A photograph of Chummy Fleming is available from the State Library of Victoria Multimedia Catalog. [J. W. Fleming. Union Pioneer] Library Record Number: 962444.

A photograph of Chummy Fleming is available from the State Library of Victoria Multimedia Catalog. [J. W. Fleming. Union Pioneer] Library Record Number: 962444.

Available Writings of J.W. Fleming

John Fleming, generally known as 'Chummy', was born in 1863 in Derby, England, the son of an Irish father and an English mother who died when JW was five years old. His (maternal) grandfather had been an 'agitator' In the Corn Laws struggle and his father also had been involved In Derby strikes.1

' ... At 10 he had to go to work in a Leicester boot factory. The confinement and toll broke down the boy's health and whilst laid up with sickness he began to reflect and to feel that he was a sufferer from social injustice...'

Fleming attended the free thought lectures of Bradlaugh, Holyoake and Annie Besant, before coming to Melbourne. Jack Andrews, an anarchist colleague, recorded his early period in Australia this way:2

'...(He was) 16 when his uncle invited him to Melbourne. He arrived in 1884 and for a time he was a good deal more prosperous than later, getting work as a bootmaker'.

He attended the 1884 (2nd Annual) Secular Conference held in Sydney, but more importantly was soon regularly attending the North Wharf Sunday afternoon meetings, illegally selling papers there. The regular speakers at the time were Joseph Symes, President of the Australasian Secular Association, Thomas Walker, another free thought lecturer, Monty Miller, a veteran radical, and W.A. Trenwith, an aspirant politician, bootmaker by trade.

Fleming's prosperity did not last long, as by early 1885 it appears he was already in the ranks of the unemployed, perhaps because of his role in a lockout, 3 and graduating to the platform as speaker in his own right. Via Andrews, he described his first arrest:

'... I was amongst the unemployed. Mr White finished a violent speech concluding with remarks about Brutus, and we started in procession to the Treasury buildings, with a banner on which was 'Bread or Work'. Immediately we arrived the police attacked us. Messrs. Williams, Boon and de Ware were arrested, and I received a summons. (The others were) fined'.

This summons appears to have been issued by the Melbourne Harbour Trust for trespassing on their North Wharf property. Discharged on account of his youth, and advised 'to stick to his last by the magistrate Mr. Panton, he was back on the Wharf the following Sunday where, Andrews says, he stuck to his comrades by collecting the money to secure their release.

' ... Afterwards he went to Ballarat for about six months, where he worked as a bootmaker and took part In the local free thought movement and had the experience of being stoned by bigots In the main street along with another agitator named William Lee ... '

He was elected Secretary of the Ballarat Branch of the ASA, but by August, 1885 was back in Melbourne where he was nominated for the ASA Executive. 4

Within the ASA he did not follow his Anarchist Club colleagues in totally repudiating Symes when that person tried to distance himself from Anarchism following the Haymarket furore and the Club's establishment in May, 1886. He appears supportive, initially, at least of Symes' efforts in related struggles such as freedom of speech, and not immediately Interested in Anarchism or the Club. Until a 'People's Forum' was permanently organised at the Yarra Bank, attempts to conduct debates at public spaces such as the North and Queen's Wharf areas were constantly under threat from police, bigots and toughs. Free Speech campaigns, 1885 to 1890 provided Symes, Fleming and numerous others with their first experiences of Melbourne arrests and threats of arrest. 5 Fleming had tremendous drive and enthusiasm and carried agitational ideas into practice where others held back. He didn't have Andrew's intellect or writing ability, or David Andrade's single-mindedness about mutualist-anarchism, the dominant strand in the Club early on, but he had great feeling for practical politics and worked with whatever materials were at hand. This has made his early philosophic evolution somewhat difficult to track and his commitment to and understanding of anarchism difficult to assess.

During the early Club meetings he perhaps shared David Andrade's ideas but later on became more closely associated with the communist anarchism articulated by Andrews, Larry Petrie and Robert Beattie. In August, 1886, as a result of arrests of leaders of the unemployed campaign, Fleming 'promoted and conducted' the first Anarchism meeting held on the Wharf. 6 Such meetings, combining theory and pragmatic concern with the issues of the day then became a feature, with 'Chummy' closely identified with both for the next 60 years at different locations.

Haymarket protests and memorial meetings were regularly organised by him. In 1889, with Andrews he addressed the Richmond Young Men's Society to try to counter the heavy broadsides against anarchism in general and the Haymarket group in particular. 7

With the demise of the Anarchist Club's Co-operative Home in late-1888 as a result of the split within the Club over the question of communism, individualism and the nature of revolution8 the 'socialists' of Melbourne combined to establish a Melbourne branch of the Australian Socialists League which had, as in Sydney, strong anarchist leanings. There were still differences of opinion and Fleming continued to work outside the ASL with those anarchists like Andrade who opposed the communist strand. He played a major part in the establishment of the ASL, opening the first meeting, 9 January, 1889, with an address on the objects of the League and readings from Kropotkin's 'Appeal to the Young'. 9 He seemed to see the ASL as a branch of the MAC, and he contributed to the last issue of the Club's paper, 'Honesty', and probably attended the last meeting as David Andrade tried to keep it going in early 1889, before allowing it to go into recess for 16 months. Fleming also attended the Club 'Reunion' in July, 1890. It is not clear what part he played in the formation of the Social Democratic League, July 1889, which superseded the ASL through the efforts of Rosa and Flynn, two non- anarchists. Fleming is reported as a Committee Member in June, 1891, when a re-organised SDL was discussing a possible Co-operative Company. 10

His involvement with wider issues also continued. In late 1889, as an organiser of the Sunday Liberation Society, and addressing the crowd on the need to open the Public Libraries and Museums on Sundays, Fleming concluded by saying that he was 'Just going up to the Public Library (closed by church pressure) to look at it from the outside'. Many from the meeting followed him: 11

'...On the few Sundays following, the ceremony ... was repeated with set purpose but with smaller numbers. Then came a Wednesday meeting near the Working Men's College...'

Andrews tells of this meeting appointing a deputation of five to Parliament House. But many from the crowd followed, and others joined in till there were 6,000 people surging along the street. The police tried to stop them, to break up the procession, but the crowd surged up the steps, where they were stopped. Failing rain dispersed them and later newcomer Rosa, Fleming and John White received summonses for 'taking part in an unlawful procession'. Each was imprisoned for a month. The movement achieved success but the libraries etc. weren't patronised enough, and eventually closed again on Sundays for 40 years.

A letter written subsequently to the 'Liberator', on 4 January, 1890, from jail (for 'obstruction') says that he, Fleming, had been studying the prison regulations and found that the sanitary arrangements were less than required. So, he stopped the Governor on his weekly rounds, 'lectured him for an hour' whereupon the Governor ordered immediate improvements'. 12

Yet another initiative for which Fleming is credited is the first collection in Victoria for the relief of the striking London dockers, eleven pounds. "The movement spread and it is a matter of history how many thousands of pounds were sent from Australia".

One of the most surprising pieces of evidence for Fleming having a wider view and, most importantly, a recognition of the part played by individuals in mass reform, is his concentration in MAC (Melbourne Anarchist Club) debates on women's rights and the need for sexual freedom. Not a great paper giver, he is first recorded leading a debate in September, 1886 and in October he spoke for 'Free Love'.13 The debate had been adjourned from the previous week so that 'ladies' could participate in what had proved to be a 'stimulating discussion'. On the Sunday preceding 27 February, 1887 he spoke on 'The Subjection of Women', and continuing his interest, on 'Marriage, Prostitution and the Whitechapel Murders' on 15 December, 1888.

The as-yet-unsighted 'Liberty' pamphlet 'Free Love - Explained and Defended' issued by the Club without the author's name in 1886 or 1887, may therefore be Fleming's, or a resume of the discussion in September-October, 1886, but is most likely to be David Andrade's as all the others but one are.

It appears 'Chummy' never married and I have no information on any romantic or sexual interest in his life.

When the movement for an Australian Republic prompted meetings in Melbourne, in 1888, at which even Monty Miller spoke in support, 'Chummy' asked the question, 'What will it do for the workers?' dampening the enthusiasm of quite a few. Nevertheless in 1892, he was quite prepared to support an anti-Royalty resolution before 4,000 people on the Yarra Bank, where his 'stand' was already recognised as an institutions.14

Each year, around the onset of winter, the numbers of homeless, destitute people became more acute and tactics were adopted by agitators as seemed appropriate. Fleming and John White were mainstays of this struggle from at least 1885 to 1900. Some incidents cannot be dated exactly:

'One of Fleming's own devices which, if it could have been carried into effect might have been at any rate a means of calling attention to the distress existing in Victoria, was to have the unemployed marching in the Eight-Hours procession with a special banner, but this was objected to, and did not come off, and as only a small number of unemployed were ready to take part in the manner he wished, it is quite possible that the effect might have been just the reverse of what he intended...'

A letter from Fleming in 'Labor Call' 6.4.1933 refers to an unemployed meeting and march, which perhaps is 1889:

'...The unemployed meeting was held on a piece of land near the Workingmen's College. At the conclusion of the meeting, old John White and I carried the calico banner which had written on it: 'Feed on our flesh and blood, Capitalist hyena; it is your funeral feast'. When the unemployed arrived at the Trades Hall they were attacked by unionists. During the fight the banner was destroyed. The police came and ended the fight ...'

On an earlier occasion, during August, 1887, 'Chummy' had work but that didn't stop him addressing a crowd of 2,000 unemployed men, in rain and cold, and with John White, leading a deputation to Mr. Nimmo for work. The next week he denounced the MP's who had boycotted a meeting at the Temperance Hall for unemployed, and announced he was going to Ballarat for a further meeting. Fleming's first recorded action with 'his' union, the Victorian Operative Bootmakers, (VOBU),15 was an amendment he moved on 21 June, 1886. The second reference was not till November, then there Is a gap to 17 February, 1890, when he received his first nomination as VOBU delegate to the THC. He was again just out of jail, indicating why there were so many gaps. He does appear to be acting as organiser for the union during September and October 1888, and collecting 1/- per week levies for the Northumberland (NSW) miners then on strike.

From 1890 his union activities clearly were very important to him. He rarely missed a meeting, despite his other activities, unless detained 'at Her Majesty's Pleasure' or ill, until he was finally expelled from the THC in 1904, ostensibly for disloyalty, but in reality for being independent minded and espousing anarchism. His unionist conscience role went into high gear in 1890 when he opposed Trenwith, who was quickly rising to leadership of the emerging Victorian Labor Party, about working conditions, and accused the moderate THC bureaucrats of 'working with blood-sucking capitalists.'

It is possible that he was unemployed because of blacklisting through a lot of this period. His politics certainly made him invaluable to the 'Out of workers', but a thorn in the hands of Trades Hall officials and opportunist 'labor' politicians who apparently failed to see the connections between trade unions and the unemployed.

Dr. A.G.Serle In his article 'The Unemployed Movement of 1890' refers to the unsuccessful work of the Social Democratic League with the unemployed in 1889 and to 'several thin meetings' organised by Fleming In 1890. He says the movement took on a different tone when Rosa took it up in 1890, and led a 'highly original campaign of protest'. His 'highly original' strategy is no more than Fleming's and others' tactic of strolling processions, but Serle like many academic researchers, obviously hasn't done his homework.

Serle also referred to the very strongly supported 'Anti-Unemployment League' which 'for years had campaigned' for a free labor exchange. Elsewhere, Fleming is credited with beginning the Anti-Unemployed League in 1889, and Rosa the Labor Liberation League in 1890, which Serle only just manages to mention as getting 'little support'. He credits Knipe and Carpenter with leading the Anti-Unemployed League.16

As it happens, Carpenter quickly disappeared altogether and both Knipe and Rosa were shown to be opportunists, the first going to jail for fraud, the second lobbying for Parliament under various disguises but consistently failing to impress. It is also possible that Rosa was an establishment spy and agent provocateur. Both in any case are fly-by-nights as far as the unemployed are concerned, while Fleming and John White are consistent campaigners.

In August, 1890, the unemployment movement was overtaken by the Maritime Strike and radical and anarchist focus shifts north. Rosa 'drops out', ostensibly for 'business reasons', and many agitators were forced to leave town to find jobs. Fleming chooses to stay.

'Chummy' is credited, with Petrie, with bringing the semi-secret Knights of Labor to Melbourne. This is usually shown by way of a Petrie called public meeting in October, 189017 on the occasion of the visit of W.W.Lyght, U.S. Knights of Labor organiser to the antipodes.18 Churchward suggests a united front operating around 1890-3 between the Single Taxers, Knights of Labor and the unemployed against the Protectionist bureaucrats of the T.H.C. and certain sections of the P.P.L. movement. Churchward insists that Fleming was one of the two chief spokespersons for the Knights of Labor in Melbourne up to 1895 though he also records19 Fleming saying that the "Knights of Labor had little influence because of ceremonial mumbo-jumbo". Fleming struggled to have the Knights of Labor admitted to the 1891 Labor Conference and to have it affiliated to the T.H.C. in 1893. It was opposed affiliation, particularly by Trenwith, on the grounds that as a secret organisation it could not be organised industrially. He gave a figure of 30 members, which Fleming did not dispute at the time. He attempted to have the constitution of the T.H.C. amended to admit the Knights of Labor but lost the voter.20

The point at error in the Churchward story of the Knights of Labor is its arrival in Australia. Lyght was in Melbourne by July, 1890, perhaps to organise branches, but an Assembly of the Knights of Labor had been established in Melbourne in June, 1889. Andrews was not impressed:

'The Knights of Labor is alright for anyone who had no ideas of the struggle between Socialism and Capital but no good for Socialism'.21

Andrews was then sounding out the possibility of establishing a Communist-Anarchist group, as the A.S.L. (Melb.) broke up. Certainly the program of the Knights of Labor as summarised In 'Labor's Pioneering Days' isn't quite as bad as Andrew's assessment, but it is certainly not anarchic:

Internationally, anarchists had long been associated with the Knights of Labor. In the USA the Knights 'officially' adopted the Single-Tax philosophy while still wrestling with the question of anarchist socialism; thus the single-tax debate became the vehicle for the thrashing out of the arguments between the centralisers and the decentralisers. In Melbourne virtually nothing is known of the Knights from June, 1889, until May, 1892, when Fleming, representing them, chaired the first public, outdoors May Day gathering in Melbourne. Meetings which can be called May Day Meetings had been held in 1890 and 1891 in the parliamentary rooms of radical MP Dr Maloney with Fleming as Treasurer of some sort of celebration committee. 1 suspect that the 'Little Doctor' chaperoned the early Knights meetings also. Fleming supported Max Hirsch, President of the main Single Tax organisation In Australia, in the VOBU22 from March 1891 beginning a personal association lasting at least until 1896.23 Because of the people in attendance at and supporting Fleming at the 1892 May Day gathering and the people involved in the related groups it would seem reasonable to suppose a loose radical / libertarian coalition operating on a number of fronts.24

In September, 1890 Fleming was elected for the first time to be delegate of the VOBU to the THC, but he continued his lack of concern with the Eight-Hour Day celebration regarding It as a sham. Twelve months later he was elected, unopposed, President of the VOBU for a 6-month term, and for a similar period as President of the Fitzroy branch of the Progressive Political League, the fore-runner of the ALP. Around the same time also, the Democratic Club in Lonsdale Street resurfaced, as a gathering point for radicals.25

Fleming, in the V.0.B.U. and T.H.C. supported inter-colonial strikers, female organisation, and agitation for piece work rates as opposed to a minimum wage which the employers were after. On a number of occasions he as President, asked leave to vacate 'the chair' at V.O.B.U. meetings to attend 'urgent business' elsewhere. This would appear to be largely P.P.L. business, but could have been less public activity. Certainly 1891 Is a comparatively quiet year for Melbourne, especially for J.W.F. Then, there occurs a great burst of 'street' activity, perhaps indicative of a period of clandestine organisation, or else just frustration and anger.

Firstly, pre-dating the Active Service Brigade In Sydney was the 'Industrial Army'. The 'Australian Workman' for December 5, 1891 has the following item probably from Fleming:

'The very latest here is the 'Industrial Army'. It put out an announcement on Thursday, 'Reading of the Articles of War Mobilisation of Troops'. As soon as the Army is sufficiently strong, Society on the Bellamy basis, is to be established in Victoria. Then it will march north to the redemption of N.S.W. and Queensland. On Sunday afternoon they drew up in line of battle at Studley Park. They called to their ranks all workers irrespective of occupation. They would organise men politically and industrially. They would have a labor sheet and a Labor Bureau, through which members could get employment free of charge. Next week they promise to have a march past, a first class band and a big banner.'

