was acquitted in record time. James Beattie was the next miner to face the court. Evidence was given that trooper Rivell from the 40th Regiment, confronted Beattie as he clambered back into the stockade with a pistol in his hand. Beattie dropped his pistol, dropped to his knees and screamed "Mercy! Save Me! Don't Shoot! I am beaten! I will give in!" as trooper William Rivell aimed his carbine at him. Fortunately for Beattie, Sergeant Patrick Riley of the same regiment saw Beattie beg for mercy and told trooper Rivell to take him prisoner. Beattie was acquitted once again in record time. Michael Touhey took the stand the following day. Evidence was given that Touhey was caught escaping from the stockade. Once again another one of the magnificent thirteen was acquitted of the charge High Treason.

Michael Touhey was born in Scariff, Ireland in 1830. He survived the Irish famine, burying many family members and friends. He never forgot that food was being exported from Ireland to line the pockets of English absentee landlords, while a million Irish men, women and children died and a further million were forced to immigrate. On the morning of December 3rd 1854, Touhey was prepared to fight and die if necessary. Although he had traveled 12,000 miles to escape the tyranny of the British government, once again he faced the same tyrants.

Luck seemed to be with Touhey, after side swiping a bayonet that ripped through his clothes, he was arrested and marched to the police camp. On the way to the camp, a soldier tried to cut off his head with a sabre. Touhey's nimble feet saved him once again. After his acquittal he returned to the alluvial diggings at Ballarat. Once the gold ran out, he took up a farm in the Ballarat district between Melbourne and Ballarat. He took part in the 50th anniversary celebrations at Ballarat in 1904 and continued farming till he died at the age of 85 from pneumonia at the Ballarat Hospital in September 1915. He was the last survivor of the thirteen who stood trial for High Treason in Melbourne in 1855.

The last six prisoners Thomas Dignum, James McFie Campbell, Jacob Sorensen, John Phelan, William Molloy and Henry Reed were tried together before young judge Raymond Barry. Stawell the Attorney-General, dropped all charges against Thomas Dignum as the authorities claimed they didn't have any evidence to tie him to the Eureka stockade. The other five faced the music, but within a few hours they were all acquitted. They were cheered as they left the court by the thousands of people who had gathered outside, to ensure justice was not only seen to be done but done.

Of the five who were tried, James McFie Campbell was the most interesting. The Sydney Morning Herald, the only newspaper hat supported Hotham, described Campbell as a member of the "mongrel crew of German, Italian and negro rebels" that was responsible for the Eureka rebellion. Campbell was a black man who hailed from Kingston, Jamaica. Interestingly, Thomas Dignum who was born in Sydney and had charges of treason dropped against him, had been actively involved in the rebellion on the 3rd December. It's possible Stawell tried to cut his losses by removing Dignum from the last treason trial because he believed a local jury would never convict a native born Australian.

The Attorney-General Stawell, felt that he had a better chance of convicting three, Irishmen Molloy, Phelan, Reed, a Jew Sorensen and a negro Campbell if charges against the only native born Australian among them Thomas Dignum were dropped. Phelan was a friend of Peter Lalor who rumour had it, had been involved in the establishment of a sly grog shop at the corner of Latrobe and Elizabeth Street in Melbourne in 1853. Although Henry Reed was acquitted of treason, Sergeant Major Michael Lalor of the mounted police, was shot at with a long piece by Henry Reed, after Michael Lalor had shot Peter Lalor in the shoulder.

The only interesting aspect of the trial was the judge's attempts to bring God into the courtroom. Before the jury was sent away to consider its verdict, Barry took the opportunity to tell the jury (after a thunderstorm temporarily halted proceedings) that "the eye of heaven was upon them and their verdict". Even the involvement of the deity by Judge Barry in the proceedings didn't sway the jury, hey found the last five prisoners not guilty of treason and the whole sorry judicial farce came to an end.

The acquittal of the 13 defendants charged with High Treason, turned the tables on Hotham and his scurvy crew. Although Hotham took the blame for the judicial farce, the Attorney-General William Stawell was ultimately responsible for this whole sorry saga. While men and women who were involved in the Eureka stockade are largely forgotten, a Victorian regional town 'Stawell' still bears the Attorney-General's name and Australia's most prestigious and well know professional footrace "The Stawell Gift", honours the memory of the man who engineered the butchery which occurred at Ballarat on December the 3rd 1854.

Stawell not only goaded the diggers into taking up arms and organised the military response, he was also responsible for attempting to pervert "the course of justice" by manipulating the jury system and by encouraging the virtual army of spies he had working for his department, to perjure themselves at the trials of the 13 accused.

Hotham paid the ultimate price for his rigidity and his role in the Eureka rebellion. Lord John Russell from the London Colonial Office, scolded Hotham for not following his advice and charging the 13 with High Treason. The London Colonial Office did not believe a local jury would convict the men of the charge. Broken in health, Hotham had been forced by November 1855 to send his resignation to the Colonial Office. Hotham died on the 31st December 1855 as a result of a "chill", some say a "broken heart".

The Legislative Council was asked by John Pascoe Fawkner, one of Melbourne's founders, to set aside a thousand pounds (a colossal sum in 1856) to build a monument to Sir Charles Hotham. Peter Lalor the Eureka stockade leader, had been elected to the Legislative Council, opposed the motion stating that "Hotham had a sufficient monument in the graves of those slain at Ballarat". The motion was passed and a thousand pounds was set aside to build a monument in Hotham's memory.