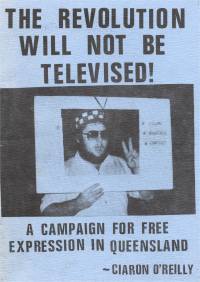

Pamphlet Cover

Pamphlet Cover

|

The successful Free Speech campaign in Brisbane during 1982 and 1983 is well documented in this pamphlet by Ciaron O'Reilly. Since the late 1960's Brisbane has had an active and diverse number of anarchist and libertarian groups, which have been prominent in all protest movements and local campaigns.

|

The nonviolent struggle for free expression in the Brisbane Mall is located in two contexts. In terms of the aspirations of those anarchists and radical christians who participated in the "Committee of 50" and "People for Free Expression", the struggle for free speech is a basic tenet to the revolutionary society they are attempting to create. These groups worked effectively together because of the high agreement they shared in terms of what they were working for and how they were going to work for their objectives. The campaign is also located in the 16-year struggle for the right to express oneself in Queensland society. The previous struggles for civil liberties, beginning in 1967, have involved thousands of Queenslanders from different perspectives, for example, aboriginals, ecologists, marxists, anarchists, christians, socialists, social democrats, feminists and liberal democrats.

Although these campaigns achieved unity in what they were struggling against - embodied in the slogan "JOH MUST GO" - they failed to achieve a unity in what they were struggling for in terms of human freedom. Indeed, roughly four different positions emerged in relation to the right to march; there were those liberal-democrats who supported the permit system but were disturbed by the 1977 right of appeal being taken from the magistrate's court and placed in the hands of the police department; the social-democrats who wanted a change to the South Australian system of 3 day notification where the onus is placed on the police to prove in a magistrates court why a march or demonstration should not go ahead; there was the authoritarian left who scoffed at the "bourgeois concept" of civil liberties for all and demanded the right of the working class and its representatives (themselves) to expression and the right to suppress the expression of the "enemies of the working class" (this included attempts to smash the Right to Life March and the overturning of a National Front information stall); and the libertarian position defending everyone's right to free expression, even those people with whom they disagreed.

What made the Mall Campaign distinctive from the outset was that it was solely within the parameters of the libertarian position that both the "Committee of 50" and "People for Free Expression" were formed and that we were now in open resistance to A.L.P. City Council Ordinances, the vigilante repression of the authoritarian left as well as the National-Liberal Party State Government Traffic Act regulations.

The Commonwealth Games Act (1982), with its threats of severe punishment and its purpose to silence Aboriginal dissent during the period of the Games, was a catalyst for libertarians to take up the issue of free expression. The view of those participating was that the only cheap accessible means of communication available to ordinary people was being denied in Queensland by the police permit system under the Traffic Act, the municipal permit system under the City Council Mall Ordinances, and the occasional State of Emergency legislation like the Commonwealth Games Act. The "Committee of 50" was formed to carry out a day of action on September 15th (1982) when it would declare a "Free Speech Mall" and "Freedom of the City" and would openly break the permit systems as a way of encouraging community non-cooperation.

The Committee embodied a wealth of experience containing libertarians who had been involved in direct action in the 1967-69 Civil Liberties movement, the 1971 Springbok Tour and the 1977-79 Right to March campaign. The group shared the following analysis of the past 16 year struggle for free expression in Queensland.

"THE PERMIT SYSTEM THE ESSENCE OF THE PROBLEM"We have chosen to disobey the Traffic Act and we are demonstrating before the Commonwealth Games Act comes into force to make it clear that the denial of the right to free expression is nothing new in Queensland. This denial has been secured by the permit system under the Traffic Act, including the 'catch all' section of 'disobeying a lawful direction'. Through selective bans (refusal to grant permits) on street marches (and a total ban on political marches from 1977-79), leafleting, public street speaking and assembly, the government has been able to suppress discussion within the community about a number of issues which it finds threatening. Discussion has been limited by selective bans or by direct police intervention.

It was the persistent occurrence of this problem for the Anti-Vietnam, anti-conscription movement in the early sixties that led to the civil liberties struggle of 1967-69. It was this campaign (with 4,000 people marching and hundreds of arrests in 1967) which resulted in the loosening of the permit system with recognition of the right of appeal to magistrates against police decisions (and the dropping of such officious rubbish as $2.00 fee and a permit for every placard). It was the dropping of the right of appeal and the threat to refuse all permit requests which constituted the change Petersen made in 1977.

Some vital issues which have been limited in their public airing by the permit system have been Australian racism and South African sporting tours (against which a State of Emergency was also declared), banning of SEMP and MACOS, nuclear power and uranium, the role of multinationals in Queensland and in Asia, land rights and nuclear war.

Neither magistrates (the old system) nor police (the system since 1977) should control political expression on important matters such as these. If we accept this than we accept that the only legitimate political activity is what goes on in parliament (and what goes on in there is often distinctly illegitimate). If we agree to that then we are declaring ourselves powerless. The civil liberties movement of 1977-79 demanded an end to the permit system. Many groups, even those sure of a permit, refused to beg for what should have been their right. There was growing dissension amongst police about having to enforce these laws.

Eventually people began applying for permits. In August 1977 the Government, because of the pressure applied by the movement, began granting some permits (beginning with a Nagasaki march). The blanket ban ended and a selective ban (without appeal) took its place. But the movement was back to square one - demonstrating when the Government wanted to allow demonstrations, but not expressing itself when the Government did not want demonstrations (for example refusing a permit for this year's Hiroshima Day march). So at best the results of 1977-79 could be called a compromise. In essence it was a defeat. The march ban is still in general effect. Marches which get permits are usually at ineffective times when no people are about. The principles of the permit for "free" expression is largely unchallenged. There is no clarity of opposition to it.

There are many issues about which the individuals in the Committee of 50 wish to express ideas and take action. We do not want to have to confront the police every time we do so. Nor do we wish to forego these issues in order to fight constantly on the civil liberties question. But we do not wish to remain circumscribed in our ability to communicate with people. The means of communication denied us by the Traffic Act and by the supplementary ordinances of the Labor Party in the Brisbane City Council are the only reliable channels under our control. The mass media are in the hands of the rich and powerful. The mass media operate in a way which makes it impossible to communicate anything but the most simplistic notions.

Many people have found that it is possible to circumvent the Traffic Act; to not apply for permits and still communicate effectively while avoiding confrontation. We certainly do not want to revive the civil liberties movement in the form it eventually took - as if the only avenue for action was to repeatedly try to march from the City Square (marxistlemmingism). Father we would seek to revive those imaginative and colourful forms of action such as guerrilla marches, decentralised actions, theatricality as well as the whole range of traditional activities such as pickets, vigils, street-speaking which many people have been successfully using to circumvent the Traffic Act.

We do accept however that it will be necessary to risk confrontation from time to time while pursuing various issues. It is also necessary to draw attention to civil liberties itself (and censorship etc.) as an issue as long as this does not take over from the development of campaigns on other matters. It would be good if dissidents in Queensland displayed a clear commitment to the demand for the democratic right of free expression for everyone no matter what their opinion (many on the left support a permit system and censorship, being only in disagreement with the way it is operated now). It would be good if non-cooperation with the permit system could arise as the result of such a belief (1)".

The Committee called for the following

Finally we call upon all people (and the Brisbane City Council) to establish the Mall as an area for free speech as a step on the way towards generalising freedom of expression (2)".

- The end of the permit system:

- No permits to be required for leafleting, public street speaking, busking, picketing, assembling in public parks, or carrying placards (of any size). (There is no real question of obstruction or serious inconvenience for anyone in any of this).

- No permit system for marches.

- The repeal of the "Commonwealth Games Act".