Needless to say the grandiose aims remained unachieved. The subsequent appearance however of the Salvage Corps battling bailiffs, police and landlords to seize back furniture of families unable to pay rent suggests where the energy was going by the winter of 1892. Fleming's suspicions about Rosa had in February come to a head as the two competed for pre-selection in the Fitzroy PPL. Although the contest eventually became physical and though both failed to gain pre-selection the lasting penalty was the stigma attaching to anarchism as conservative candidates and persons with scores to settle with Rosa heaped abuse on him and by association all labor reformers, continuing the 'anarchist' hysteria generated by the Haymarket trial and execution. In the short term Fleming also lost the Presidency of the Fitzroy PPL.26

The conservative opposition alarmed, began to retaliate directly with Fleming as a prime target. At an April Fitzroy Town Hall meeting called to discuss the election of 'labour' members of parliament, a certain Mr Best, a lawyer and M.L.A. for the area said 'agitators of the Fleming type should be exterminated like rabbits'. Fleming got up to reply, was thrown off the platform, rose again with help, and moved a motion, that was passed, to the effect that Lawyer Best and Capitalist candidate Tucker were unfit to represent the workers. Outside the hall a further meeting was held, 400 people were enrolled in the P.P.L. and only then did Fleming go home to bed where he remained for a week with a sprained ankle and a bruised hip.27

Reports of the salvage agitation, which continues until the end of July, contain more mentions of grass-roots initiative than before or later. Women hold their own organisational meetings and are more prominent while the gap between the militant unemployed and the protectionist THC bureaucrats becomes far more obvious. The police often intervene, Trenwith, recently elected leader of the Victorian Labour Party, is publically repudiated at Fleming-chaired meetings, groups forcibly recover furniture from warehouses, and canteens and soup-lines are established as part of self-help networks. In all of this Fleming's influence is obvious. He was also working on behalf of the Broken Hill miners then on strike,28 actions stepped up when union leaders were arrested and jailed in Septernber-October.

Early in 1893 he worked with Mrs. Rose Summerfield from Sydney, originally Rose Stone, from Melbourne, reorganising the female bootmaking machinists. Complaints against him to the Trades Hall Council and V.0.B.U., generated by his attacks on do-nothing 'labor' representatives were effectively neutralised by a V.0.B.U. meeting clearly on his side.

At a Knights of Labor meeting in 1893, Chummy moved the motion for what was subsequently the first May Day procession in Melbourne. At the meeting after the march, Max Hirsch, President of the Single Tax League officiated for the 5,000 people present and heard delegates from the Knights of Labor (Fleming), the Democratic Club, the Single-Tax League and the Unemployed move motions. Chummy's motion read:

'That this meeting demands legislative recognition of the absolutely equal rights politically of every adult member of the community; strenuously protests against monopoly and privilege in every guise; and that while declaring the solidarity of the interests of all workers everywhere, pledges Itself to strive for the substitution of a co-operative for the present immoral wage system of labor'.

W.Dudley Flynn and Dr. Maloney are also rightly credited with being centrally Involved in the organisation of this first May Day march, but no-one has matched the consistency of Chummy's participation thereafter. At least into the 1940's he was a feature every year the march was held, and from about 1905 his flag 'Anarchy' and his bell were associated with it.

He travelled to England in July 1893 at his aged father's request to see him, and in November, back in Melbourne reported on UK conditions particularly with regard to the introduction of machines and the replacement of men with women and boy-labour. He took up his Yarra-Bank meetings again and spoke regularly elsewhere. During 1894, '95 and up to April 1896 he spoke up to four times a month on behalf of the Single Tax. Abruptly, these meetings stop, coinciding with Jack Andrew's return south. Then one meeting in October and one in December when they stopped for good. 'Beacon' January 1896, rejects a letter from Andrews critical of the Single Tax and encourages Fleming not to 'slip back' to anarchism. His involvement with trade unions affairs continued, he being partly responsible for the Executive and Co-operative Committee of the V.0.B.U. recommending in June 1895 that the V.0.B.U. adopt the principle of Village Settlement and Co-operation. He also continues to press for a co-operative boot factory. Not a lot is achieved in these areas,29 mainly because of a lack of resources.

In September that same year, at a very big meeting at Melbourne Town Hall to consider 'the sweating evil' he and John White moved a motion that the Mayor, Sir Arthur Snowden who was to chair the gathering, not be permitted to do so because of remarks he had made supporting very low wages. Upon their resolution being carried, the Lord Mayor ordered the hall cleared and the lights turned out. 'Tocsin' (Andrews) for 27 July 1899 suggests that because of this action, White and Fleming forced words to become deeds and brought the Factories Legislation 'whose fame is worldwide'.30

Towards the end of 1895 with White and Andrews, he, Fleming, participated in an attempt to revive the Melbourne Anarchist Club. This came to nothing. Crowds had dwindled also on the Yarra Bank, but authorities continued to harass speakers.31

No mention of Fleming appears In reports of the 1896 May Day events, but in 1897 he is back again. In that year, Trenwith appeared to be instrumental in having him dismissed, forcing him to open his own bootmaking shop. This hold occurred in similar fashion three years before. From V.O.B.U. records it's clear that the bootmaking industry and unions are in a bad way and 'Chummy' is not getting much support in battling against the structural changes taking place or the attempts (usually successful) by employers to peg or reduce wages. He reported to the V.0.B.U. in August 1897 urging unions to support the unemployed and continued his attacks on Trenwith, some of which end in physical clashes.

In 1898 he led the May Day procession down the footpaths in the face of a ban on street marches by the Melbourne City Council. In 1899 along with delegates from the Women's Land Reform League, the Village Settlers Association, Our Fathers Church, the Sunday Free Discussion Society and the Unemployed Committees, he organised the march and prepared resolutions.32

In July, 1899 he and John White were arrested for selling the workers' paper 'Tocsin' on Sunday, becoming embroiled in an attempt by the detective force to close down a paper which was investigating their involvement with sly grog and betting shops.33

Later in the year he delivered a eulogy to Henry George, Single Tax guru, despite 'Tocsin' having pointed out that George had repudiated the Haymarket 12 at a time when he was in a position to mobilise great support.

In his bootmaking work he is described in 1899 as a 'maker' not a 'finisher' but as Merrifield says, he still found employment difficult to get, so by 1902 he again had his own shop, in 6 Argyle Place, Carlton. This remains his home and workshop until his death. To take what seems an average year for his union involvement, the records for the Operative Bootmakers Union for 1889 show Fleming elected that year to the 8-Hours Committee, nominated also for the new union executive (was on old executive) and elected a T.H.C. delegate.34 Subsequently the same year, he was elected to the executive of the Trades Hall Council.35 In that position he agreed with other speakers that unionism is on the decline in Victoria and said his own trade was in a very bad way with union members suffering great distress. The T.H.C. adopted his motion to appoint a Committee to devise re-organisation.36 The 'Tocsin', for 11 July 1901 records that the Organising Committee had managed to bring a number of unions into existence and strengthen many old ones.

A letter from J.W.F. in an 1899 Tocsin37 shows another area of his agitation. He asks the paper to note the release of Sarah Robertson whose only crime was poverty (she then 'abandoned her child'). Fleming, White, Edwards, and Herold, assisted by Fitzgerald, Miss Purnell and Mrs. Beeby managed to get her sentence shortened by five months. When she came out she was 'skin and bone'.

In 1901 he is reported to be very ill, Andrews for one38 believing he would not recover. But he does, with the aid of money raised for him39 and gets straight back into work, particularly as chairperson of the unemployed movement. He and White were receiving donations for relief and Fleming was part of a deputation to the Lord Mayor, in April 1901, with Labor M.P.'s, for permission (!) to have a May Day Procession. The Lord Mayor refused their request for Sunday, but on Chummy's request grants a Wednesday. Fleming's central position is acknowledged by his being given the task of moving No.1 Resolution on No.1 Platform (opposing war, wagedom, etc, sending fraternal greetings, etc.). The mover of No.3 Resolution on the 2nd Platform was Symes.

Also In May, Fleming took his unemployed agitation to the point of rushing onto Melbourne's Prince's Bridge to halt the Governor General's (Lord Hopetoun) carriage which was crossing through 'cheering crowds' on his way to open the first Federal Parliament. Hopetoun told the police not to interfere and listened to Fleming put the case for the unemployed.40 Later, on the evening of 'the big spread' (the Exhibition Banquet), Fleming represented the unemployed again by strolling into the hall, had "a friendly confab with one or two Labor members who greatly enjoyed the idea, (then) proceeded to luxuriate in the toffiest part of the whole assemblage. His presence was a grief of mind to Detective Macnamany who assiduously tailed him up for 3 hours and a half. At the end of that time Fleming got tired of the sport and considerately gave the officer an opportunity of showing him the door ... "41

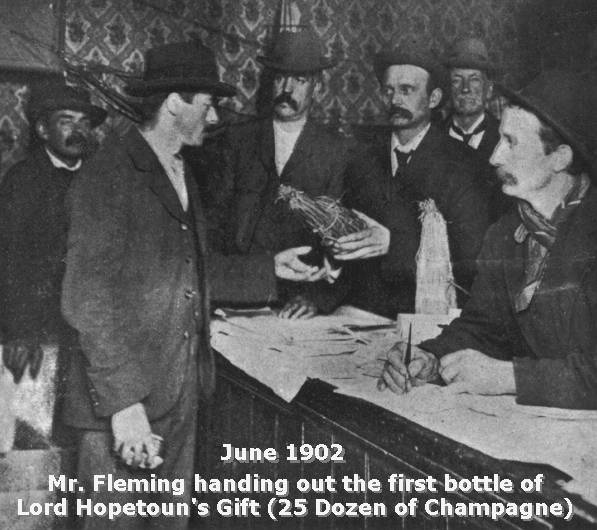

The departing Governor-General later 'entrusted' J.W.F. with the distribution of gifts of food and champagne to the unemployed. Lord Hopetoun had apparently been told by G.M. Prendergast that Chummy was 'the most honest man I know' and that he had an unofficial directory of unemployed. There is, again, some uncertainty about details for this story, as George Blaikie says the gifts came from the Governor-General as a kind of round-about slap at the establishment for refusing to pay Hopetoun what he thought he needed.

In any event 1/- was given to each married man who attended distribution day, June 24, 1902, outside Fleming's shop, and 6d to each single man. The next day 300 bottles of champagne augmented by 6 hogsheads of 'Fighting Beer' from Shamrock Brewery were distributed. Though it went smoothly for a while, the distribution of the booze became a riot, according to some. Fleming, who neither smoked or drank lost some days in the task but took none of the money for himself either.42 On a more practical level, Hopetoun is credited with pressuring the government to speed up government work projects. Out of the original encounter came a friendship which endured after Hopetoun returned to England. While still in Australia, he is said to have visited Chummy's house, which was built with money he loaned to Chummy, the house bearing the name 'Hopetoun' when completed.43

A representative of "The Age" asked Mr Fleming why the wine had not been sold and the money distributed. His reply was perhaps characteristic. He said: "We are tired of the inequalities amoung the people. The rich drink champagne and the poor small beer. Besides, it would have been a breach of faith to his Lordship to have sold the wine". When "The Age" reporter pointed to the drunken mob outside, and asked if that was the equality he meant, Mr Fleming could only say that such a thing as the distribution of champagne had never occurred before in Australia, and that champagne was not intended only for dainty stomachs. On Tuesday Mr Fleming was the secretary of the unemployed. Yesterday he was seeking by beer and champagne to create the effervescent equality of the Socialist. The Age, June 26, 1902

|

In 1901, another attempt had been made to stifle 'the Bank' speakers and it's clear that by this time Fleming on his Freedom platform was already an institution. He conducted the meetings on the Yarra Bank,44 and continued his work there, on what was virtually a private stand until his death. Fleming and White also kept the Free Discussion Society going, Fleming using this venue to speak on the Paris Commune in March, 1902.45 A letter from him to Tocsin, 26 September 1901 says that the T.H.C. flag "is at half-mast for President McKinley's death, why? and why not on all occasions when workers are shot down, etc?" In November, he moved a motion that the T.H.C. "protest against the reduction of old age pension from 10/- to 8/-". Fleming wondered why people had not risen against the move, and attacked Trenwith and others. Pewen in 'Randomania' mentioned that Fleming's motion at T.H.C. to debar trades unionists from becoming professional soldiers lapsed, and comments that it should have been passed unanimously.

It would seem that after a long period of working with trade union and shall we say 'legitimate' channels, his uncompromising anarchism reasserted Itself. The 'Peoples Daily' (of 1904) records 'Anarchy, Its Teaching and Objects' by him which begins a series of exchanges through the paper resulting In his being expelled from the T.H.C. for attacks on Labor parliamentarians'46 (disloyalty to Labor). He spoke in support of communist anarchism at this time47 and of dynamite 'overcoming dual opposition of police and military'48 On 'the Bank', according to the Daily Telegraph he referred to Labor Parliamentarians including Dr. Maloney, as tyrants, said people should seize Parliament House, burn title deeds to property and erect an anarchist community. He also spoke of an attempt to raise funds to tour Victoria and to rent a room as his headquarters in the city.49

On his being expelled, Fleming 'demanded a hearing ... then became heroic':

'... I am going to be expelled because I am an anarchist. I am in the company of Tolstoy, Spencer and the most advanced thinkers of the world. Workers will never get their rights while they look to Parliament. A general strike would be more effective than all the Parliaments in the world. I have got a fine stick and I am going to use It. Expel me if you like. I am an anarchist. We have been hanged in Chicago, electrocuted in New York, guillotined in Paris and strangled in Italy, and I will go with my comrades. I am opposed to your Government and to your authority. Down with them. Do your worst. Long live Anarchy'.

Other private publications included a Manifesto and a response to a letter from Kropotkin which itself is a result of Fleming's continuing contact with the international anarchist movement. As 'Anarchist Leaflet No.31 Fleming published Kropotkin's letter which he claimed had been suppressed by the T.H.C. The pamphlet reads in full:50

'Comrades,This is probably 1905.

The following letter was suppressed by Messrs. Barker and Scott and the executive of the Council. In fairness to Mr. Dobson, one of the executive, I wish to state he expressed surprise, as he heard no mention of the letter at the Executive Meeting, although Mr. Scott had one, two weeks before the meeting and Barker several days.Barker informed the Council that the Executive did not think it wise to read it to them. While the Barkers and Scotts are scheming after fat Parliamentary jobs, with six or eight pounds a week income to while away the time on soft cushions seats, the misery of the workers is almost beyond endurance. Workers awake! Free yourself from Political Shysters. Don't vote! Declare for the General Strike. 'The Political Labor Party's dead slow'- Tom Mann.

Etable, France.Viola,

Bromely, Kent.

Dear Comrade,

Thank you very much for your letter. Things must be worse than I thought, if the labor organisations are entirely in the hands of politicians. I have still the hope that apart from those workingmen who lay their hopes into Parliament there are men who will understand that the progress of Labor Unions is not politics, but what in Latin countries is described by the working men as Direct Action.Do you follow the movement in France? The Syndical (Trades Union) movement which for a number of years was in the hands of political socialists, is now freeing these bonds, and we see really a new birth of what was the International Workingmen's Association before the Franco-German war; their aim is the Direct Action against Capital and Philistine Rule. Even when they want to obtain something from Parliament they think - quite right - that it would be better to impose their will, by strikes etc, instead of begging. They prepare, as you know, the General Strike for May 1, 1906. What are you doing in Australia for this eventuality? It is time to think of it. I would be so happy to go to Australia and to help the Labor Movement in any way. But since I have had an attack of the heart I have had to give up all lecturing. Are you receiving regularly 'Freedom'? There is a general revival of the movement in Europe.

I am for a few weeks in France but return to Bromley about 10th of Septernber.'

With best brotherly greetings, P.Kropotkin.

Tom Mann, as Chummy's reference above shows, was another agitator with international connections who was less than impressed with Australia. The snide piece, 'Anarchists at Home' reported a meeting held by Fleming, White and Mann with 200 or so others, but which T.H.C. speakers decided to boycott. Apparently an election was due:

'Comrade Mann girded a good deal at his masters of the Trades Hall. He dared them to make a martyr of him for worshipping openly instead of secretly at the sacred shrine of anarchy... Tom passionately embraced the red flag of anarchy which hung limp on the breezeless platform ... '51

In 1908, continuing the work, 'Chummy' and Percy Laidler, a Marxist, led the unemployed into Federal Parliament, stopping it for one and a half hours.52

In 1907, according to her autobiography, 'Living My Life', Chummy had invited Emma Goldman to tour Australia and had raised money for her fare. She says that at the time she could not have faced the long journey alone, but 12 months later, deeply involved with Ben Reitman, she made preparations to go.

'Ben was wild with the idea of Australia; he could talk of nothing else and was eager to start at once. But there were many arrangements to make before I could go on a two-years tour'.

Their departure for the 'new land' was set for January, 1909, and 1500 pounds of literature was despatched. A struggle for free-speech in San Francisco forced a postponement, and in the Melbourne 'Socialist' In April, 'Chummy' announced that Emma had left Vancouver on the 'Makura' on 26 March for Australia. But she had not embarked.

A report In the London-based 'Freedom' for May 1909 emphasises the cost of travel as the impediment to an Australian tour at that time, yet also refers to 'an ominous report that the police are striving to hunt her altogether out of the States.'

In fact, she had received a telegram at the last minute which, she claimed in her memoirs, meant allowing the Government to alter her plans and make her a virtual prisoner In the United States until those same authorities decided to deport her to Russia ten years later. From an abandoned marriage of years before she had gained what she thought was US citizenship but the Immigration Department had revoked her husband's papers on a technicality in order to declare her an alien. Thus if she had left the country she may not have been permitted to return. Not wishing to take the risk of becoming a stateless person she says she cancelled the trip.

'It was a bitter disappointment much mitigated fortunately, by the undaunted optimism of my hobo manager. (Reitman)'

The question here of Reitman's part in Emma's decision is an intriguing one. Recently, Candace Falk, now director of a mammoth attempt to document Emma's life, found a cache of love letters between the two in a music-store trunk in California. Falk found, in the letters, how, at the time the Australian tour was being arranged, she and Reitman were at odds over his promiscuity and her apparent inability to cast him aside or to get him into context.

'Although Emma's espousal of the ideal of free love kept her from condemning his behaviour on political grounds, her letters revealed a tortured effort to reconcile her bitter disappointment and anger with her ideology ... Australia seemed to promise an escape from the forces sapping her spirit, and by considering going without Ben, she acknowledged that he was one of those forces'.

Falk quotes from one of Emma's letters to Reitman as she struggled with the need to continue her public efforts and persona, while racked with a deep pessimism that threatened her life's work:

'Life Is a hideous nightmare, yet we drag it on and on and find a thousand excuses for it ... I am strongly contemplating giving up everything ... and going to Australia, travelling a few years alone. 1 can get the money tomorrow, this minute, if I can only pull up strength and go. I want to do it, as I see in that the salvation out of my madness'.

Falk concludes that It was Emma's indecisiveness and submission to Reitman's 'power to determine her emotional stability' that kept her in the United States.

On the other side of the world and well away from any knowledge of the emotional interplay, yet obviously still in contact by cable and letter 'Chummy' continued to believe that a trip was possible. In a letter to her of 16 December 1909, he wrote,

'With regard to your visit I am doing all I can'.

She clearly did not contradict him for in 'Mother Earth', the magazine she edited in the US, nearly twelve months later, she quoted from another of his letters:

'Comrades in Sydney and Adelaide are anxious for you to come, and are organising into committees to raise funds and arrange meetings. You can look forward to a successful tour'.

In Melbourne, the baby of two unmarried members of a local anarchist group was named Goldman by 'Chummy' at his speaking platform on the Yarra Bank. Towards the close of the ceremony, Catholic rowdies rushed the platform throwing stones, howling 'like hyenas' and attempting, as they had before, to destroy this venue for divergent opinions. In his 70's, nearly 30 years later 'Chummy' was still being roughed up by the same sorts of people.

He could not have known that at about the time he was christening the baby, Reitman was heading into probably the most traumatic experience of his life, and one which probably ended any chance there was of Emma leaving him for Australia. In 'Living My Life' she describes how, nearly three years after the free-speech fight that caused the Australian-tour postponement in 1909, her lecture tour brought her back to the same area, in particular to San Diego. There, at the height of another burst of anti-radical hysteria, a group of Vigilantes abducted Reitman at gun-point, stripped and beat him, burnt the letters 'IWW' into his skin, tarred him and comprehensively humiliated him. It will be some time, perhaps never, before history can make conclusions about the consequences of such an experience on the emotional state of the two, and on, for example, their willingness to leave the United States.

But how might Australian society have dealt with the phenomenon of Emma Goldman in its midst, urging birth-control and free love, opposing conscription and joining forces with the antipodean scourge of religious bigotry and labor opportunism? Would Australia have been a means to refresh her spirit, would it have proved equally as brutal, or would she have quietly slipped into a far less controversial and far more private role, seeking as she said in 1909, to give up everything?

Also in 1909, Fleming had continued active on behalf of Harry Holland jailed during an industrial struggle in Broken Hill, through the Release League. Meetings continued each month, collecting money for Mrs. Holland and children until Holland's 2 year penal sentence was reduced and he was released in October.53

He was active in the anti-conscription struggle during the first World War, being with the IWW prepared to take definite attitudes. In Port Melbourne Town Hall for example, he spoke on 'the Rich Man's War and the Poor Man's Fight'. During this period he was frequently arrested, jailed and threatened with being deported by the authorities, or thrown into the river by roughs and on at least one occasion was thrown in, being saved by Laidler.54 He formed some connection with the Paris-based Groupes D'Etudes Scientifique which brought together, as the Australian Anarchist Group, a network of otherwise isolated activists and anarchist sympathisers in Sydney and Melbourne during what was a very low point for anarchism.55

I haven't yet been through all the newspapers or possibilities56 sources of letters for the period 1900 to 1950 when JWF died, and there is much yet to be found out about this man.

'As he became older he felt he had a proprietary claim on the day (May Day) and insisted on leading it with his flag (red, 'anarchy' in white diagonally across it). The May Day march and celebration was revived after some years in 1924, and JW, after Percy Laidler unsuccessfully tried to talk him out of leading it, walked about half a block ahead.'57

Ron Testro wrote later:

'Counter demonstrations were often staged by the Irish and on one occasion one Irish bandsman hit Chummy over the head with a trombone. Fleming counter attacked by renting the Hibernian Hall for his Anarchist meetings. The Hall at this time was privately owned'.58In the thirties when the Communist Party was the main factor in organising the May Day it did not welcome 'Chummy' and his flag leading it. So, he started a block ahead, going so slowly the march caught up with him, or sometimes he started back In the ranks and gradually edged to the front. In 1933, he was invited to make what may have been his last public speech, apart from those on the Yarra Bank. The C.P. Congress Against War and Fascism asked him to address the delegates. Characteristically he provoked criticism by, among other things, taking the organisers to task for their doctrinaire approach.

There is also heresay evidence that he continued talking to university students up to the 1939-45 War and to have formed an Anarchist group. In a 1933 letter to Nettlau he claimed to have celebrated the memory of the Haymarket anarchists 'every year' since their assassination in 1887.59

Smith and Bertha Walker both record the sadness of the almost alone J.W.F. getting older but continuing to do what he could, in particular maintaining his pitch on 'the Bank'.

Smith and Bertha Walker both record the sadness of the almost alone J.W.F. getting older but continuing to do what he could, in particular maintaining his pitch on 'the Bank'.

'... Every Sunday until his death... he took his stand under a tree at the Yarra Bank and summoned a few cronies with a tattered cow-bell. Draped on the branches of the tree above were two faded red flags with 'Anarchy' and 'Freedom' worked on white. The little man with his trousers rolled at the cuffs would preach in a quavering voice at the inequities of government and religion. With his milky eyes fixed beyond his listeners he would tell of the coming reign of earthly happiness and brotherly love.'60

He died at home aged 86, on 25/26 January 1950, in somewhat squalid conditions: '... none of his personal effects were of any value whatsoever'. 'Recorder, 1962' shows Jim Coull and Percy Laidler as executors of Fleming's will, his cottage and money going to two English relatives and a Professor Joad, while his papers were taken by police.61

'On the eve of May Day after (his death) it was suddenly recalled that Fleming had asked that his ashes be scattered on the Yarra Bank on May Day. They did not have the ashes. Said Laidler quizzically 'Does It matter what ashes they are?' A member of the Butchers' Union took the hint and came along with a large biscuit tin full. (Laidler) got up and made a speech about Fleming, punctuating it with the throwing out of handfuls of ashes which blew in the Melbourne wind all over the crowd'.62 '...to the very end respected and esteemed by the radical elements in the labor movement because he was sincere, courageous, indefatigable... Bernard O'Dowd was not the only man who learned something from him. Percy Laidler ... told me that a number of men prominent in the labor movement had learned from 'Chummy' Fleming'.63

1. Merrifield Notes, La Trobe Library, source perhaps 'Tocsin' 17 October, 1901. Death Certificate says he was 86 in 1950.

2. Tocsin, 17 October, 1901.

3. Liberator, 1885, p. 553.

4. Liberator, pp. 777,789,871.

5. Liberator, 17 July, 1887, 6 November 1887 (p.401.), 20 November 1887 (P.440).

6. Honesty, February, 1889, p.5.

7. Richmond Courier, June 29 1889, quoted in Australian Radical, 13 July, 1389, P.l.

8. B.James, 'Anarchism and Political Violence in Sydney and Melbourne, 1886-18961 MA, La Trobe Uni, 1984.

9. Recorder newsletter (Melb) Vol 1,No.5 and No.60.

10. Australian Workman, 6 June 1891, p.2.

11. Commonweal January 18,1890; Liberator, February 8 and 22, March 8 and 29,1890.

12. F.Smith, 'Free Thought and Religion in Victoria, 1870-18901 MA, Melb. U, p.257;

13. Liberator, 17 October, 1886.

14. AG Stephens, 'Autobiographies of Australian and New Zealand Authors and Artists' unpublished Ms. in Mitchell Library.

15. VOBU records begin 7 September, 1885, at Labor Archives, ANU.

16. Recorder newsletter; also K.Kenafick, unpub. Ms on Blackburn

and Curtin, ANL, pp.909+.

17. 'Age report in J.Harris, 'The Bitter Fight' p.61.

18. 'Labor's Pioneering Days' p.136+. This is mainly about New Zealand.

19. L.Churchward, 'The American Influence on the Australian Labor Movement', Historical Studies, Vol.5, p.264,fn.

20. Commonweal and Workers Advocate, 15 April and 21 April, 1893.

21. Australian Radical, June 1,1889.

22. Socialist, July 6,1907;VOBU records, 'Hummer'' 7 May 1892; Colin Williams 'Brief History of May Day Celebrations'.

23. 'Beacon' journal of the Single Tax Movement, Henry George League, Melb.

24. 'Progress' newsletter for Land Nationalisation Society and Free Trade Democratic Association, VSL.

25. See also Honesty, August 1888,p.98.

26. See James as above.

27. 'Hummer' 16 April 1892, 'Truth' 10 April 1892, and Andrews in 'Tocsin' 17 October 1901.

28. 'Melbourne Herald', 28 July 1892. 'Hummer" 18 June 1892, 2 July 1892; Brisbane 'Worker' 16 July 1892, p.4 Melbourne Herald 1 August 1892.

29. VOBU minutes 17 June 1895.

30. 'Beacon' October, 1895 also.

31. 'Champion' 14 December 1895 p.206.

32. 'Tocsin' 27 April 1899.

33. 'Tocsin' 8 June, 22 March, 13 July 1899.

34. 'Tocsin' 14 September 1899; 21 September 1899; 23 November 1899.

35. 'Tocsin' 14 December 1899.

36. 'Tocsin' 8 February 1900; 7 December 1899.

37. 'Tocsin' 8 June 1899.

38. 'Tocsi n' 10 January 1901.

39. 'Tocsin' 18 April 1901.

40. 'Tocsin' 9 May 1901.

41. 'Tocsin' 16 May 1901.

42. 'Age' 25, 26 June 1902.

43. 'The Australian Commonwealth' B.Fitzpatrick, p.p. 92,93.

44. 'Tocsin' 26 September 1901.

45. 'Tocsin' 13 March 1902.

46. 'Peoples Voice' 9 April 1904, 'Daily Telegraph' 4 April 1904, 14 April 1904.

47. 'People's Daily' 25 February 1904.

48. 'Daily Telegraph' 4 April 1904.

49. 'Daily Telegraph' 9 April 1904.

50. Dwyer Collection, Mitchell Library, ML Q335.8,

51. Port Fairy Gazette, 24 November, 1903; see also Avrich in 'Freedom' 23 July 1977.

52. 'Solidarity Forever' p.13, pp 62-65.

53. 'Solidarity Forever', p.88.

54. See Labor Call, July 8,1915,p8; Argus, 14 July, 1915 and Alf Wilson's Memoirs, p.4., p.p. 93-94, Melb. Uni. Archives.

55. GES pamphlet, 'What Is Anarchism (etc)', Sydney,1912;

56. See Argus Index e.g. 1915-16.

57. 'Solidarity Forever' p.236.

58. Argus, 8 December, 1945, see also Melb. Herald, 7 July, 1947.

59. Fleming to Nettlau, 3 September, 1933, IISH, Amsterdam.

60. F.B.Smith thesis, p287. 1953 is given, erroneously, as the death date.

61. Executor of Estate in letter to Merrifield 26 March 1962.

62. 'Solidarity Forever' p.271.

63. Kenafick, p.465.

From 'Anarchism in Australia: An Anthology 1886-1986' ....edited by Bob James

Also of interest: