As I type this Easter weekend my family have loaded their cars and motored to the country to enjoy the four day holiday. In preparation, they have had to travel some kilometres to stock up on provisions for the trip, including a re-supply of bottled gas for their cooking. They could hardly imagine life without a car.

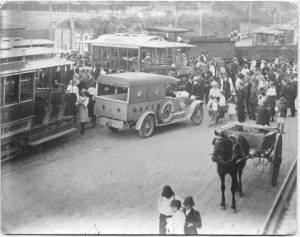

This is very different from the 1920s. Brisbane was one of the first

Australian cities to have electric trams (from 1897) but they were

supplemented by horsedrawn trams for many years. Inter-city transport was

dominated by the railway and shipping but distribution from the

goods-yards to the stores in the suburbs was mainly by horses.

This is very different from the 1920s. Brisbane was one of the first

Australian cities to have electric trams (from 1897) but they were

supplemented by horsedrawn trams for many years. Inter-city transport was

dominated by the railway and shipping but distribution from the

goods-yards to the stores in the suburbs was mainly by horses.

In the 1920s Uncle John Murray used to drive a lorry, not a motor lorry, but a lorry pulled by a team of horses. He used to work for a big transport company, Bryce's, at the corner of Albert and Alice Streets, opposite the City Botanical Gardens, and the space now occupied by the Parkroyal Hotel. (It was not far from Brisbane's most famous Albert Street brothel in those days).

My brother Kevin has shaken my memory concerning Ted's motor bike. It seems that the workers' compensation that Ted received for his fractured skull was first invested in a motor truck. But Ted's head couldn't stand the pounding and vibration of the truck. It wasn't only the poor conditions of the roads but in those days the pneumatic tyre wasn't in common use, especially for heavier vehicles. Indeed, such heavy trucks had solid rubber tyres. Thus, the reason for Ted's motor bike.

Kevin also reminded me that when Ted had the motor bike he used to take Aunt Nell on the bike. If it was raining Nellie would open a brolly to protect herself and Ted from the rain and she would end up obscuring Ted's view, a real traffic hazard, but fortunately there wasn't so much traffic in those days.

While the horse for personal transport was rapidly giving way to the tram and train in suburban Brisbane, there were still some who preferred the horse-drawn sulky. Mrs. Horn, at the top of Waverley Road, often passed our place on her way to town and would kindly offer to carry a passenger. A couple of times she gave me a lift on my many trips to the Mater Hospital.

The ice-cream man used to come around ringing his bell. His cart was pulled by a goat. The butcher, the baker, the fish-monger, the green-grocer, all had carts pulled by a horse. The milkman (with fresh, un-pasteurised milk) used to call, when Sally wasn’t milking, with measured pots giving a quart, a pint, a half-pint and a quarter-pint to fill your billy-can from the milk can's tap on his cart.

Domestic refrigerators were unheard of in those days. Most homes had an ice-chest - a cork insulated box with an upper chamber that would hold a standard block of ice which you wrap in newspaper to make it last, below which was the cold box to keep the butter, milk, meat and other perishables. Hence the ice-man would have a roaring trade in the summer.

Sundry other callers, such as the man selling clothes props, would travel around in their horse and cart. I understand that In the 1920s even the garbage and sanitary men used to provide their services by the horse. Can anyone confirm ?

ADVENTURE

I now recall many adventures we had as kids that are not enjoyed these days by children. One adventure that we all looked forward to was the celebration on the 7th November - Guy Fawkes night. The Giffins always had the biggest bonfire in the district, fuelled, not only by a great quantity of wood, but also by stacks of old tyres which burnt like oil (and filled the air with soot); but our parents didn't let us go to the Giffins in the early days. Mum and Dad confined us, wisely, to throw-downs, sparklers, Tom-thumbs and a few bigger bungers in the hands of Dad.

In good time we graduated to older childhood and our own bon-fire and we used to bring bush wood in for the weeks preceding bon-fire night. It was said that if you didn't guard your wood it would be stolen or prematurely set on fire by some gang or other; no such thing happened to our preparations.

In the late 1930s our parents allowed us to attend the Giffin's bon-fire. On one such occasion brother Leo was jumping over some tyres waiting to go on to the fire when he misjudged his footing and ended up with a broken leg. While waiting for the ambulance Kev, always a joker, was teasing Mum on what would happen to Leo in hospital.

I did things that, on looking back, were terribly dangerous - such as breathing fire out of my mouth - a great spectacle. The danger was not that I would catch on fire but, as I found out later, I could have killed myself in taking into my lungs the common substance that I used to produce the fire. I dare not mention the substance for fear that some young person will read this and attempt the trick. While it was good fun for us and real harm never befell our family, I'm pleased that fireworks (and the bon-fires) are banned for the sake of children (and the world).

Opportunity for kite flying is much more limited for kids today because of the density of buildings and other structures, such as pylons, wiring, etc. Again, the Giffins were the masters of kite making and flying; but the Englarts put on a credible show.

Our first good kite was a bought one - a Sky Raider - more than a metre high and almost a metre wide. I could only guess how high they flew but they would extend the ball of string some hundred metres long; so high they were a speck in the sky. We used to thread pieces of strong paper on the string and watch them work their way up the string to the kite.

Every summer was lorikeet time. Swiftly flying, usually in great flocks they would descend into the suburbs. The commonest bird was what we called "the greenie", green-backed birds with a red or yellow collar and some red on the underwing. Like most boys of the period we used to trap "greenies" in a little over a metre cubed, fitted with two or four traps built into the top of the cage. You need to start with a couple of birds which call other birds down and the traps are tripped when the bird's weight lands on them. You need to watch your fingers as you transfer the birds from the trap to the cage. They've got strong beaks.

Much favoured was the rainbow lorikeet, a red-breasted, blue-headed bird with a pale greenish-yellow collar, a red beak and blue bars on the belly. We used to call them "blueies" and never had the opportunity to catch them. Blueies and greenies are wild birds, never make pets, and quickly die in captivity. Such is our shame !!

Now that it is illegal to trap native birds and people now cultivate more native plants the wild fauna is coming back to the cities; even flocks of greenies can now be seen at Red Hill, three kilometres from Brisbane. They upset some residents with their squawks and their shit. For me they are a consolation for my past.

DOBOY

Ted's brother George married Dot Murphy and Ted's sister Mabel married Dot's brother Bert Murphy. Dot was seriously crippled in that one leg was shorter than the other. A small woman, it was painful to watch Dot walking, alternatively throwing her light weight from side to side, from her longer leg to the shorter one. George and Dot didn't have children, for whatever reason. I'm sure George would have loved kids and our family seemed to have been adopted by him as his own.

Ted had a falling out with Dot and she wasn't welcomed in our house for years. George and Dot often had rows and George more than once visited Ted, and wept, for the comfort that only a brother can give a brother. As I mentioned, George had a terrible stutter, but, with a few beers, George could recite a poem and sing faultlessly. He was the life of the party.

In time, Ted once again allowed Dot to visit and George and Dot invited Kevin and myself to visit them at Doboy. I was about thirteen and Kev was twelve at the time. We got the train down and you had to instruct the driver to stop at Doboy because it wasn't a regular stop. George was a watchman and caretaker at the bacon factory. The mango trees on the caretaker yard were the biggest I've seen. They were the local species and not as nice as the mangoes you get today. But I liked them (if I could dodge the fly grubs).

On visiting the factory, the first thing that strikes your senses is the smell - the stink - of the pigs, or at least, of the pig shit. But I guess it is no sweeter, or any more offensive, than any other kind of shit in quantity. You all know what its like when a cattle train passes by, except this smell is continuous. You can get used to it, otherwise we wouldn't have workers who, day-in, day-out, produce our ham and bacon.

The second thing that strikes your senses is the noise - the squeals - of the pigs. It's not as though the pigs are suffering - its just what pigs do. Then the pigs are let into the slaughter-pen, just two or three at a time. The slaughter-man has a killing tool that has a hammer on one side, and a knife on the other. He brings the hammer down to stun the animal, and, in a continuous sweep, brings the knife blade up to cut the pig's throat.

There is blood everywhere, and it seemed to me, that it would be very dangerous for the slaughter-man with his Wellington Boots on the slippery bloody floor. I don't remember much more of the factory, but there was steam and hot water everywhere, as well as the boiler house that supplied the energy.

Aunt Dot did her best to please Kevin and myself. She cooked up some bacon bone soup and it seems that we had the saltiest bacon bones that ever came out of the Doboy bacon factory. Too well mannered to complain of Aunt Dot's effort, we suffered in silence.

Now George and Dot didn't have the electricity supply to the house and the

only lights were hurricane lamps and candles. There was Kev and I

stumbling around to light a candle so that we could find some water to

quench our thirst. If my memory serves me well I think Aunt Dot took us

down to the sea at Manly.

Now George and Dot didn't have the electricity supply to the house and the

only lights were hurricane lamps and candles. There was Kev and I

stumbling around to light a candle so that we could find some water to

quench our thirst. If my memory serves me well I think Aunt Dot took us

down to the sea at Manly.

As they grew older George and Dot used to barely put up with each other (sadly, as many couples do with time). In later years Kev used to take Ted, and sometimes myself, around to visit George and Dot. Dot was confined to a wheel chair, constantly complaining about George, who did what was absolutely necessary for Dot's needs, but little more. Ted and George were as close as brothers can be and George was extremely generous in his will to my brothers and sisters when he died at ninety.