- We call upon the Queensland Labor Party to repeal its oppressive municipal ordinances.

- We call on:

- All those people in the community who remain committed to democracy to refuse to cooperate with the permit system by refusing to apply for police permits.

- Those members of the Queensland Police Fore who remain committed to democracy not to enforce the permit system by refusing to take action against leafleters, marchers, buskers, picketers, mimics or any other people expressing their democratic rights of free expression (a letter to this effect is being circulated to the police).

- All people to boycott the Commonwealth Games to protest the denial of aboriginal land rights (expressed most recently in the Land Amendment Act passed in April) and to protest the denial of civil liberties in Queensland including the Commonwealth Games Act.

To avoid as what it saw to be the pitfalls of previous civil liberties campaigns the Committee committed itself to the operational principles of direct action, civil disobedience, non-violence, direct democracy, and open platforms.

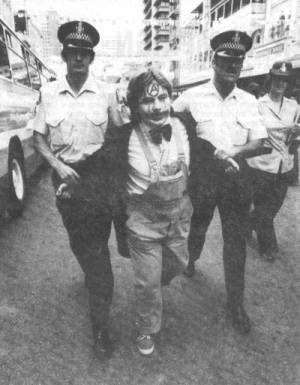

The nature of the "Committee of 50" day of action (Sept. 15th. '83) was one of 'propaganda of the deed' - with a theatrical opening of the "Free Speech Mall complete with ribbon cutting and a top-hatted robed Mayor who introduced the civil disobedience in verse. The leafleters, buskers, speakers, actors, picketers were all introduced with a systematic tearing up of application forms for permits. The message was clear - end the permit system: exercise free expression. The City Council ordinances were not enforced, although $25 on-the-spot fines had been threatened earlier that week by then Acting Lord Mayor Len Ardill. These fines were also threatened later in the campaign but never enforced, a sub-goal had been realised on the first day of action. Another ribbon was cut and "Freedom of the City" was declared. The Committee took the civil disobedience outside the Mall in defiance of those authoritarian regulations existing under the Traffic Act. Humour was an important ingredient of the campaign from the outset, both for the value of communicating ideas to the public and enriching the morale of the activists involved. Posters proclaiming "Bill Posters is Innocent" appeared around the city next to the official injunction proclaiming "Bill Posters will be Prosecuted", some "Committee of 50" activists dressed as clowns, while the banner leading the finale march proclaimed "PERMIT SCHMERMIT". To the tune of "Ten Green Bottles" the marchers sang "Ten smiling marchers marching down the street, ten smiling marchers marching down the street. If a Queensland cop one should accidentally meet, there'd be nine smiling marchers marching down the street etc.". As the marchers were being arrested and placed in police vans a recently arrived busker spontaneously joined in playing "The Last Post" on his trumpet. He too was arrested after complying with a police direction to put his trumpet away but insisting on his right to remain with other onlookers on the sidewalk. Twenty-two people were arrested.

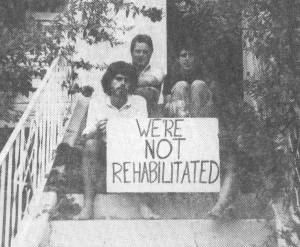

The emphasis on non-violent creativity and humour stands in contrast with the macho militancy of many previous civil liberties campaigns. Its effectiveness was reflected in the response of the public as reported in 'The Courier Mail' the following day (16/9/83)" the marchers moved into the street to the cheers of a large crowd which had gathered on the footpath (1)" and in its contribution to sustaining a demanding weekly campaign over twelve months involving a relatively small number of libertarian activists. An important element to the campaign which was evident on the first day was the sense of community amongst activists. Half of those arrested had come from three West End based communes. This high level of affinity contributed much to the stamina, quick response mutual aid and personal support evident throughout the campaign. Believing that the only way to make these laws unworkable was through mass non-violent non-cooperation, four of the radical christians decided to extend and deepen their non-cooperation by refusing to pay fines imposed by the magistrates court. This took resistance to its logical conclusion and moved the 'financial punishment' from the dissident to the state, which had to keep resisters in prison at a cost of over $500 a week.

|

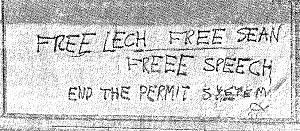

During Sean's imprisonment libertarian activists returned to the Mall in a solidarity action with both Sean and the Polish Solidarity movement (who were involved in a Day of National Action for free speech). Libertarians distributed an illegal leaflet containing an "Open Letter to Russ Hinze", Minister for Local Government, pointing out his connection with the Moscow Narodny Bank and their suppression of free speech in both Queensland and Poland. Christians and anarchists spoke and leafleted in defiance of the Council Ordinances and warnings from Council officers threatening $25 on-the-spot fines. 'The theme of the speeches was ' relationships and similarities between the suppression of free expression in Poland and Queensland'. The retreat of the council officers in this demonstration signalled a decisive victory for the movement and offered pragmatic reasons for a concerted escalation of open disobedience as a means of liberating the mall.

During the January ('83) jailing of Ciaron O'Reilly libertarians took part in a guerrilla street march from the City Square to the Mall and held a demonstration consisting of (illegal buskers), speakers and leafleters. The following Friday people returned to the Mall. These soapbox speak-ins were the first of a weekly campaign that ran for 10 months.

The following day (Sat. 15/1/83) illegal street speaking was held in West End. This was, followed by a march on West End police station where a number of police reinforcements and Special Branch had gathered. On arriving at the police station John Nobody and Jim Dowling demanded that police tear up their warrants they had for their arrest as a commitment to free expression. The police declined the invitation placing them both under arrest for failure to pay their fines. They also arrested three others as they cleared the crowd that had gathered. John and Jim began their two week imprisonment, daily vigils outside the prison and Friday night speaking were resumed. It was in this period that libertarians decided that the Mall was "winnable" through a concerted campaign. Resistance to the broader restrictions of the Traffic Act, however, would have to be restricted to spontaneous guerrilla activity. Following several Friday nights of soap-box speaking it became obvious that this was a medium worth fighting for - a way of realising spontaneity, two-way communication, and in itself an act of resistance to the passive consumerism of the Mall and hence beneficial to the myriad of campaigns libertarian activists were involved in. With this realisation the "People for Free Expression" was formed.

To both the anarchists and radical christians who formed the "People for Free Expression" the basis of social change is the spreading of revolutionary ideas and the living out of those new ideas in the shell of the old social order. This stands in contrast with the authoritarian left who use the civil liberties struggle to accentuate class struggle by getting workers onto the streets in confrontation with the forces of the bourgeois state, and the A.L.P. who take up such struggles to score political points over their parliamentary rivals. This desire of anarchists and radical christians to spread ideas made street-speaking a more desirable medium to defend than the right to march past the masses and chant at them. It was this concept of social change and its emphasis on ideas that saw street speaking as a political activity in itself, not merely as a means to headline hunting ends or as a way to engender street confrontation. It was revolutionary to go to the Mall to speak and to be spoken to politically, to encourage people to shrug off their passivity. If confrontation with the State was to occur, the desired aim was to make the contrast clear (who were the democrats, who were the oppressors) and, through non-violent unannounced guerrilla activity, make the law unenforceable.

|

In the Mall, with the people, the medium was the message, the action was the aspiration, we embodied the reality we desired as we went weekly to the Mall. Not only to speak about the right to speak, but also about a myriad of issues. For libertarian activists the struggle for the Mall coincided with other struggles they were involved in; speeches, theatre and busking took up questions of the Franklin Dam, nuclear weapons and the movements against them in East and West, prisons (particularly the local Boggo Rd. jail), East Timor, Central America, anarchism vs marxism, radical christianity, Aboriginal rights, the conservation of rainforests, sexism, the 1983 elections, fascism, Russian and United States imperialism, the National Economic Summit, the purpose of the Mall and civil liberties here and elsewhere. Some issues were lived out in the campaign - passive consumerism, secret police, Ghandi. For the people who listened, their curiosity was revolutionary; to stand and listen was to participate in an "unlawful assembly". Many passers-by took the soapbox; many defended our right to be there when we came under attack from the police.

The formation of "People for Free Expression was an attempt to involve people outside of the immediate anarchist community. The statement of demands and method was a rehash of the "Committee of 50" statement. There was limited success in involving others in an activist role. Success did occur through the weekly "Open Forum" at Queensland University which was created by campus-based members of the P.F.E. There was also a significant success in the new year mobilising other anarchists and radical christians.

Increasing numbers of activists were beginning to master the art of speaking publicly, the response from passers-by was generally positive and the only resistance in the first six weeks of regular speak-ins was in the form of the personal crusade unleashed by the "Mall Manager' (a representative of the City Heart Business Association). He would hurl abuse, turn up the piped muzac to attempt to drown us out and occasionally attempt to provoke incidents of violence - this included involvement of the police who legally had no power. At the beginning of March there was a general feeling amongst libertarians that we had won a quick victory. We were going to concretise our real gains by continuing to speak in the Mall on Friday nights and to collect signatures for a list of demands "petitioning the Australian Labor Party (Queensland Branch) to advise the A.L.P. controlled Brisbane City Council that it should repeal all the Queen St. Mall Ordinances which deny the rights to various forms of free expression (2)".

On March 24th the A.L.P. Mayor, Roy Harvey, and the National Party Local Government Minister, Russ Hinze, foreshadowed State legislation which would give police power (similar in effect to the Traffic Act) to arrest people for exercising expression without permits in the Mall. As Mr. Hinze (National Party) introduced the amendments into State Parliament he stated in "The Courier Mail',

"Representations have been made by the Lord Mayor, Ald. Harvey (A.L.P.) and by business houses operating in the Mall concerning problems being experienced (3)".

The "Daily Sun" reported,

"Plans to empower police to stop demonstrations (sic) in the Queen St. Mall would not infringe civil liberties, the Lord Mayor, Ald. Harvey claimed yesterday.Ald. Harvey said the proposed legislation returned to the police controls they exercised in other publicly owned parts of the city.

Those powers had been inadvertently removed under a section of the Queen St. Mall Act which was written with the intention of preventing police from permitting demonstrations.

But removal of permit powers had accidentally removed police power to prevent demonstrations.

Ald. Harvey claimed the council had received complaints about illegal busking, pamphleteering, charity collection and demonstrating by people who had refused to obey council laws.

He said people had avoided fines of up to $500 by refusing to give their names, and the council had been unable to ask for police help (4)".

The "Australian" reported

"In a statement telexed from Mr. Hinze's office, a spokesman for the (City Heart Business) Association, Mr. Graham Campbell-Ryder had asked Mr. Hinze to provide a greater protection for shoppers 'from political activists and others who attempted to harass Friday night crowds'.He said the Association had auditioned buskers to entertain shoppers. It did not regard "longhaired, barefooted guitar-carriers as buskers: They are not buskers, but they are beggars" Mr. Campbell-Ryder said (5)".

The conspiracy was obvious. The lawmakers were comprised of three distinct groups; the City Heart Business Association, the A.L.P. City Council and the National-Liberal State Government. At the beginning of the campaign, the A.L.P. Council had full jurisdiction over the Mall and $25 on-the-spot fines. The National-Liberal State Government had a track record of 4,000 political arrests under the Traffic Act but no legal muscle in the Mall to silence dissidents.

The City Heart Business Association saw the mall as an extension of their shop fronts. A place to promote their products and guarantee a consumer culture with piped muzac, 'bikini girls', fashion parades, car raffles and a handful of sanctioned buskers. What P.F.E. hoped to achieve was to at least split the consensus amongst the shop-owners marshalled by Mall Manager Campbell-Ryder in opposition to free expression. We wished to allay real fears that we may want to dominate other people's activity in the Mall. This was done by stating our position in favour of pluralism and calling for the removal of all amplification equipment from the mall to encourage this pluralism.

The A.L.P. City Council was viewed by the P.F.E. as vulnerable to pressure from the Party machine which appeared pregnable. The A.L.P. had for a number of years attempted to present itself as an alternative to the authoritarian, civil liberty denying National Party. Through its City Council it was now denying people the right to express themselves, and through the lobbying of its Lord Mayor would be party to the introduction of a most authoritarian State law and to the jailing of dissidents who refused to pay fines imposed. The possibility of causing tension within the Party, thus bringing pressure to bear on the Council, was highly probable.

The P.F.E. had few illusions about lobbying the National-Liberal State Government. Aware of its commitment to the antidemocratic permit system which had itself claimed 4,000 arrests costing millions of dollars in its enforcement - there was little hope placed or energy expended in appeals to the State Government. All members of parliament, however, were contacted with letters of argument and demand. There was a conscious attempt to attack the National Party suppression of civil liberties at its most basic myth - that of keeping the streets clean of Russian dupes, sympathisers and agents. The P.F.E., therefore, constantly pointed to the similarity between Queensland, Russian and Polish laws denying free speech and to the exemplary actions of the Polish Solidarity movement against such suppression. The economic links between Local Government Minister Russ Hinze and the Moscow Narodny Bank were also made constantly in speeches and campaign literature.

Within a week of the announcements by Russ Hinze (National Party), Roy Harvey (A.L.P.) and Glen Campbell-Ryder (City Heart Business Association) a new dimension to the proposed bill emerged. The proposed Queen St. Mall Bill would not only suppress freedom of expression in the Mall, "it would give police unprecedented powers to forcibly remove a person to a police station and hold that person indefinitely if they suspect that person has given a false name and address".

The new dimension of detention without arrest or charge was so overtly totalitarian, going beyond the traditional denial of free expression and breaking new ground for a police state, that it took most of the attention in the public consciousness. Whether this was a smokescreen to downplay the Bill's denial of free speech or certain sections of the public service, as later suggested in parliament (6), sincerely desired detention without charge is debateable.

The totalitarian nature of the detention dimension of the Bill drew opposition from traditionally conservative bodies.

"The president of the Queensland Bar Association, Mr. C.W. Pincus Q.C. yesterday described the amendment as "objectionable"."It introduces a concept of detention without arrest or even the formulation of a charge," he said. "It does not require the police officers suspicion that he has been given a false name or address be reasonably held and it allows the detention to go on 'while enquiries are made' in relation to the detained persons identity and addresses".

"Such inquiries could take hours or days. The opportunities for possible oppression are clear and the provision should not be enacted (7)".

In order to keep the issue of freedom of expression in the public mind during this period of intense public debate over the proposed Bill and to state our intentions of continuing non-violent non-cooperation in the eventuality of the Bill being passed, the P.F.E. decided on an organised course of action. "An Open Letter to Politicians" was sent to all State M.P.'s pointing out the issues involved, their "protected access to the major communication outlets (8)" and the threatened accessible means of communication, in the Mall. The letter ended with a call to action, "we are certain that you will come and actively defend these rights in the City Mall by speaking, leafleting and demonstrating. It is obviously crucial that such important residual powers of little people, the ordinary person in the street that you are so keen to serve should be defended by the moral courage that they expect of you. We await your action (9)".

"An Open Letter to the Police" was also produced pointing out the similarities between the proposed law and those of totalitarian regimes, reminding the police of their Nurembourg responsibilities and calling upon them not to enforce anti-democratic laws denying free expression. P.F.E. activists handed these letters to police and talked to them whenever the opportunity arose.

The P.F.E. sincerely believed that the law-enforcers - police and council officers - could be reached with our political ideas. The P.F.E. were aware that the morale of the police force had sunk during the 1977-79 "Right to March' campaign, with many police taking sickies or hanging back reluctant to arrest at demonstrations and also the case of Constable Michael Egan who refused to enforce the anti-march law and resigned on the spot at one demonstration. We were also aware of historic examples and the contemporary Polish Solidarity movement which had split police forces with their politics. There was a conscious decision not to present the police as automatons, as a focus for hate, but to attempt to communicate and challenge them at every opportunity. Although more hope for sympathetic non-cooperative action lay with rank and file police officers rather than the "Public Safety Response Team" and Special Branch, many saw this as an achievable goal.

The P.F.E. saw the A.L.P. as the most vulnerable power grouping and it was there that our pressure would be applied.

|

Mr. Bob Gibbs, A.L.P. Shadow Minister for Police and Justice, came down to the foyer to accept a copy of the petition (complete with 1000 signatures) to the A.L.P. and to make a public statement to the press in support of free expression and in opposition to the permit system,

" We believe that the forum at the present time, the Mall, is a place for the citizenry of Brisbane to be able to carry on orderly contact, and certainly we have no objection to people being able to express freedom of speech, to hand out pamphlets and for busking and anything else. Quite frankly we find it quite contemptible the statement in the paper this morning by the centre manager of the mall (Ryder) ... ..... we will fight this afternoon to protect the rights of people's freedom of speech in the city mall ...without a permit (10)"

By the end of the afternoon there had been a split in the government ranks over the detention issue and Mr. Hinze was forced to withdraw that dimension of the Bill. However, the amendments giving police the power of arrest of those people disobeying council ordinances were passed.

The day's action had revealed a significant split in the A.L.P. over free expression in the Mall, with Council and State representatives in an obvious conflict of policies.

The following day the conservative "Courier Mail" ran an editorial under the heading "No Place for Detention Law" referring to the proposed legislation as "containing an extension of police powers which should not be tolerated in a free democratic society (11)."

It was a healthy sign that at least some pillars of conservative Queensland would have to be moved before 'detention without charge' would gain a secure foothold.

The editorial, however, went on to state "Apart from the now deleted detention provisions in the mall and law courts legislation there is no argument about what the Bill seeks to do ...Spruikers can go elsewhere. The mall is for the tranquil enjoyment of the citizens of Brisbane (12)".

The Courier Mail editorial (31/3/83) was opposed to a concept of a "Free Speech Mall" but there was not to be a media consensus. In the sane paper political cartoonist Moir went beyond the detention issue to picture a large policeman in the mall shouting "FREE SPEECH IS A THREAT TO LIBERTY" to a small man handing cut leaflets (13)".

A most significant turnaround occurred in the "Sunday Mail" (3/4/83) in an article by conservative social commentator Sylvia Da Costa Roque who had described the "Committee of 50" demonstration as anti-social. She drew a comparison with repression in eastern bloc countries and concluded.."...So I've changed my mind. People can march for whatever they want and I'll never complain again. And I'd rather fight through a mall full of buskers, marchers and sidewalk orators than one devoid of anybody but squads of people wearing jackboots (14)"

Later that week journalist Janine Walker was to take up the major myths of the free speech opponents. Opening her article with a concern that, "the proposed extension of police powers of detention took a great deal of the public attention from the real question...". She took up the question of the purpose of the Mall

"Surely it is not some sort of super outdoors, mufti-purpose advertising space for the businesses on either side ...... At the moment, the average citizen using the mall are passive recipients of whatever form of promotion/entertainment the traders and the council sees fit to provide. All carefully monitored for quality, whatever that may mean ... We are already such a passive society - we watch the world pass by on television; passive observers of everything from sport to politics and the distinction is increasingly blurred. Now it seems that the Prime Minister in the mall is all right but Joe Bloggs from across the street who wants to tell the world about the dangers of nuclear war somehow doesn't measure up ... To suggest that these people might interfere with ethers going about the much more important business of shopping is both patronising and rude ... The edifying spectacle of a cocktail mixing competition in the pink rotunda just might, conceivably, keep some people out of the mall (15)".

Although she retreated to a social-democratic "onus-on-the-police-to-prove" position the article had attacked the basic mythology of our opposition. Some journalists with a limited amount of autonomy were beginning to wrestle with the major issues and principles involved. These cracks in the conservative media consensus were signs of opportunities to be exploited.

Amongst libertarian activists there was a critical disposition towards the media. In its essence part of the free expression campaign was a protest against the hegemony of the centralised, one-way forms of communication in our society that television, radio and the centralised press represent. These forms of communication - rather than street speaking, street-theatre, leafleting, marching et al. - are sanctioned by the state because they are easy to control and because the isolation in which the message is received encourages passivity. The myth of neutrality and objectivity of the media was never swallowed by P.F.E. who were aware of the media's role in maintaining the status quo by restricting the depth of discussion of political, social and economic issues. (A role) which is particularly significant in Australia where all the major media outlets except the A.B.C. are owned by one of the big three - Packer, Murdoch or Fairfax (16)". There was a conscious decision not to make the mistake of measuring the political success of our actions on the basis of media reports or non-reports - since this could lead to demoralisation and away from grassroots action.

"An Open Letter to Media Workers" was printed, mailed and handed personally to reporters, editors, cameramen and photographers. This letter pointed out the significant issues of suppression of expression, the hypocrisy of government and council, the need for the defence of cheap accessible forms of communication as well as the media's role in keeping reports of our arguments and activities superficial and sensational. The media was not to be ignored or flirted with but to be challenged - like everyone else - for its complicity in maintaining the permit system.

There was also use of talkback radio shows by P.F.E. activists during this period.

During this period P.F.E. experienced two encounters with the authoritarian left. Seeing the potential for an election issue over civil liberties that could work against the National-Liberal government, the "International Socialists" and other marxists formed the "Democratic Rights Organisation" calling all into a popular front and to a mass rally in the mall on Friday night May 27th. The P.F.E. rejected the invitation to dissolve into the D.R.O. because of the lack of their commitment to free expression for everyone, their view of street-speaking as merely a means to encourage class conflict, their commitment to electoral "Joh Must Go" politics, their refusal to attempt to split the police force with politics and what was seen as a counter-productive tactic of "rallying in the mall". A leaflet was produced examining the ideological basis for these differences.

"...Perhaps the most basic difference in the positions of these two is a philosophical one, that is, the question of how social change occurs and what is desirable change. The Democratic Rights Organisation are operating on the basis of a crude form of Marxism, this being that peoples' ideas cannot be changed but that society is divided into two, unchangeable, groups, these being the good guys (the working class, which has not yet captured the state in order to bring about a dictatorship of the proletariat because it is denied the right to organise politically) and the bad guys (the ruling class, consisting of those who own the means of production and those who serve the class interests of this group - police, military etc., who are continually launching attacks on the working class and its right to organise in order to contain their revolutionary fervour). From this perspective, what the aims of a civil liberties campaign should be is to change the "objective conditions" preventing the working class from becoming organised. What is important on the basis of this perspective is to defend the right for the working class to organise and not necessarily the right to free speech. The logical extension of the marxist position and often on the left, is similar to Mr. Bjelke Petersen's. That is, those who agree with us can have the right to speak and those who don't agree with us cannot have the right to speak. This mentality is a poor basis for a civil liberties campaign. An example of this is the International Socialists in Melbourne attempting to physically prevent an anti-union march - so much for the right to march! The alternative position to this is anarchism (of the libertarian communist tradition), the philosophy upon which the "People for Free Expression" operate. According to this perspective, the basic struggle is against authoritarianism. Anarchists take a position on civil liberties which opposes any attempt to restrict free speech. This leads to anticensorship and free speech campaigns as well as just the right to organise. Free speech is the principle by which anarchists will work in a free speech campaign, not just a tactical demand or catchy slogan.Ideas or Workers

A member of the Democratic Rights Organisation asserted that ideas are unimportant, they do not change society, it is the workers that change society. Anarchists claim that society changes when people wilfully act in the world. When people are confronted by ideas they accept them or reject them and act on that basis. Because of this, free speech, whether it is street speaking, marching, leafleting, picketing etc., is an important aspect of social change. Another member of D.R.O. said after soap-box speaking in the mall, that street-speaking was pointless and the only reason it was worth doing was to attract people to the next D.R.O. meeting. Anarchists reject this arid claim that street speaking is an effective political activity ................................

...... Although street speaking is so much different to being harangued through megaphones or p.a. systems, those who would bare street speaking would riot differentiate between the two. The proponents of a permit system fur political activity in the mall (who are now on the defensive for their position, because of the street-speaking campaign) would Lake great delight in a rally occurring because it would justify their claims that political activity in the mall is objectionable. Given the fact a campaign in the mall is already under way, it would be counter-productive to destroy this campaign by having a rally in the mall (17)".

The D.R.O. was to restrain itself from using amplification equipment at its rally, it soon collapsed as a popular front group and the "International Socialists" continue to soapbox speak in the mall on a weekly basis.

The second conflict with the authoritarian left occurred at the April Peace Rally. At the rally a group of pro-abortionists attacked the "Prolifers for Survival" contingent (P.S. is do anti-nuclear weapons/anti-abortion group) destroying leaflets and blocking their banner from view. Ironically, five of the P.S. people being denied free speech had recently served prison sentences at the hands of the Queensland government for speaking, marching and leafleting without permits. Disgusted by this denial of free speech Greg, a P.F.E. activist not in P.S. and who holds a pro-abortion position, approached the group of feminists and asked them to allow P.S. freedom of speech. Refused, he went up to the official (closed) platform and asked the Chairman if he could make a "special announcement". Mistaking Greg fur a peace bureaucrat the chairman gave him the microphone after asking for the crowds attention.

Greg described the situation, identified himself as pro-abortion and defended the right of "Prolifers for Survival" to put their position. He then handed the microphone to one of the women involved in the attack on the P.S. stall. She did not address the question of free speech but assured the audience that the P.S. leaflet was "crap" and accused P.S. of being a conspiracy to "stop people screwing". As Greg took the microphone to challenge the woman to actually address the question of free speech and defend their suppression of free speech, the chairman decided that the debate over the nature of the peace movement should come to an end and wrestled the microphone back. Greg attempted to address the crowd without amplification and was later physically assaulted. The effect on the "left" of our free speech campaign could be felt at the next peace rally where "Prolifers for Survival" set up a soapbox and leafleted without being censored. Those opposed to their anti-abortion position debated with them and carried a banner "Disarm a Prolifer ".

People for Free Expression had a few weeks grace between the time of the Bill being passed by Parliament and being signed by the Governor. It was a period of three to four weeks where we would be able to explain to people the issues involved and what lay behind the differing positions being voiced.

A street theatre was developed that embodied the contending forces soapbox, (cardboard cut-out) television, a street-speaker, the mall manager, a policeman and a politician and contained a scriptural malleability that changed with new events and developments. The theatre became a three dimensional mirror as the real-life mall manager, street-speakers and police hovered around it. Its thrust had the mall manager, a politician and policeman rejecting the humble soapbox, calling press conferences and extinguishing street-speakers from the mall. The theatre never failed to attract a large crowd who would be leafleted and then addressed by street-speakers.

|

The arrests had occurred less than 50 yards from the Hoyts Theatre where the award-winning film "Ghandi" extolled the virtues of civil disobedience and the struggle for human freedom. The irony was riot missed by libertarians who issued a pamphlet picturing Ghandi threatening, "I won't eat another thing until they let them speak in the Mall!". The leaflet took up these ironies as well as the demands and was distributed at intermission of the film for several weeks. During this period P.F.E. would meet on Monday nights and plan the weeks' activities.

On Thursday (12/5/83) lunchtime the street-theatre group took up the "guerrilla raid" strategy and performed unannounced in the Mall. Following the theatre, activists addressed the crowd and collected money for the P.F.E. bail fund (a couple of hundred dollars was raised in this way).

On Friday night (13/5/83) the street-theatre was under way when the Special Branch police moved in to give people directions to stop speaking. Actors responded by tying a gag around their mouth. All the libertarians in the crowd tied on gags and handed them out to enthusiastic onlookers. The gags were decorated with colorful "Queensland Made" stickers expropriated from the Department of Primary Industries earlier in the week. The stalemate was deafening - a silent movie of political repression - until a tug of war developed over the soapbox. A policeman picked up the box, our lawyer placed his hand on it and began a legal argument over property rights; an activist misread this as a sign "to defend the soapbox" and was arrested quite violently. Another activist who attempted to calm the police down was arrested. He went limp in protest, arid was dragged some 50 metres down the Mall making speeches all the while. Lurked in the police car the speeches continued. Four others were arrested for speaking. Bail money was collected and a crowd gathered in a solidarity picket outside the watch-house. All arrested were bailed out.

AL the next P.F.E. meeting (16/5/83) several people indicated they were willing to carry out civil disobedience in the Mall and a number of creative direct action proposals were suggested. It was decided that rather than sacrifice our energies arid resources in one big-hit mass arrest - as the D.R.O. were proposing - we would spin out the civil disobedience campaign as long as possible. An action was agreed on for the, next Friday night a "guerrilla street theatre" for Wednesday lunchtime, and a role-play for Thursday evening.

The theatre and speaking on Wednesday lunchtime drew an enthusiastic crowd, marry questions asked and generous donations made to the bail fund. Friday night (20/5/83) saw the Special Branch and Public Safety Response Team (18) gathered around where we usually spoke. The street theatre group began a decoy action up at the Albert St. end of the Mall attracting a crowd and drawing the police away from our usual gathering place. As the police moved away from the usual gathering place two libertarians chained a third to- a nearby tree. As the street theatre was winding down under police threats Drew Hutton - the anarchist chained to the tree began his speech. P.F.E. activists, the police arid the crowd that had gathered moved down to the tree. Gags and leaflets were handed out as Drew spoke. One libertarian was arrested for leafleting, another for "miming without a permit (19)" when he stopped leafleting arid put on -a gag, arid also a civil liberties lawyer on his way to a dinner engagement for attempting to engage police officers in a dialogue over their interpretation of the law. The speech went for 25 minutes with the crowd peaking at 2,000. Business-as-usual was derailed as people stopped consuming arid spontaneously participated in an unlawful assembly. AS Drew's chains were finally snipped arid he was lead away by Special Branch he yelled, "We must break these laws to remain committed to democracy. It is right to do so. We have nothing to lose but our chains!".

The D.R.O. had called for a mass rally in the Mall for the next Friday night (27/5/83). P.F.E. decided against joining the D.R.O. initiated activities because they did not support the principle of free expression for all. The P.F.E. decided to continue with its weekly strategy of civil disobedience. Leafleting of the Ghandi film and unannounced lunchtime speaking and street theatre continued. On Thursday (26/5/83) lunchtime, Special Branch officers appeared in the Mall but failed to act on the illegal street speaking and theatre. When Special Branch members were referred to by name one of the officers approached a P.F.E. activist and said, "If you dent mention us we won't bother you!". A strange offer that hinted a shift in police policy was occurring.

The P.F.E. plan for May 27th. was to go into the Mall at our usual time of 7.45 p.m. (as advertised on our leaflets), this would occur after the D.R.O. Rally at 6p.m. Two effigies were made, a blow up Russ Hinze (Minister for Local Government) doll and a woodcut General Jaruzelski (Polish communist dictator) statue. Both standing at 3 ft. these images would once again make the connection between the silencing of free expression both east and west and attack the National Party myth that they were the "free-worlders" and that we were the enemies of freedom, friends of Russia etc. These two figures would be placed on soapboxes with "questions" being asked (speeches made) from the crowd; the police would eventually remove (arrest) "Russ" and "the General". As they were being removed two P.F.E. activists would then risk arrest by making speeches against "their arrest" and in defence of ail peoples' - even authoritarians like Hinze and Jaruszelski - right to free expression.

When P.F.E. activists arrived in the Mall the D.R.O. had been speaking for a couple of hours with no trouble from the police. The Special Branch hint was correct, a shift in policy had been realised. There were no arrests. We celebrated with some anxiety-free theatre and speaking.

The strategy of creative acts of civil disobedience on a weekly basis had been effective. There was a number of other activists prepared for arrest in the weeks to come with a number of civilly disobedient acts in various stages of preparation (one anarchist household was left holding a coffin they had constructed for a funeral march for democracy).

Five days later (2/6/83) Tom Burns (A.L.P.) M.L.A., declared in the press that he was going to risk arrest exercising his free speech in the Mall;

LABOR TO DEFY LAW" The Australian Labor Party this morning will defy State Government legislation and stage a political function in Brisbane's Queen St. Mall.

The party will launch its Queensland heritage policy outside Her Majesty's Theatre for which a demolition application has been lodged, although it is intended to preserve the facade.

The policy will be unveiled by the Opposition Leader, Mr. Wright, and the Opposition spokesman on heritage matters Mr. Burns. .

Mr. Burns said last night he would not be deliberately setting out to flout the law but was entitled to free speech even if the Premier, Mr. Bjelke-Petersen, and his National Party did not believe in it.

"I will be launching this policy in front of a building that could have been saved if the Government had kept its promises years ago. Her Majesty's is something that should be saved."

"I am not looking for trouble but the cops can come and get me if they like."

The Police Minister, Mr. Glasson, said last night that police would not be doing anything about the launch.

As far as he was concerned, the Brisbane City Council was responsible for mall administration. If it did not see fit to do anything, he did not see why the police should be concerned (20)".

With the immediate battle having been won the P.F.E. decided to consolidate. We realised to win the Mall was to make street-speaking there an accepted part of Brisbane life. To do this we had to go beyond the relatively small anarchist and radical christian movements and convince other groups that it was in their own interest to begin to use the Mall as a forum for their ideas and campaigns. This was attempted in three ways;

These attempts to involve people and groups outside the anarchist movement largely failed. Except for the "International: Socialists" who continued to speak in the Mall on a weekly basis, there was little response. I will examine the reasons for this in detail later.

The P.F.E. also tried to consolidate by driving the wedge deeper into the A.L.P. ranks. We attempted this by writing a letter to all Queensland branches of the A.L.P. outlining the civil liberties issues involved, the A.L.P. City Council's role in suppressing free speech, our demands of enforcing A.L.P. policy in support of free speech and pointing out,

"The A.L.P. in Queensland will soon become a party to the Jailing of people who were arrested in May, 1983 in the Queen St. Mall. Some of those who will be jailed (for not paying fines incurred when convicted of exercising their right to express an opinion in public) were charged with breaching the city council's Mail ordinances (21)".

Over the next few months positive and supportive messages were received from rank and file members of the A.L.P.

|

The P.F.E. list of demands to the A.L.P. (with over 1,000 signatures) which had been handed to Lord Mayor Harvey on 29/3/83 and read as a petition to City Council had been requested by Special Branch, the council official approached had refused.

In a "Courier Mail" article on 23/6/83 entitled "POLICE ADMIT PETITION REQUEST", the acting Commissioner admitted to the request by Special Branch for a copy of the petition. He justified their actions by stating "it was the branch's responsibility to watch closely the activity's of suspected subversive and radical groups which could pose a threat to the community (23)".

The damage had obviously been done as the notion was generalised that signing a petition was enough to make one "suspect" in Queensland. The links between the denial of free speech, secret police dossiers and authoritarian government were being made in the public mind. The headlines of the "Sunday Mail" (26/6/83) read "BURN THOSE FILES" with a statement by Wright that a Labor Government would disband Special Branch and destroy its files on innocent people (24)". The conservative "Courier Mail's" editorial headed "A WATCH ON THE WATCHERS" began,

"The Queensland Police Force's Special Branch has an enthusiastic response to its responsibilities.So enthusiastic in fact, as to be disturbing. In a democracy, a citizen should be able to sign a petition seeking the change of a law without the fear of surveillance. By seeking the names of people who had signed a petition protesting against the Queen St. Mall legislation, the special branch exceeded its authority (25)".

The following day a feature article in "The Courier Mail" was critical of Special Branch's general operation and activities pointing out, "Apparently no one but the Police Commissioner knows how much the Special Branch costs the taxpayer each year, how many police officers man it, or precisely what information they collect on Queensland citizens (26)". The reporter spent 50% of his article on how difficult it was for him to gain information on the Special Branch.

The Special Branch - which had been the key government tool employed against P.F.E. activists in the Mall - was now publicly on the defensive suffering massive media blows to its credibility. To finish them off P.F.E. decided to run an anti-Special Branch theme to its first court case - arising from the May (Mall) arrests. The first court case involved John Nobody who had been arrested by a member of the Special Branch. P.F.E. called a "Lop the Branch" picket outside the magistrates court building where participants were encouraged "to come as your favourite secret police". On July 7th. people dressed in overcoats, hats and sunglasses with badges claiming to be from "ASIO", "CIA", "KGB", CHAOS", "Special Branch" and one man in a red dressing gown claiming to be "Cardinal Berni Moloney from the Vatican Secret Police" assembled outside the magistrate's court.

Following the court case in which John was convicted, P.F.E. activists assembled illegally in the Mall, illegal speeches about the petition issue were made and the petitions that had been handed to the State A.L.P. in March were burned.

Three other P.F.E. activists = Jim Dowling, Sean and Ciaron O'Reilly'- declared they would fight their court cases and refuse to pay any fines imposed. All the radical christians decided to defend themselves and approaches varied from defences on questions of law to an attempt to name the arresting officer as the defendant in breaking international laws and agreements protecting free speech. All were convicted and given time to pay.

In late June confirmation of victory arrived in a newspaper article entitled "POLICE, COUNCIL ROW OVER MALL" the police department, in effect, stated that they would not be enforcing the laws silencing political speeches in the Mall;

"A row has erupted between the Brisbane City Council and the Queensland Police Department over who should break up political activity in the Queen St. MallA police spokesman said the responsibility was with the council, which had authorised officers - "some with wider powers than police" - to handle such situations.

But a council spokesman said the police, who had the power to arrest, should break up political activity and were using the council as a scapegoat.

The police have decided that they will not let themselves "be embroiled in politically sensitive areas" and will turn a blind eye to any political speeches unless violence erupts or public and private property is being damaged.

Assistant Commissioner (Operations), Mr. Ron Redmond, said on Friday that all political speeches in the Mall were to be "supervised" by the council if required.

But the council accused the police of hypocrisy (26)

The P.F.E. recommitted itself to a period of consolidation following the court cases, attempts to make soapbox speaking in the Mall an accepted part of Brisbane life and to involve more groups. The businessmen and power brokers were to supply us with a public opportunity to attempt the first objective and the Hiroshima Day Rally the second objective.

Libertarian activists involved n a variety of struggles, had for years despaired about the undemocratic, centralised and boring manner in which rallies had been conducted in Brisbane (and most other places for that matter!). The modus operandi of one closed platform of pre-appointed speakers - usually A.L.P. sanctioned - behind the safety of microphones and huge speaking equipment. People who are called to the rally are forced to play the role of the passive audience as bureaucrats deliver much the same speeches as they gave last year.

Behind the microphone they stand unquestioned. If someone questions from the crowd they are branded "ego-maniacs", "wrecker" etc.. In previous years anarchists would attempt to "democratise" the rallies by trying to grab the microphone at some stage and put it to the crowd to vote on an open platform. On one occasion a banner which read "We're Bored! How About Open Platforms?" was held behind a closed platform at one rally. On reflection, these attempts would only lead to pushing and struggling for the microphone, and if successful would merely lead to 20 or more speakers with the majority of people still playing the passive audience role. We concluded that soapboxes were the instrument for the mass rally which could present a variety of opinions at the same time - where people could question and argue about the issues involved. For Hiroshima Day (August 6th.) 1983 libertarians organised Brisbane's first democratically structured rally. Anti-power grabbing groups anarchists, "Prolifers for Survival", "War Resisters League", "House of Freedom", "Catholic Worker Community", "Paddington Work Cooperatives", "Community Circus", "Children's Liberation Front") set up soapboxes, street theatre and stalls. Four soapboxes ran with questions firing from the crowds gathering and discussions breaking out between people who gathered. The soapbox had returned as a catalyst for self-activating rallies transforming a passive audience into communicating participants. When the bureaucratic peace organisations (A.L.P., Communist Party, Socialist Parties, Trade Union and Church bureaucrats) turned up an hour later to secure power by imposing an amplified closed platform the momentum was too strong to swamp. The rally was a great success for libertarian organisation.

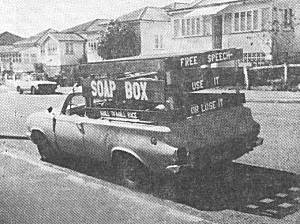

The opportunity to publicise the Mall as a free speech area was provided by a promotional stunt organised by the City Council, State Government and City Heart Business Association. The "Mall to Mall Race" - from Townsville Mall to Brisbane Mall - was an invention; to promote the Mall as a prime business area and as a monument to the administrations of Lord Mayor Harvey and Premier Petersen. The race would provide us with the means to celebrate (and entrench) our victory in the Mall, take the struggle for free expression outside the Mall and into the streets of the Queensland countryside and escalate our counter-cultural attack on conservative Queensland.

|

On the day of their departure the "Sunday Sun" ran a human interest story on "A Cop's Beat in the Mall" featuring a photograph of "The Neutron Bomb Minstrel Players" with the explanatory note, "Peaceful demonstrators in Queen St. Mall get on with the act without fear of being arrested (27)." The article confirmed a change in police behaviour and the Mall as safe territory for political activity.

Ciaron spoke in Townsville Mall on the two days preceding the race and on race day to those gathering at the starting line. Thousands of Townsville people lined the streets for the "event" and as the giant soapbox rolled up the main street Jim - behind the wheel - leafleted the crowd and Ciaron standing on top of the box addressed the captive audience. The speaking went on for about half a mile with a good response from the crowds before police moved in and "gave a lawful direction".

Over the following five days (28/8/83- 2/9/83) they spoke in Mackay, Rockhampton, Bundaberg, Maryborough, Gympie and Nambour.

On Friday (2/9/83), fifteen minutes after the official ending of the race, the giant soapbox limped into Queen St. It had suffered total destruction that morning 30 kms. north of Nambour and had been rebuilt. Anarchists had organised a "civic reception" for the soapbox with a gigantic (cardboard cutout) cup in the "Freedom Stakes" being presented to Jim and Ciaron by a tuxedoed anarchist mayor. Street theatre included a lap of honour of the Mall pursued by a policeman. A celebration of free expression - five hours of soapbox speaking - then followed. This celebration was occurring approximately one year after the "Committee of 50" opening of the Mall as a free speech zone. The variety of libertarians taking turns in speaking, reflected how many activists had been empowered in the instrument of street speaking.

Street-speaking continued on a weekly basis and six weeks later (3/10/83) Ciaron was picked up in West End for refusing to pay fines for the May arrests. He was taken to Boggo Rd. Jail for five days. The following week John and Jim were imprisoned. Sean was jailed in December.

During the imprisonment of John and Jim, P.F.E. gathered in the mall spoke and distributed an "Open Letter to Shop Owners"(28) and then occupied the city council chambers. In mid-November P.F.E. wound down and the weekly commitment to speaking on Friday nights ended. This concluded a successful year long campaign and ten months of weekly street speaking.

|

Libertarians were aware that the restrictions on free expression have their roots deep in the social, political and economic organisation of our society. The attack on these restrictions in the Mall was complemented by attempts to build a counter-culture and counter-institutions in the West End area. Activists involved in the "Committee of 50" and "People for Free Expression" were involved in a myriad of activities (29) that contributed to the building of community which in turn provided a springboard to attack the State with such creativity and continuity and also supported activists through attacks by the State (arrests, court cases, imprisonment, raids and general intimidation). Hitting the Mall on a Friday night became a clash between two communities, two cultures. A celebration of a community of spontaneity, creativity, and life embodied in street theatre, street-speaking and busking up against the rule of death, profit and uptight bureaucrats embodied in its sexist fashion parades, piped muzac and consumer hype. A visible sign of growth was in the number of libertarians confident in the art of street speaking as the campaign rolled on. Empowerment was visible.

The failure of the campaign was the failure to create a continual presence in the Mall that went beyond the limited resources of the anarchists and radical christians. It was a failure to achieve a significant response from other protest, ecology, human rights and peace groups to use the Mall. Besides the "International Socialists", Moonies and evangelical christians our call to "Use the Mall" went largely unheeded. I feel an examination of the reasons for this lack of response would hold valuable revelations concerning the contemporary protest movements.

The lack of response by the broader (peace, human rights, ecology and community) movement to the opening we had created for their ideas to flow was a sad reflection of their political priorities. Our street theatre could have been amended to take in the character of the "1980's activist"! The theatre ran where the soapbox was offered to the mall-manager, the politician and the policeman to argue their positions and defend their actions, all the characters reject the street speaker's offer and address the audience through the (cardboard cutout) television. This, in real terms, was the response of the broader movement in Brisbane. It is an attitude of mass media infatuation which is reflected in the political activity they conduct. Rallies are called, pickets are staged, marches are marched not to communicate with "live people" on the street but as a means to buy time on television and space in the centralised press. Their rallies are scripted and stage-managed - now often chaired by media "poisonalities"- for efficient television presentation. A presentable consensus is maintained by a closed platform at the cost of the real people who have turned up communicating with each other. A decentralised rally based on the self activity of the ralliers won't sell on T.V.

The 1980's activist "go for the box" (T.V.) because they are unwilling to play their limited inch by inch, step by step, consciousness by consciousness role we will all have to play if real change is to be realised. If we are to avoid global death by nuclear bang or ecological whimper. In the search for the shortcut the 1980's activist want to wave the magic media wand and communicate to the masses at the same time. The have rejected the soapbox as inefficient. They reject face-to-ace communicating and choose the "one invades: thousands absorb" mediums. In this they have rejected a catalyst for debate and conversion and chosen a one-way medium that meets and leaves the receiver of the message in a state of passivity and isolation. They have chosen the medium of the culture whose excesses they oppose. But in the most basic sense they have confused building a mass movement with projecting their movements in amass way.

The ramifications of this choice are examined thoroughly in a work by Jerry Mander entitled "Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television". Mander was the President of a Californian advertising firm who was politicised by the civil rights and peace movements of the 1960's. His concerns turned to the media particularly how to influence the press to carry stories emphasising issues rather than disruptions or violence. Mander's agency was hired by the Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth and he later went on to create a foundation funded, non-profit advertising and public relations office called Public Interest Communications. P.I.C. was devoted solely to working for community organisations excluded from the media. He soon came to the conclusion that quantitatively it was an area in which there was just no chance of competition:

"My evening clients, speaking of social issues, needed to organise hundreds of people into confrontative acts which could get them extensive, if often unfavourable, coverage. Or, if they chose less confrontative routes, they could spend weeks of time and all their hard-won nickels and dimes to organise press information programs which would, at their most successful, net them a few inches in the back, of the newspaper.Meanwhile, any of my daytime clients, speaking for commercial purposes, could and did buy advertising space and time worth tens of thousands of dollars. Then they would do it again the following week.

I already knew that, in America, all advertisers spent more than $25 billion a year to disseminate their information. Now, however, I was beginning to pay attention to an obvious, yet little noticed, aspect of this situation. Virtually all of the $25 billion was being spent by people who already had a great deal of money. These were the only people who could afford to pay $30,000 for one page of advertising in "Time" ($54,000 by 1977) or $50,000 for one minute of prime time television ($125,000 by 1977). Ordinary people and small businesses, even those which are successful by most standards, can rarely afford any advertising beyond the want ads, or small local retail displays. Only the very rich buy national advertising. And they do this to become richer. What other motive could they possibly have?

A.J. Liebling once said "Freedom of the Press is limited to those who own one." I was learning that access to the press was similarly distorted by the possession of wealth. People with money had a 25-billion-to-nearly-zero advantage over people without money. The rich could simply buy access to the public mind while the not-rich had to seek more circuitous routes (1)".

He later came to the conclusion that qualitatively it wasn't even worth the effort of capturing television time. The communication and experience of television was politically counter-productive for the movement. It created and encouraged a sort of one-dimensional thinking that was politically crippling;

"The Vietnam War was halted, but the arms race and military aid to right-wing regimes advanced. Nixon was thrown out, but government reform came down to a lame Senate ethics bill. Unemployment was growing and welfare lines with it, yet in the end economic reform measures always seemed to hurt the very segments of the population they purported to help while the rich got richer.One young activist told me, we seem to be running on a treadmill; as we advance, we are always in the same place."

Every issue had to be fought as though it was the first one. People seemed unable to connect one issue to another, to find common threads in, say, a struggle against high-rise office buildings and nuclear power plants and colonial wars. Specific victories were possible, but overall understanding of the forces that were moving society seemed to be diminishing.

People's minds seemed to be running in dogged, one-dimensional channels which reminded me of the freeways, office buildings and suburbs that were the physical manifestations of the same period. Could one be affecting the other? Could life within these new forms of physical confinement produce mental confinement? For the first time I began to think this might be possible (2)".

Mander realised that television was creating a culture that has substituted secondary and mediated versions of experience for direct experience of the world. "Interpretations and representations of the world were being accepted as experience, and the difference between the two was obscure to most of us (3)". The people at the other end of the transmissions were only experiencing "sitting in a darkened room, staring at flickering light, ingesting images which had been edited, cut, rearranged, sped up, slowed down, and confined in a hundred ways (4)".

It became clear to Mander that, "A new muddiness of mind was developing. People's patterns of discernment, discrimination and understanding were taking a dive. They didn't seem able to make distinctions between information which was pre-processed and then filtered through a machine and that which came to them whole, by actual experience (5)". He began to realise the consequences of the qualitative nature of television communication for his work in the ecology movement;

"Slowly I began to realise how the ubiquitousness of television, combined with a general failure to understand what it did to information, might effect the political work we were doing. If people were believing that an image of nature was equal to or even similar to the experience of nature, and were therefore satisfied enough with the image that they did not seek out the real experience, than nature was in a lot bigger trouble than anyone realised (6)".

It was Mander's witnessing of the destructive effect of television on the protest movement that moved him to his abolitionist stance. The failure of the Brisbane protest groups to respond to the opening in the Mall can be seen in the following context;

'My own feelings about the effects of television began to progress as I observed its effects on community groups and movement people who, believing in its neutrality, sought to use it.I watched and participated as they changed their organisations' commitments from community organising, legal reform processes or other forms of evolutionary change to focus upon television.

Educational work was sacrificed to public relations work. The goal became less to communicate with individuals, governments or communities than to influence media. Actions began to be chosen less for their educational value or political content than for their ability to attract television cameras. Dealing directly with bureaucracies or corporations was frustrating and fruitless. Dealing with communities was slow. Everyone spoke of immediate victory.

A hierarchy of press-orientated actions developed. Rallies attracted more coverage than press conferences. Marches more than rallies. Sit-ins more than marches. Violence more than sit-ins.

A theory developed: Accelerate the drama of each successive action to sustain the same level of coverage. Television somehow demanded that. As the stakes rose, the pressure mounted to create ever more outrageous actions.

The movements of the 1960's had become totally media based by the 1970's. The most radical elements were up to the challenges of the theory of accelerated action. They "advanced" to kidnappings, hijackings and bombings. The sole purpose of these actions was often no more than media exposure.

Sensing that television was now the country's main transmitter of reality, individuals began to take personal action to affect it.

A young Chicano man hijacked a plane to obtain a five-minute T.V. interview about the mistreatment of his people.

A young man in Sacramento took some bank employees hostage so that a T.V. news team would report that neither he nor his father could get a job..

Lynette Fromme shot at President Ford, she said, so the media would warn big business to cease destroying the planet.

The S.L.A. kidnapping of a newspaper heiress signalled the final stage of abstraction. It exhibited a warped genius in that it allowed the S.L.A. to demand successfully that their communiques would be published unedited.

However, because it owed its whole life to the media, existing nowhere else, the S.L.A. was subject to cancellation at any time, and it was cancelled most thoroughly, like a series with slipping ratings getting the axe.

Less radical elements did not suffer the S.L.A.'s dramatic demise, but the cycle of fast rise/fast fall was similar for many. Ralph Nader bloomed in the media and then became tiresome. The ecology movement fitting the holocaust model of T.V. news, burst upon the scene and then declined. Watergate excited expectations of government reform, but then it was old news.

Once the U.S. was out of Vietnam, the once hot antiwar movement was off the tube. A few years later Jimmy Carter was able to appoint some of the architects of the war to high positions in government. It was as though the war hadn't happened, or was merely another action-packed drama, replaced by next season's schedule, with the same actors playing new, equally believable roles.

Meanwhile those seriously committed Movement people of the 1960's who were not willing to go on to terrorism began dropping out, moving to farms in Vermont and Oregon. Or, I know many who have done this, they got jobs writing television serials. They justified this with the explanation that they were still reaching "the people" with an occasional revolutionary message, fitted ingeniously into the dialogue.

"The people", however, were as they had been for years, sitting home in their living rooms, staring at blue light, their minds filled with T.V. images. One movement became the same as the next; one media action merged with the fictional program that followed; one revolutionary line was erased by the next commercial leading to a new level of withdrawal, unconcern and stasis (7).

As pacifists would no more use the gun in an effort to achieve their objectives those who wish to create a counterculture based on self-activity, participation, self-management and direct democracy have no use for television. Stand on one and see if it makes a good soapbox!

Ciaron O'Reilly

Campaign History

Epilogue

Ciaron O'Reilly identifies himself as a christian anarchist, and as a member of the Catholic Worker Movement, refer: